I want my students to know everything that I know; all of the history of contemporary art, all of the annotations of that history, all the artists that inspired and continue to inspire me, the films, exhibitions, and cultural events I have witnessed. I want them to know these things so that I can share the joy that they have brought to me, the challenges, and the knowledge that these experiences have illuminated. I also know that this is almost impossible. Every experience takes up its own space in ones memory bank and as new things enthrall us, something has to give way to open space for the embodiment of more contemporary experiences.

I want my students to know everything that I know; all of the history of contemporary art, all of the annotations of that history, all the artists that inspired and continue to inspire me, the films, exhibitions, and cultural events I have witnessed. I want them to know these things so that I can share the joy that they have brought to me, the challenges, and the knowledge that these experiences have illuminated. I also know that this is almost impossible. Every experience takes up its own space in ones memory bank and as new things enthrall us, something has to give way to open space for the embodiment of more contemporary experiences.

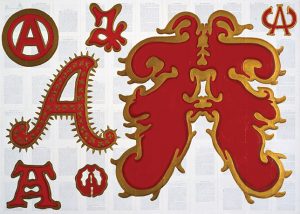

Tim Rollins and K.O.S.

This came to mind as I recently discovered that the artist, educator, and activist Tim Rollins had died. I was trying to describe his work to someone recently and thought to refresh my memory of some of that work. In doing some research, I realized that he had been ill and in fact had passed away, unbeknownst to me, in December of last year. He was best known for his work as Tim Rollins + KOS (Kids of Survival), a decades-long collaboration with a group of students from the South Bronx.

Tim Rollins and K.O.S. The Scarlet Letter – The Prison Door (after Nathaniel Hawthorne), 1992-93

While working as a substitute teacher in New York City, Rollins was invited to develop a special-education program for students with learning disabilities that combined making art with improving reading and writing skills. The project, which began at I.S. 52, a junior high school in the South Bronx in the 1980’s, became legendary and their work was featured in important venues including two Whitney Biennials, the Venice Biennale, Documenta 8 in Kassel, Germany, and at the Dia Art Foundation in Chelsea. I was saddened to learn of Rollin’s passing and equally saddened to think about how many younger artists may now never hear of this important and inspiring body of work. And while the new technologies of the internet, the cloud, and other data organization protocols promise to make space for virtually everything that has or will exist, humans are not built with enough memory space to recall the same.

Everything Is Illuminated, Liev Schreiber, 2005

Toward the end of Everything is Illuminated, the film based on the book of the same name by the author Jonathan Safran Foer, the story’s main characters stand at the end of a long walkway flanked by vast fields of sunflowers. At the other end of the walkway is a somewhat decrepit house, crisp white sheets on clotheslines snapping in the breeze, an image that stands out in sharp contrast to the deep yellow of the sunflower fields that surround it. We come to find out that in the house is a very old woman who is the keeper of memories for a village whose population has all but disappeared. In one room are boxes perfectly stacked from floor to ceiling, which contain the keepsakes and treasures of all the stories of all the people who had come and gone from the village of Trachimbrod; the objects are mnemonic devices for remembering. The boxes look eerily similar to the stacked bisquit tins that the artist Christian Boltanski uses to recall the disappeared children of his village during World War II. The house that the characters Jonathan, Alex, and Grandfather arrived at is the archive of the village, the place where its histories are entrusted and all its stories can be retrieved through the memory of its inhabitant.

In Archive Fever, A Freudian Impression, the philosopher Jacques Derrida traces the term “archive” to its Greek origins where it meant, “a house, a domicile, an address, the residence of the superior magistrates, the archons, those who commanded.” The residents of these domiciles, due to their political power, were entrusted with official documents to be kept in the place that was their home:

Entrusted to such archons, these documents in effect speak the law . . . they needed at once a guardian and a localization… The dwelling, the place where they dwell permanently, marks this institutional passage from private to public.

Permanence, in a digital culture, is a moving target; the bricks and mortar dwellings, the archives that Derrida describes, are increasingly giving way to online or digital venues, and thus, as more and more archives become digital, the passage from private to public becomes less local, less site-specific. In a sense, as artists and teachers, this is the dichotomy with which we wrestle in the twenty-first century. What do we archive, how do we archive? And further, how does anyone know what is in the archive?

I find, more and more, in classroom situations and in conversation with students and others, that I am reciting the names of earlier generations of artists as often as possible, telling their stories in order to inscribe their memories and in order to inspire a sense of inquisitiveness about their work amongst those unfamiliar with the likes of Tim Rollins + KOS.

Very best,

Douglas Rosenberg

Chair, UW-Madison Art Department