I often revisit texts which have had an impact on me in the past. Reading them in the present re-positions those essays, chapters, and books in my personal knowledge map. Some move toward the front, some recede into the background. It is a kind of knowledge tourism really, all done without leaving my own space. I have been thinking a lot about this “archive” recently, revisiting writings that explore the topic, as I ponder what exactly constitutes an archive and how it is different than an index, a collection, or simply memory.

I often revisit texts which have had an impact on me in the past. Reading them in the present re-positions those essays, chapters, and books in my personal knowledge map. Some move toward the front, some recede into the background. It is a kind of knowledge tourism really, all done without leaving my own space. I have been thinking a lot about this “archive” recently, revisiting writings that explore the topic, as I ponder what exactly constitutes an archive and how it is different than an index, a collection, or simply memory.

A career as an artist or scholar requires one to be continually moving forward, past one’s own history and into a sort of eternal present; constantly in the moment of creation of some sort or another. Such a constant workflow produces an almost unconscious archive of one’s activities and scholarly or artistic production.

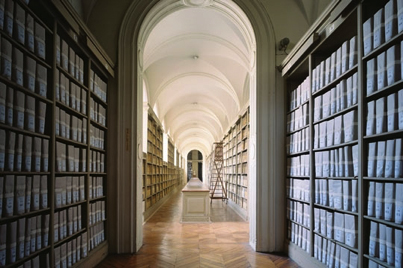

Listening to the way that scholars describe their research process recently, I was struck with their reliance on “the archive” or various archives, as a space of research; a place in which they situate themselves in order to sift through the collected thoughts and actions of others. While an outcome of such scholarly sifting and winnowing might be, for visual artists, a curated retrospective, for scholars it might take form as an essay or a book.  Perusing my own collection of books, (not an archive, more a random grouping of objects) I find Jacques Derrida’s Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression, which frames the archive historically as a place, generally in a private home, where “official documents are filed;” it is in this domicile “that archives take place” he says. Such archives, according to Derrida, were watched over by the state, magistrates with “authority” to do so. In the evolution of the archive, the opposite is now true; the public peruses the archive that is held by the state or by the local institutions as a kind of open space.

Perusing my own collection of books, (not an archive, more a random grouping of objects) I find Jacques Derrida’s Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression, which frames the archive historically as a place, generally in a private home, where “official documents are filed;” it is in this domicile “that archives take place” he says. Such archives, according to Derrida, were watched over by the state, magistrates with “authority” to do so. In the evolution of the archive, the opposite is now true; the public peruses the archive that is held by the state or by the local institutions as a kind of open space.

However space alone is not an archive, and objects merely situated in that space does not further constitute an archive. In The Lure of the Local, Lucy Lippard parses the meaning of space itself noting that, “Space defines landscape… space combined with memory defines place.”

So, it is at the intersection of space, place, and memory that the archive comes alive. Archives require a guide to fully function, to be more than a collection of objects suspended in time. Thus, in the exhibitions of contemporary art, we find wall texts and notes, essays and catalogs which function as ersatz docents (we find them in the spaces of art as well), guiding us toward a kind of hidden logic or a thesis that connects the objects or gestures in our field of vision to each other and to history.

Derrida asks us to consider the mechanisms of how we archive and, further, how we decide what to archive. And this is the dilemma of both artists and scholars in the digital age as well. While tacitly aware that everything which is created and documented has a digital afterlife, what do we actively steward and when do we look back at such archives? And what do we do with the physical detritus and material objects produced by individuals in the search of answers to questions that are thought through in material and by hand-work? I am aware that these are rhetorical questions, however, I pose them so that I can think them through for myself, and so I can reach into my own archive (or collection) of objects in order to excavate potential answers.

Douglas Rosenberg

Chair, UW-Madison Art Department