In 1992, the Choreographer Bill T. Jones lost his partner Arnie Zane to HIV/AIDS. Shortly thereafter, as he moved through his own grief and still in the crisis days of the AIDS epidemic (and HIV positive himself) he initiated a series of what he called Survival Workshops. He began working with individuals who had life-threatening illnesses who wished to be a part of a hybrid performance called

In 1992, the Choreographer Bill T. Jones lost his partner Arnie Zane to HIV/AIDS. Shortly thereafter, as he moved through his own grief and still in the crisis days of the AIDS epidemic (and HIV positive himself) he initiated a series of what he called Survival Workshops. He began working with individuals who had life-threatening illnesses who wished to be a part of a hybrid performance called  Still/Here. The project premiered in 1994 after Jones collected narrative material and stories from over 100 participants across the country. The resulting piece was a poetic, frank, in-your-face manifesto about the power of survival and community and the power of art. I often ask the rhetorical question, “what can art do?” to address historically fraught moments, or personal trauma. Still/Here did all that and more as it turned the collective grief of the moment into a joyous, radical stand against complacency through dance, song, video, music, and spoken word.

Still/Here. The project premiered in 1994 after Jones collected narrative material and stories from over 100 participants across the country. The resulting piece was a poetic, frank, in-your-face manifesto about the power of survival and community and the power of art. I often ask the rhetorical question, “what can art do?” to address historically fraught moments, or personal trauma. Still/Here did all that and more as it turned the collective grief of the moment into a joyous, radical stand against complacency through dance, song, video, music, and spoken word.

We are still here; artists and educators in need of an audience to feel a part of a collective feedback loop. We are teaching and creating in solitary rooms, our process sanitized and stripped of human connection. It’s exhausting. I often write and talk about Susan Sontag, in particular her writing about illness. In Regarding the Pain of Others, she wrote:

It is intolerable to have one’s own sufferings twinned with anybody else’s.

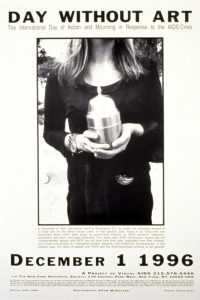

What resonates to me about that sentence is that our own suffering or grief or exhaustion is local. It is particular to each of us and felt in the context of our own life experience. We cannot really experience the suffering of everyone everywhere, but we can be empathetic, even while experiencing our own particular and individual pain. Pain or loneliness or fear are not things that one can be talked out of. And as we experience this moment of crisis together, though separated and isolated, I’m also thinking about the critic Michael Brenson’s mantra that “artists are persons.” Speaking about his involvement with New York’s Creative Time and the activist group Visual AIDS’ project called A Day Without Art in 1996, he asked rhetorically:

How do you get people to understand that artists are real working people? That artists are interesting people, that artists are part of the community just like you and me?

For Brenson, artists are resilient, thoughtful, complicated people, who suffer, grieve, participate in the cultures around them and can offer insight into a range of experience. In his book, Acts of Engagement, he tells a story about how, as funding for the arts (especially the National Endowment for the Arts) shrank throughout the 1980’s, artists pivoted to new ways of working and new models of community engagement, which in turn, produced new ways of thinking about art.

For Brenson, artists are resilient, thoughtful, complicated people, who suffer, grieve, participate in the cultures around them and can offer insight into a range of experience. In his book, Acts of Engagement, he tells a story about how, as funding for the arts (especially the National Endowment for the Arts) shrank throughout the 1980’s, artists pivoted to new ways of working and new models of community engagement, which in turn, produced new ways of thinking about art.

The HIV/AIDS crisis is certainly not the same as what we are currently experiencing, though out of that trauma came extraordinary art and activism. In such times, the world around us, and all the things in it, glisten with meaning.

I have been looking at a piece by the artist Zoe Leonard, who was a vocal AIDS activist in the 1980’s. The sculpture Strange Fruit (for David) honors the memory of the artist David Wojnarowicz and is made with 302 pieces of dried and rotting fruit, some sewn together and left to decompose on the floor of wherever they are being exhibited.

I have been looking at a piece by the artist Zoe Leonard, who was a vocal AIDS activist in the 1980’s. The sculpture Strange Fruit (for David) honors the memory of the artist David Wojnarowicz and is made with 302 pieces of dried and rotting fruit, some sewn together and left to decompose on the floor of wherever they are being exhibited.  The piece has been described as a mourning ritual that suggests a new community forged in the crucible of grief. It is ultimately a work about the ability of artists to rebound and to form even stronger communities out of trauma as we will, as we always do.

The piece has been described as a mourning ritual that suggests a new community forged in the crucible of grief. It is ultimately a work about the ability of artists to rebound and to form even stronger communities out of trauma as we will, as we always do.

Douglas Rosenberg

Chair, UW-Madison Art Department