A recent article in New Yorker Magazine by Claudia Roth Pierpont recounts how a small group of women painters crashed the canvas ceiling as part of the historic Ninth Street Show, held amongst the cheap industrial spaces of downtown New York in 1951. The jury for the exhibition selected eleven women and sixty-one men to represent the nascent downtown art world, where a “creatively rich” but otherwise impoverished new art scene was taking hold.

A recent article in New Yorker Magazine by Claudia Roth Pierpont recounts how a small group of women painters crashed the canvas ceiling as part of the historic Ninth Street Show, held amongst the cheap industrial spaces of downtown New York in 1951. The jury for the exhibition selected eleven women and sixty-one men to represent the nascent downtown art world, where a “creatively rich” but otherwise impoverished new art scene was taking hold.  The article focuses mainly on Joan Mitchell, Helen Frankenthaler, Lee Krassner, and Grace Hartigan and talks about the Sisyphean task of finding visibility amongst the male painters who had dominated the Abstract Expressionist moment.

The article focuses mainly on Joan Mitchell, Helen Frankenthaler, Lee Krassner, and Grace Hartigan and talks about the Sisyphean task of finding visibility amongst the male painters who had dominated the Abstract Expressionist moment.

One of the unfinished undertakings of Western post-war art is not only carving out a feminist space for art, but beginning a project of undoing a deeply inscribed performance of masculinity that remains embedded in the mythologies of contemporary art, even while such histories are being continuously deconstructed. The idea of bending the materials of art to the artists will, of forcing ones desires onto the often-unyielding surfaces of canvas or iron or clay, is an exemplar of the way in which the very idea of masculinity is embedded in art practice. Man’s (historically) dominance over materiality generally forms the basis for much of our academic post-war art curriculum.

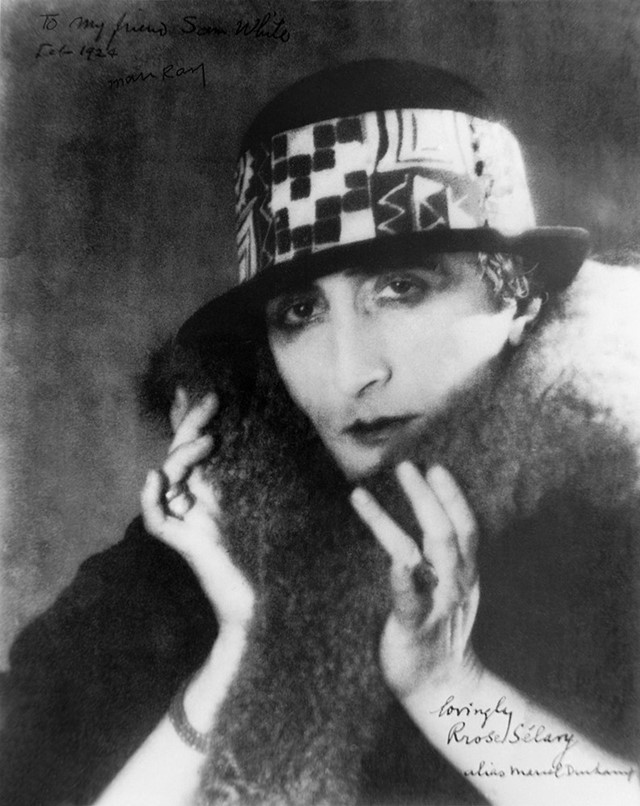

In the digressive turns of contemporary art history, even before the groundbreaking work of feminist artists in the 1970’s, there is a considerable, though less articulated, queering of such embedded masculinity.  For example, Marcel Duchamp, who is particularly well-known for his ready-mades, but perhaps less so for his experiments with gender (as Rrose Sélavy), occupies a space that seemingly rejects the historical notions of the masculine in Modern Art. Duchamp transferred his authorial imprimatur to his female alter ego, a gesture that is in a way, one of solidarity that unravels a number of existing tropes of the era. Rrose Sélavy (a pun on the French pronunciation Eros, c’est la vie “Sex, that’s life”) was photographed by Man Ray (around 1923), in his New York studio in the style of 1920’s glamour magazines, neither as a work of irony nor as a parody of femininity but rather as an extension of Duchamp’s ideas about doubling, both in meaning and in form (a urinal is not only a urinal but also a work of art), and Sélavy was Duchamp’s double or alter ego for decades; in 1965 Duchamp finally organized a dinner in her honor in Paris.

For example, Marcel Duchamp, who is particularly well-known for his ready-mades, but perhaps less so for his experiments with gender (as Rrose Sélavy), occupies a space that seemingly rejects the historical notions of the masculine in Modern Art. Duchamp transferred his authorial imprimatur to his female alter ego, a gesture that is in a way, one of solidarity that unravels a number of existing tropes of the era. Rrose Sélavy (a pun on the French pronunciation Eros, c’est la vie “Sex, that’s life”) was photographed by Man Ray (around 1923), in his New York studio in the style of 1920’s glamour magazines, neither as a work of irony nor as a parody of femininity but rather as an extension of Duchamp’s ideas about doubling, both in meaning and in form (a urinal is not only a urinal but also a work of art), and Sélavy was Duchamp’s double or alter ego for decades; in 1965 Duchamp finally organized a dinner in her honor in Paris.

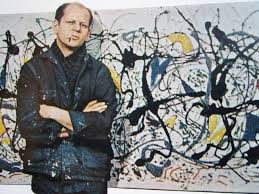

At the height of the McCarthy hearings, Abstract Expressionism was the reigning champ of modern art. On the surface it seemed apolitical, and it was practiced largely by men (or we were led to believe so). It was decidedly American both by critical decree and by the artists themselves. Ab-ex artists cultivated a particular brand of masculinity, one that circulated throughout the culture via magazine spreads and other forms of media.

The image of the artist bequeathed to the post-war avant-gardes was a fundamentally heroic one…

-Art Since 1900, Thames and Hudson

Masculinity was embedded in the very language used to describe work by Jackson Pollock and others.  The critic Clement Greenberg singled out Pollock as more “American and rougher and more brutal” than the European painters. Greenberg starts to hint at gender as a metric in his art criticism, implying that American art is, in general, more masculine than it European counterpart, which he and others implied to be “effete” and thus feminine. And who better to create such constructions of masculinity than Hollywood? Here, I am thinking about such images as those of James Dean from when he was starring in Rebel Without a Cause, a film that defined masculinity and rebellion as well as the kind of post war void of loneliness and émigré outsiderness.

The critic Clement Greenberg singled out Pollock as more “American and rougher and more brutal” than the European painters. Greenberg starts to hint at gender as a metric in his art criticism, implying that American art is, in general, more masculine than it European counterpart, which he and others implied to be “effete” and thus feminine. And who better to create such constructions of masculinity than Hollywood? Here, I am thinking about such images as those of James Dean from when he was starring in Rebel Without a Cause, a film that defined masculinity and rebellion as well as the kind of post war void of loneliness and émigré outsiderness.

However, again, masculinity is a complicated construction. And as all constructions tend to be, there are tensions that tug at any sort of purity or truthfulness, much in the same way that Greenberg’s ideas about purity as it relates to painting are, in the end, a construction. Such constructions are really more accurately a version of our own desires. However, humanism, sexual identity, equal rights, feminism, and the appropriation of historical art references all contribute to a new landscape at the mid-century, and hopefully continue to inform the way in which we create new, more open spaces for artists to exist within; such spaces that help move us beyond the rigid delineations of modernism and the imprint of masculinity on the art world in general.

Douglas Rosenberg

Chair, UW-Madison Art Department