The Findhorn Foundation, in northeast Scotland on the Moray Firth coast, is home to one of the oldest intentional communities in the world.

The Findhorn Foundation, in northeast Scotland on the Moray Firth coast, is home to one of the oldest intentional communities in the world.  Located between Inverness and Aberdeen, Findhorn evolved from a small experiment in communal and spiritual living in 1962 to be leading example of sustainable living through their ecovillage project, which is defined as being “ecologically, economically, culturally and spiritually sustainable.” The ecovillage grew out of the humble beginnings of a small garden in the untenable sandy soil of the windswept Findhorn Bay and the community’s work with spirit and nature. The Findhorn community is a place of wonder and generosity; some 400 people live in the village, trading labor for living, working in jobs that sustain the community while practicing their own life-journey. I have visited Findhorn twice as a part of an international group of artists and scholars who chose the site as a retreat venue. As we toured the village on my first visit, someone in our group asked if artists could trade their practice for room and board in this magical environment the way that those working in the kitchen or on building projects could. The surprising answer was no. It was explained that this question was debated with some vigor for a long time; if the arts were a part of a healthy and spiritually rich life then shouldn’t they be traded as other labor might be? In the end, the discussion was settled based on necessity; was art physically necessary for survival comparable to providing food, shelter, and other such basics of life? While all agreed that art made life better, they also acknowledged that a life could be made without art or at least one could trade other skills for shelter and food and practice art simultaneously.

Located between Inverness and Aberdeen, Findhorn evolved from a small experiment in communal and spiritual living in 1962 to be leading example of sustainable living through their ecovillage project, which is defined as being “ecologically, economically, culturally and spiritually sustainable.” The ecovillage grew out of the humble beginnings of a small garden in the untenable sandy soil of the windswept Findhorn Bay and the community’s work with spirit and nature. The Findhorn community is a place of wonder and generosity; some 400 people live in the village, trading labor for living, working in jobs that sustain the community while practicing their own life-journey. I have visited Findhorn twice as a part of an international group of artists and scholars who chose the site as a retreat venue. As we toured the village on my first visit, someone in our group asked if artists could trade their practice for room and board in this magical environment the way that those working in the kitchen or on building projects could. The surprising answer was no. It was explained that this question was debated with some vigor for a long time; if the arts were a part of a healthy and spiritually rich life then shouldn’t they be traded as other labor might be? In the end, the discussion was settled based on necessity; was art physically necessary for survival comparable to providing food, shelter, and other such basics of life? While all agreed that art made life better, they also acknowledged that a life could be made without art or at least one could trade other skills for shelter and food and practice art simultaneously.

I tell this story not to raise issues about art and its commodification or about labor itself. I am thinking more about how artists evolve their practice throughout the arc of a long, ever-evolving lifetime, and how the practice of art, like the practice of life, may find sustainability in such an evolution.

I began to think about this in earnest recently while having a discussion with my son about the difference between deciduous and evergreen trees. This discussion occurred as we were looking at two tree standing side by side, one with a few golden fall leaves still hanging on otherwise bare limbs, and the other a stately pine tree still a vibrant green seemingly unchanged by the season. In the field of botany the term deciduous means “falling off at maturity” usually in the autumn, or the shedding of petals or fruit after flowering. Staying with botanical meaning, the term evergreen is less metaphorical, though can denote something that is continuously renewed or is self-renewing. While both kinds of trees can be renewable or sustainable, their life cycles suggest radically different ways of being in the world, albeit an ecological or natural world.

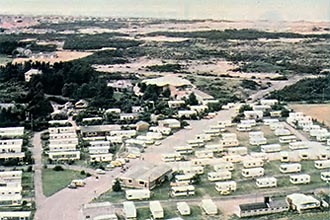

The Village of Findhorn looks nothing like it did at the time of its founding, originally a caravan park. As it has evolved toward sustainability, the architectural and physical changes of each successive era are still in evidence, like a kind of stratification or index of each change made visible. Style follows vision and dictates form in the visual culture of a community working toward a sense of itself and a sustainable future.

The Village of Findhorn looks nothing like it did at the time of its founding, originally a caravan park. As it has evolved toward sustainability, the architectural and physical changes of each successive era are still in evidence, like a kind of stratification or index of each change made visible. Style follows vision and dictates form in the visual culture of a community working toward a sense of itself and a sustainable future.

I wondered if the lives of artists might be thought of as either deciduous or evergreen as well, as cyclical and subject to the seasonal or temporal circumstances of age or illness or simply life itself? If sustainability is in part a product of allowing nature to inform the rhythm of life, our work habits, seasonal consumption of resources, and other such focused interactions with the places we inhabit, then a sustainable artists life would also include similar ebbs and flows, periods of growth and fallow periods as well. A deciduous artist may retreat from creative practice during such fallow times, instead seeking renewal and rebirth as the natural world does with the coming of spring. Having watched the growth of trees and crops around me over many seasons, it is clear that both have significantly more energetic growth at the start of their life, and more mature growth toward the end. Perhaps that makes sense in the context of a sustained and nurtured art-life; that artists, like nature need renewal time to evolve both their practice and how they integrate that practice over the span of a lifetime.

Douglas Rosenberg

Chair, UW-Madison Art Department