Curiosity is a radical act. To be a curious explorer of artistic and creative possibility, to be intellectually curious in the face of any status quo, effectively insures a life of constant questioning; like seeing the world as an early modern Cubist painting, always rotating the form, turning it around to see the other side of a question or an object. Such curiosity creates outliers in both art and in life. The kind of curiosity I am alluding to is not the curiosity that draws us to the most quotidian aspects of pop culture, or to simply linger while making a choice between the known and the unknown, to wonder, what if…but rather the curiosity that draws us to read history, to engage in the politics of our era, to think deeply about where we sit in the most contested ideas of our own time from issues of race and gender to the kind of inequities that plague and permeate many aspects of contemporary life.

Curiosity is a radical act. To be a curious explorer of artistic and creative possibility, to be intellectually curious in the face of any status quo, effectively insures a life of constant questioning; like seeing the world as an early modern Cubist painting, always rotating the form, turning it around to see the other side of a question or an object. Such curiosity creates outliers in both art and in life. The kind of curiosity I am alluding to is not the curiosity that draws us to the most quotidian aspects of pop culture, or to simply linger while making a choice between the known and the unknown, to wonder, what if…but rather the curiosity that draws us to read history, to engage in the politics of our era, to think deeply about where we sit in the most contested ideas of our own time from issues of race and gender to the kind of inequities that plague and permeate many aspects of contemporary life.

As the critic Michael Brenson has noted, “artists are people”, and people, especially those engaged with the purposes of making contemporary art, have the capacity for radical curiosity in the face of creative problem solving. If art is about perpetual problem solving (which I believe it is) and social engagement (which I also believe it is in the moment we live in), what part might curiosity play in pushing art toward a new model of engagement, one that breaks with tradition and fully engages with the generational shift toward new models generally.

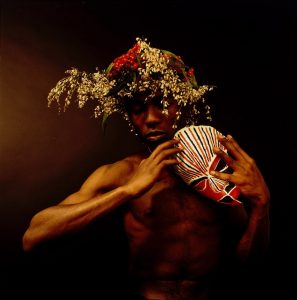

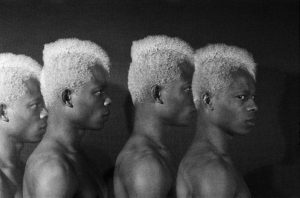

I’ve been looking at the work of the late Nigerian-born photographer  Romiti Fani-Kayode. While researching artists whose work explore masculinity in general, I was reminded of his seminal work photographing men throughout the 1980’s, until his death from complications due to AIDS in 1989 at the age of 34. While sometimes compared to Robert Mappelthorpe, as a consequence of both the era and his subject matter, Fani-Kayode’s curiosity led him to create “images that exalt queer black desire, call attention to the politics of race and representation, and explore notions of cultural identity and difference.”

Romiti Fani-Kayode. While researching artists whose work explore masculinity in general, I was reminded of his seminal work photographing men throughout the 1980’s, until his death from complications due to AIDS in 1989 at the age of 34. While sometimes compared to Robert Mappelthorpe, as a consequence of both the era and his subject matter, Fani-Kayode’s curiosity led him to create “images that exalt queer black desire, call attention to the politics of race and representation, and explore notions of cultural identity and difference.”

Such curiosity is the generative impulse that leads to research. In other words, curiosity leads us to wonder and to think and ultimately to do, to follow such impulses about the self or about others, to their logical conclusions, which for artists, may lie in the creation of images, actions or objects.

Such curiosity is the generative impulse that leads to research. In other words, curiosity leads us to wonder and to think and ultimately to do, to follow such impulses about the self or about others, to their logical conclusions, which for artists, may lie in the creation of images, actions or objects.

During the Nigerian Civil War, in 1966, at eleven-years-old, Fani-Kayode moved with his family to Brighton, England, and later to the United States to study at Georgetown University and at the Pratt Institute, where he earned an MFA in 1983. The peripatetic artist finally returned to England to pursue photography. Speaking about his own work, he noted:

On three counts I am an outsider: in matters of sexuality; in terms of geographical and cultural dislocation; and in the sense of not having become the sort of respectably married professional my parents might have hoped for.

As Fani-Kayode’s curiosity led him to turn to his cultural traditions, his sense of self and his empathy for others in his art-making practice, he left an archive that still resonates and in turn, becomes the object of the curiosity of others as we ask similar questions about ourselves.

As Fani-Kayode’s curiosity led him to turn to his cultural traditions, his sense of self and his empathy for others in his art-making practice, he left an archive that still resonates and in turn, becomes the object of the curiosity of others as we ask similar questions about ourselves.

Douglas Rosenberg

Chair, UW-Madison Art Department