My garden is full of sunflowers right now. None of them were planted by me, yet, there they are; a kind of crazy incursion of self-propagated second generation immigrant flowers set into motion by a crop planted and harvested last year. I did plant sunflowers again this year in an entirely different place in my garden and they did not thrive. Instead, the ones that found their way into being through persistence of purpose have staked out territory directly in the paths between my carefully cultivated beds; disruptors of the most beautiful kind. While not entirely welcome in the space they have squatted, their strange and effusive presence dares removal and their peculiar beauty, low slung and bountiful, defiantly commands the space.

My garden is full of sunflowers right now. None of them were planted by me, yet, there they are; a kind of crazy incursion of self-propagated second generation immigrant flowers set into motion by a crop planted and harvested last year. I did plant sunflowers again this year in an entirely different place in my garden and they did not thrive. Instead, the ones that found their way into being through persistence of purpose have staked out territory directly in the paths between my carefully cultivated beds; disruptors of the most beautiful kind. While not entirely welcome in the space they have squatted, their strange and effusive presence dares removal and their peculiar beauty, low slung and bountiful, defiantly commands the space.

As a gardener and an artist, it is hard not to see the world in terms of overlapping metaphor. Gardens are a partnership between humanity and nature in which the two coexist with the implicit understanding that opposing forces keep one another in check and on track. The garden ignored quickly becomes a wilderness. Artists manage material, imposing a sense of order (or disorder) to it to create some sort of new understanding of the world (humanity). Artwork is contingent on the attention of a public and it too is a fragile concern; ignored it also withers.

We are synergistic. Nature imposes itself on humanity and humanity, likewise, imposes itself on the natural world. In his book Emerson’s Nonlinear Nature, Christopher J. Wodolph looks at the philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson’s ideas about seeing and the natural world, its sense of order and form, and his poetic observations on the nonlinearity the contingency of experience. Wodolph notes:

All of nature, including humanity, participates in the metamorphosis of form. Emerson places repeated emphasis on Nature’s “flowing law,” the Aristotelian idea that forms are not static but continually changing according to fixed mechanisms of metamorphosis. All of nature, including humanity, participates in this metamorphosis of form. Likewise, in the essay “Nature,” the natural world “publishes itself… through transformation on transformation to the highest symmetries, arriving at consummate results without a shock or a leap.”

These are observations that might be equally pertinent to either my garden or a work of art. The sunflowers mentioned above were most certainly “published” by nature, a product of improvisation, process, and chance. And what is art practice generally, if not about the metamorphosis of form, of ideas, of process, and of action?

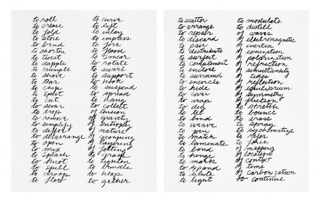

I was thinking about all of the above while recently perusing the artist Richard Serra’s Verb List Compilation: Actions to Relate to Oneself [1967-1968]. Written by Serra not as a work of art per se, rather as a set of directives apropos of the minimalist and interdisciplinary milieu of which he was a member. The list is an aspirational mantra. If read out loud it verbalizes and suggests an action; performed, it concretizes that action. Serra’s list imagines the process of making while posing the need to make or do, in other words “publishing” the object or gesture.

I was thinking about all of the above while recently perusing the artist Richard Serra’s Verb List Compilation: Actions to Relate to Oneself [1967-1968]. Written by Serra not as a work of art per se, rather as a set of directives apropos of the minimalist and interdisciplinary milieu of which he was a member. The list is an aspirational mantra. If read out loud it verbalizes and suggests an action; performed, it concretizes that action. Serra’s list imagines the process of making while posing the need to make or do, in other words “publishing” the object or gesture.

In writing about Emerson, Wodolph observes his ideas about the “developmental variety and variation” in nature and its overlap with the “fixed and immutable principles reflected in individual objects.” We might consider the same when speaking about works of art or visual culture in general; that they are all of a piece and it rests on the ones who observe to articulate the multiple possibilities of experience each may suggest.

Douglas Rosenberg

Chair, UW-Madison Art Department