Works which demand to be ‘seen and read’ absorb the dialogues and refusals between visual and written communication, and explicitly ask for us to reappraise how we consume literature and art.

—Elizabeth Benjamin and Sophie Corser, Literature and Art: Conversations and Collaborations

I have been thinking a lot about the deep and meaningful connection between visual art and literature. The work of our students and, indeed, the work of many artists beyond academia often have connective tissue in whose DNA are allusions to the literary. I am thinking particularly of work by Rebecca Horn, Joseph Beuys, and others; work that is epic, poetic, operatic, sacred, and makes us feel and respond to its sense of significance. I find that work by artists with such literary connotations often moves me deeply.

By hailing or signifying their literary and cinematic colleagues, artists in such a mode are acknowledging that art is connected beyond the image or object, and obligate the viewer to read a work of art far beyond its formal qualities. We, the viewer, need to search for and consider its evidentiary nature; to whom or what is it pointing or quoting, and what are the clues that tell us so?

In Rebecca Horn’s work, objects and installations speak to loneliness, and a sort of comic absurdity that she has noted is inspired by Samuel Beckett and Buster Keaton. In her film, Buster’s Bedroom, often screened within her museum exhibitions, Horn creates a world where surreal characters populate a sanatorium, alienated and cut off from the reality of the “real world,” much as Horn herself was at an earlier point in her own life.

In Rebecca Horn’s work, objects and installations speak to loneliness, and a sort of comic absurdity that she has noted is inspired by Samuel Beckett and Buster Keaton. In her film, Buster’s Bedroom, often screened within her museum exhibitions, Horn creates a world where surreal characters populate a sanatorium, alienated and cut off from the reality of the “real world,” much as Horn herself was at an earlier point in her own life.  Sculptural pieces inspired by or alluding directly to the theater artist Samuel Beckett convey a similar feeling of ennui or dislocation.

Sculptural pieces inspired by or alluding directly to the theater artist Samuel Beckett convey a similar feeling of ennui or dislocation.

Einstein on the Beach, the epic opera collaboration between Robert Wilson and Phillip Glass which premiered in 1976, takes as its starting point an old photograph of Albert Einstein, indeed strolling on the beach. While the opera is not a narrative about Einstein’s life, Glass notes that, “practically every image comes from Einstein’s life or ideas: trains, spaceships, clocks.”  The recurring image on-stage of an Einstein character who plays the violin referenced his amateur’s love of the instrument.

The recurring image on-stage of an Einstein character who plays the violin referenced his amateur’s love of the instrument.

Robert Rauschenberg’s Dante Illustrations, made between 1958-1960, was comprised of thirty-four drawings, one for each Canto or section, of Dante’s poem The Inferno, written between 1308–1321.  In the series, Rauschenberg famously created a contemporary context for the epic poem by inserting political figures such as John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon. There are allusions to the Civil Rights movement and anti-Communist paranoia as well as the sexual politics of the era, all appropriated from print media and collaged into what he came to call combines.

In the series, Rauschenberg famously created a contemporary context for the epic poem by inserting political figures such as John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon. There are allusions to the Civil Rights movement and anti-Communist paranoia as well as the sexual politics of the era, all appropriated from print media and collaged into what he came to call combines.

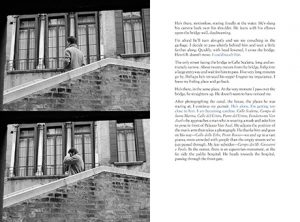

The artist Sophie Calle’s novel Suite Vénitienne/Please Follow Me, published in 1983, is a diaristic collection of photos and text created as she surreptitiously follows a man known only Henri B. from Paris to Venice over the duration of twelve days. Here, Calle’s work, which includes black and white photos that often stand alone as works of art, appropriates literature itself as a source for a work that blurs the boundaries between text and the image.

The artist Sophie Calle’s novel Suite Vénitienne/Please Follow Me, published in 1983, is a diaristic collection of photos and text created as she surreptitiously follows a man known only Henri B. from Paris to Venice over the duration of twelve days. Here, Calle’s work, which includes black and white photos that often stand alone as works of art, appropriates literature itself as a source for a work that blurs the boundaries between text and the image.

Douglas Rosenberg

Chair, UW-Madison Art Department