In a short book, The Gift, written in 1966 by the French sociologist Marcel Mauss, the author distinguishes the numerous differences between historically understood gift economies; in which interactions are almost always reciprocal and more often than not used to build a kind of social solidarity. His book became a foundational text for social theorists engaged in scholarship surrounding gift exchange and the systems of such transactions. What is most interesting about The Gift is how it de-mythologizes the idea that the giving of gifts is inherently selfless. Rather, a gift may be made to further a larger social or personal concern, while still enhancing the experience recipient of the gift.

In a short book, The Gift, written in 1966 by the French sociologist Marcel Mauss, the author distinguishes the numerous differences between historically understood gift economies; in which interactions are almost always reciprocal and more often than not used to build a kind of social solidarity. His book became a foundational text for social theorists engaged in scholarship surrounding gift exchange and the systems of such transactions. What is most interesting about The Gift is how it de-mythologizes the idea that the giving of gifts is inherently selfless. Rather, a gift may be made to further a larger social or personal concern, while still enhancing the experience recipient of the gift.

What is a gift? The word itself is employed to cover a broad spectrum of intentions. One who “has a gift” may be observed to have a particular talent or skill that seems imbued by outside forces; the ability to play music, create art, dance, or otherwise use one’s body to mesmerize or create beauty. Such a deployment of the term tends to minimize the labor of the subject, as if “the gift” arrived fully formed. Philanthropists offer gifts to various communities, enabling the building of hospitals, museums, symphony halls, and community centers, and while some benefits flow to the individuals whose generosity makes such things possible, it does not necessarily diminish the value of the gift. Artists and creatives may use such gifts to create objects or events that move viewers through embodied experiences similar that feel very much like one is the recipient of something created solely for them. And, artists may use other gifts such as those that create the bond of community or mentoring skills to enhance our experience of the world.

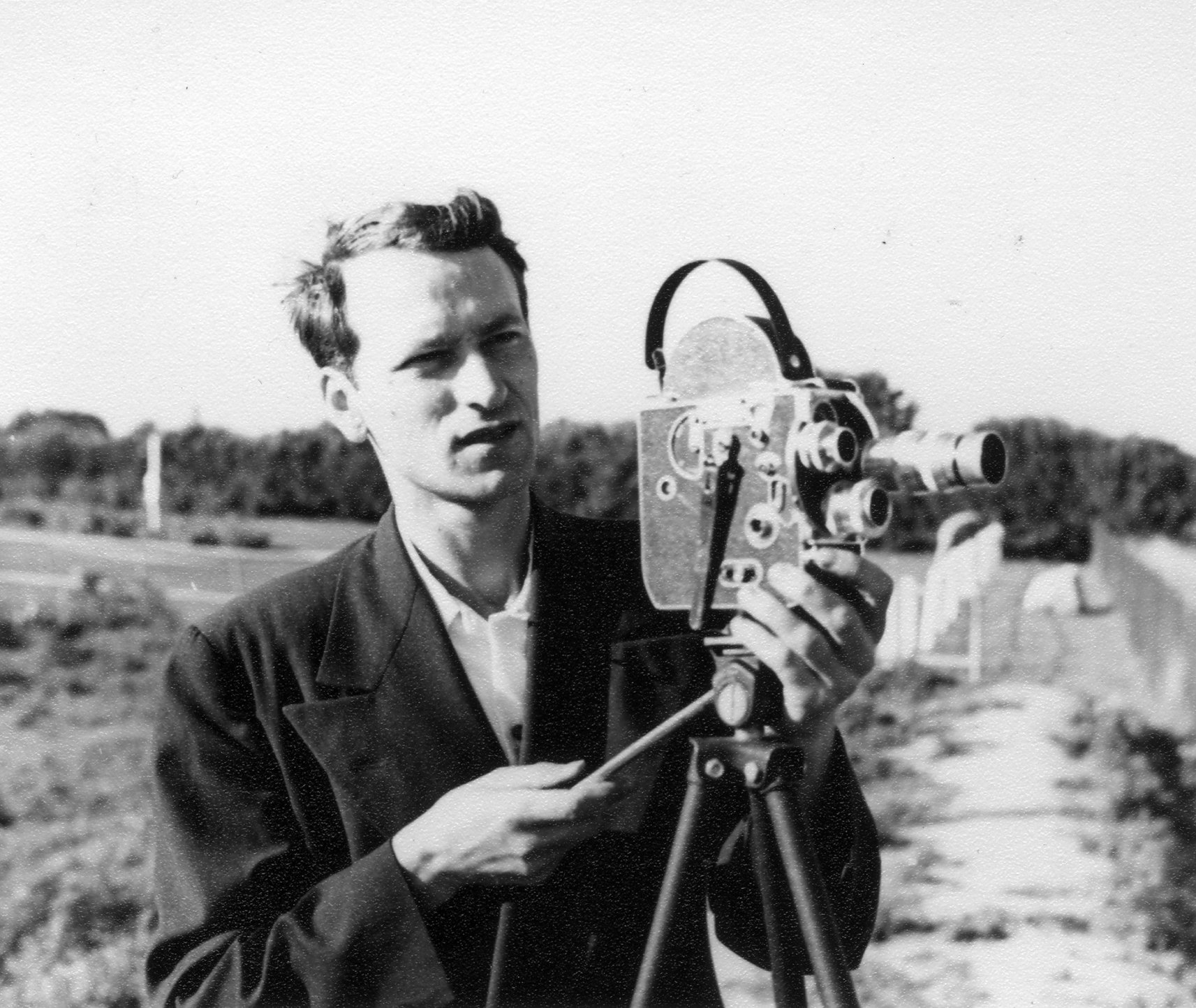

The filmmaker Jonas Mekas died recently at the age of 96, and, as is often the case, his gifts as an artist and as a kind of New York avant-garde impresario were known to a relatively small group of like-minded individuals who helped create an underground movement that embedded the art of film into the modernist cannon. Mekas’ use of the personal, autobiographical voice in film helped to articulate an important strand of practice in the nascent days of video art and also framed the postmodern era as a cinematic space, where the camera bears witness to the passing of time, the telling of stories, and the deconstruction of much of its own history previously told through the lens of mainstream Hollywood movie-making.

The filmmaker Jonas Mekas died recently at the age of 96, and, as is often the case, his gifts as an artist and as a kind of New York avant-garde impresario were known to a relatively small group of like-minded individuals who helped create an underground movement that embedded the art of film into the modernist cannon. Mekas’ use of the personal, autobiographical voice in film helped to articulate an important strand of practice in the nascent days of video art and also framed the postmodern era as a cinematic space, where the camera bears witness to the passing of time, the telling of stories, and the deconstruction of much of its own history previously told through the lens of mainstream Hollywood movie-making.

Mekas was born in Lithuania and with his brother, fled his home when the Soviets invaded in 1940, only to be imprisoned in a Nazi labor camp in Germany, then ending up in a displaced persons camp until around 1946. After studying philosophy in Germany for two years, he emigrated to New York and went on to work the luminaries of the avant-garde including the poet Allen Ginsberg, Andy Warhol, Yoko Ono, George Macunias (a founder of the Fluxus movement), and others. As he developed his personal vision of filmmaking within New American Cinema movement, he simultaneously began curating the work of fellow artists, writing about film, and developing venues for exhibition in New York. Between 1962 and 64, Mekas co-founded both the influential Filmmakers’ Cooperative and the Filmmakers’ Cinematheque, which ultimately became the landmark Anthology Film Archives, an institution that is still a vital part of film culture in New York and globally.

Mekas was an early adopter (or perhaps more accurately extended the vision of early 20th century polymathic, multidisciplinary impresario/artists) of a hybrid approach to participatory culture-making. As an inveterate start-up artist, he imbued creative spaces with personal histories, curatorial prerogative, often anti-establishment manifestoes and an indefatigable sense of purpose.

Jonas Mekas’ gift to many younger artists was a kind of road map that guided us through new possibilities of an art-life; one that was not limited to simply making and exhibiting, but described the kind of mash-up of creative outcomes that allowed for a deeply engaged vision of what art could be. He was, (before the term was hollowed out) an arts entrepreneur whose poetic vision of the world included bricks and mortar spaces where younger artists and filmmakers could sit in the dark and watch the work of visionaries who consistently pushed film and culture to their respective inflection points. Having the opportunity to screen one’s work at Anthology Film Archives was, for my generation (and me specifically), a gift that put us in the company of those to whose creative lives we would aspire.

Jonas Mekas’ gift to many younger artists was a kind of road map that guided us through new possibilities of an art-life; one that was not limited to simply making and exhibiting, but described the kind of mash-up of creative outcomes that allowed for a deeply engaged vision of what art could be. He was, (before the term was hollowed out) an arts entrepreneur whose poetic vision of the world included bricks and mortar spaces where younger artists and filmmakers could sit in the dark and watch the work of visionaries who consistently pushed film and culture to their respective inflection points. Having the opportunity to screen one’s work at Anthology Film Archives was, for my generation (and me specifically), a gift that put us in the company of those to whose creative lives we would aspire.

Douglas Rosenberg

Chair, UW-Madison Art Department