Whatever art is, it is no longer something primarily to be looked at. Stared at, perhaps, but not primarily looked at. What, in view of this, is a post-historical museum to do, or to be?

-After the End of Art Contemporary Art and the Pale of History, 1996 by Arthur Danto

Living in the art world at this point in history is similar to what I would imagine living at an anthropological dig might be like; the constant surprise of the new, of heretofore unimagined methods of art-making made visible via excavation and careful indexing. Subsequent to Arthur Danto’s proclamation about the end of art, art is in the process of reimagining itself through the lens of 21st century culture. The practice of art and its methods of circulation are evolving to meet the possibilities of inclusive citizenship and material egalitarianism, moving well beyond the simply optical apprehension of shape, color, and form (as Danto alluded to), and toward a model that is, at times, quietly radical in its reframing of our very perception of the nature of art writ large.

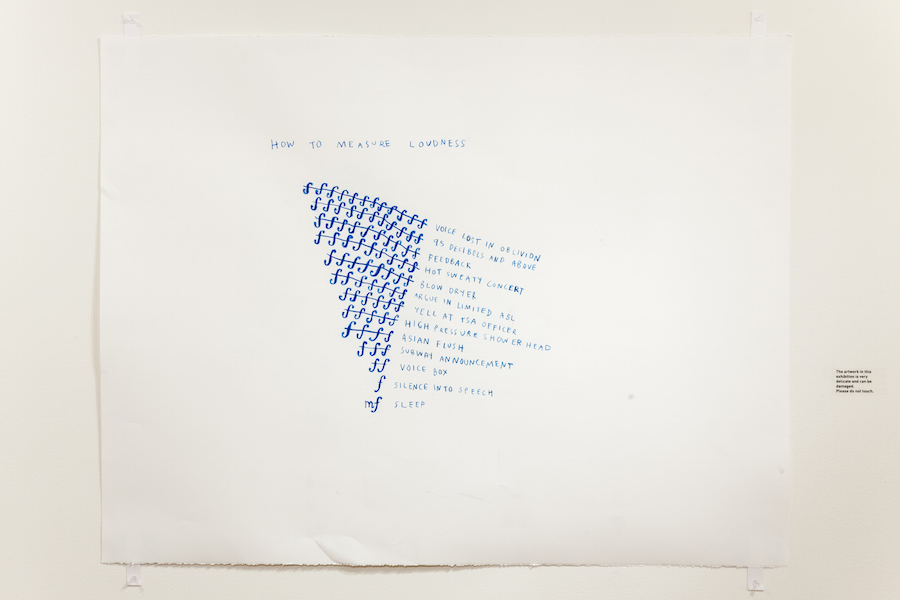

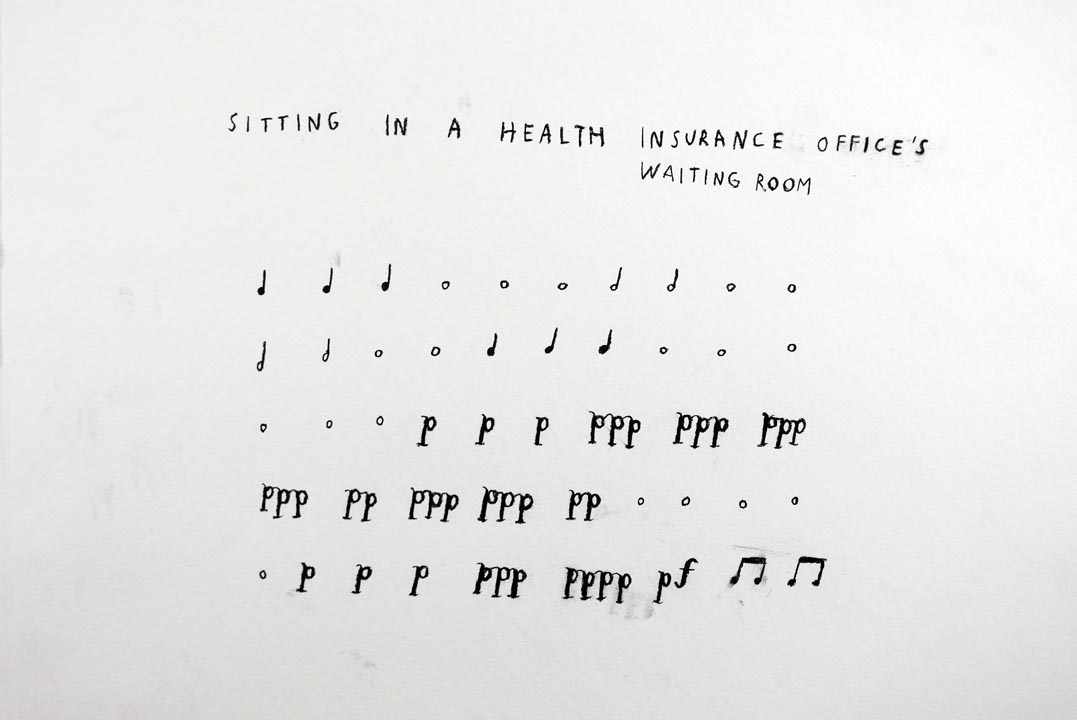

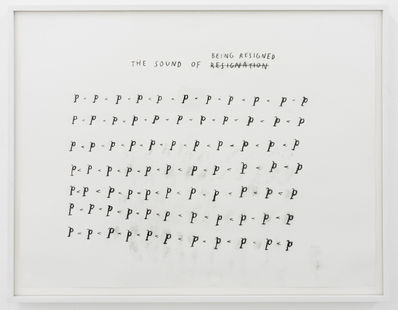

I’ve been intrigued by the work of Christine Sun Kim recently.Kim is an artist who works with visual art, performance and composition, using music and sign language as a part of her tool kit. Kim was born deaf and much of her work expresses her particular, almost synesthetic experience. Speaking about the methods by which she makes her drawings, which often allude to the structures of American Sign Language, Kim notes,

No interpreter is the same, no personality is the same, no voice is the same. I have all different voices for specific situations — a blue voice for fancy talks, a purple voice for social settings, an orange voice for conferences, a red voice for therapy sessions and so on. Putting all my voices together looks like a rainbow … and that would be my ideal voice.

Kim’s description of the process of translation and its relationship to color, is very similar to the way we understand synesthesia as a condition in which one sense such as taste, is simultaneously perceived as if by one or more additional senses. In the experience of synesthesia one may perceive letters, shapes, numbers or people’s names with sensory perceptions such as flavor smell or color.  Kim’s work actively questions the dominant understanding of “art” as politically fraught, overwhelming the possibilities of experiences by the minority deaf community, noting, “In deaf culture movement is equivalent to sound.”

Kim’s work actively questions the dominant understanding of “art” as politically fraught, overwhelming the possibilities of experiences by the minority deaf community, noting, “In deaf culture movement is equivalent to sound.”

People in the hearing world experience movement optically, as a stimulus that is framed by vision. Pushing back at early modern ideas about art as a specifically optical experience, Kim “reclaims ownership of sound” as an integral component of her art practice.  She likens sound to money, power, and control; a kind of social currency, that she is, to a certain extent, unable to access. American minimalist composers such as Steven Reich, Terry Riley and La Monte Young, for instance, used sound as an extension of the Western music tradition filtered through a number of theoretical framings including repetition and austere, glacial and evolutionary durational changes. Their work tended to capture the attention of listeners and, over time, sonically move them into an altered state of perception. Kim’s work is predicated on her experience of the absence of sound, or perhaps her acknowledgement of the overwhelming tyranny that sound imposes on non-hearing individuals.

She likens sound to money, power, and control; a kind of social currency, that she is, to a certain extent, unable to access. American minimalist composers such as Steven Reich, Terry Riley and La Monte Young, for instance, used sound as an extension of the Western music tradition filtered through a number of theoretical framings including repetition and austere, glacial and evolutionary durational changes. Their work tended to capture the attention of listeners and, over time, sonically move them into an altered state of perception. Kim’s work is predicated on her experience of the absence of sound, or perhaps her acknowledgement of the overwhelming tyranny that sound imposes on non-hearing individuals.

In Kim’s large-scale drawing project created for the 2019 Whitney Biennial, the artist reifies the physical gesture of the sign for future into two large, thick arcs of black pigment.The resulting piece Too Much Future, hanging in public space adjacent to New York’s High Line, renders the four dimensional act of signing into a kind of two dimensional musical or rhythmic notation, dwarfing the text that hovers above it. Thus we, the interpreters of the piece, are nudged into the experience of synesthesia and an involuntary sense of empathy for Kim’s own experience of the world.

Douglas Rosenberg

Chair, UW-Madison Art Department