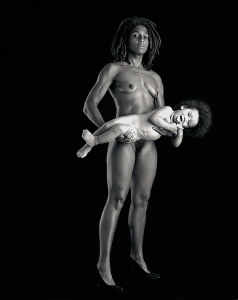

I gave a lecture to my Contemporary Art History class recently called Slippages and Resets: Re-booting Identity and Jump-starting the Art World. It begins with a performative, photographic self-portrait by the artist Renee Cox, Yo Mama, from 1993.

I gave a lecture to my Contemporary Art History class recently called Slippages and Resets: Re-booting Identity and Jump-starting the Art World. It begins with a performative, photographic self-portrait by the artist Renee Cox, Yo Mama, from 1993.

Yo Mama by Renee Cox, 1993

It is a self portrait that, in one glance, illuminates the real world experience of the artist; an identity that is at once complicated and rare if considered in the larger historical context of contemporary art. Cox’s Yo Mama makes a clear statement about her identities (plural) as mother, Caribbean, African, and American; woman, sexual-being, feminist. It is a part of a larger series of work in which she places herself in real life situations, pregnant, with her children, her family, with friends and in the context of a member of an ethnically and racially defined social and economic condition.

As I reflect on what I am sharing with my students in these lectures, I have become conscious that we seeing a lot of what seems to be a particular kind of work this semester. Work that is often body-based, concerned with cultural taboos and often offensive in some way to at least one constituency and maybe more. It is also work that is increasingly global, spread across gender and often revisionist. I am also conscious that I am re-writing my lectures more than usual to accommodate for new voices that are making their way to the leading edge of the discourse of contemporary art. Voices, which in many cases, such as that of Renee Cox, have been hiding in plain sight.

Portrait of Baya & Femme robe jaune cheveux bleus (Woman with blue hair in a yellow dress) by Baya, 1947

Other voices from the earlier period of modernist art historical narratives are being drawn into focus as well. In that same lecture, I added new images and information about an artist called Baya, whose work has been “discovered” of late, even though she was a contemporary of Picasso and Matisse.

Recently featured in an exhibition at New York University’s Grey Art Gallery, her story brings to mind Linda Nochlin’s rhetorical question about why there have been no great women artists. Baya (born Fatima Haddad in Algiers, at the North-Western tip of Africa in 1931) was orphaned at age five and raised on the family farm by her grandmother. Her early interest in art was nurtured by the woman who adopted her in her teen years, her adoptive French intellectual Marguerite Camina Benhoura, and eventually led to an exhibition at age sixteen in Paris. The exhibition, organized by the art dealer Aime Maeght, featured Baya’s watercolors and caught the attention of such luminaries as the Surrealist André Breton and Pablo Picasso. Her paintings are described as colorful, spontaneous and “childlike” compositions and the curator of the show at NYU, Natasha Boas notes, “Her work allows us to question so many different histories… The outsider. The outlier. The woman artist.”

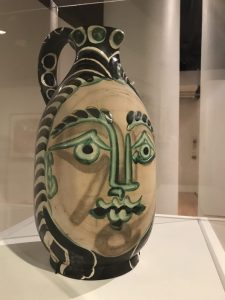

Bearded Man’s Wife by Pablo Picasso,1953

Recent writing about Baya describes a familiar scenario; at Galerie Maeght, Picasso discovered the young artist’s work on paper and canvas as well as her painted and brightly colored ceramics and soon began producing ceramic sculptures “influenced by” Baya’s own work. Attributing this new direction to Baya’s inspiration, he worked with her on a series of projects at the Madoura pottery workshop in Vallauris, a small town in the southeast of France.

Baya’s work is deeply rooted in the natural world she experienced as a result of her North African heritage and her paintings weave together a symbolic array of female figures, fish, birds, along with patterns that recall Islamic art and Arabic calligraphy. Critics note that Baya created her own artistic language, fusing North African Maghreb folklore and French Modernism. Absent from the art world during the time of the Algerian War (between 1955 and into the late 60’s) she subsequently resurfaced in exhibitions around France and elsewhere.

Clearly historical texts about art in the 20th and 21st centuries are in need of almost constant re-writing and revision, of remediation and correction. Given the speed at which new versions of old histories are pushed toward us in the digital age, printed texts may become inaccurate almost as they are written.

I was surprised and happy to see a feature in the most recent issue of Artforum on the experimental filmmaker Barbara Hammer. Hammer’s films, pioneering “queer cinema” in the 70’s were a staple in arthouse screenings and in my own art school education. Hammer’s radical use of screen space and frank engagement with personal narrative and sexuality bridged the transition from experimental film to video art and was an aspirational model for early West Coast forays into the territory of highly personal video-making. Hammer’s films, addressing as they do, issues particularly specific to women and to feminism, has been denigrated as essentialist during her long career. Hammer notes that the “pejorative” deployment of that term was “a real attempt to silence a lot of us.” Perhaps the art world is experiencing its own moment of awakening and realizing the utopian and egalitarian possibility of re-enfranchisement; a moment when, given the speed in which new historical knowledge finds an eager audience, history books are indeed outdated as even they are written.

Very best,

Douglas Rosenberg

Chair, UW-Madison Art Department