No longer do we accept the ‘sublimation model’ according to which ‘the function of art is to sublimate or transform experience, raising it from ordinary to extraordinary, from commonplace to unique, from low to high.

Rosalind E. Krauss, October 56, Spring, 1991

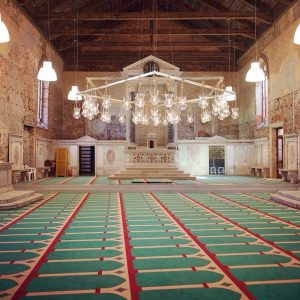

Christoph Büchel, a Swiss artist, is known for “transforming art spaces and other public institutions with hyper-realistic, walk-in installations that skewer the hypocrisies and political contradictions of the art world and the world in general.” For his project at the Venice Biennale this summer he transformed an unused 10th Century Catholic church, into a functioning mosque which serves as Iceland’s national pavilion. In spite of its links to the Muslim world, the City of Venice has never permitted the establishment of a mosque in its historic center.

The Mosque, Christoph Büchel

For The Mosque, Büchel covered much of the historically significant religious imagery and artifacts with Arabic script and Islamic motifs in order to transform the space into a sacred space of worship; one that spoke to the traditions and visual culture of Islam. Shortly after its opening, and after hundreds had come to the space to worship or to simply experience it as a work of art, it was shut down by Venetian authorities who cited safety and other concerns.

Certainly this was a provocative work of art, whose outcome might have been foreseen (creating a mosque inside a Catholic church), however, as a catalyst for dialog, it forces us to consider a number of questions. As a public work of art, to whom is it addressed? We can surmise that within the global construct of the Biennale this work was addressed to the Art World writ large; to the humanistic concerns of an international community focused on social justice, democracy, the politics of identity, and on politics in general, all within the frame of both esthetics and the pale of history. Arthur Danto notes that after “the end of art,” everything is permitted. However, Büchel ignited a fuse that quickly lead to its own demise.

Therein lies the dilemma of theory and possibly, the dilemma of Art.

I like order. Order allows for the making of meaning within a set body of rules. For instance, manifestos provided order; Dada was Dada, Futurism was Futurism, etc. Art without manifestos is disorderly, unkempt and inscrutable. And this is where theory proves useful.

Theory grounds a dialog and provides landmarks and anchor points in the same way that manifestos created an orthodoxy of art, for the moment, and for the group that adhered to that particular set of rules.

Unlike history, theory does not fix or judge or create exclusionary narratives. Theory suggests paradigms for framing and for understanding. It offers a set of possibilities for understanding the gesture of art, for aligning works of art within a community of ideas; it is experimental thinking that suggests a set of possibilities for what we might consider when we consider art.

Physics has laws; we come to know them when we gesture toward or otherwise push up against them. Philosophy has regulated methods of inquiry such as semiotics, structuralism, and poststructuralism; we use those tools to illuminate new meanings in the visual arts. We also rely on such frameworks to critique the way others write and publicly think about art.

Art is not monolithic, and not all art subjects itself to theoretical scrutiny. However, all art is within the purview of theorists and those who might use it to demonstrate a larger narrative in general about the human condition.

Rosalind Krauss is a groundbreaking scholar and founder of the influential journal October, a writer for Artforum, and a theorist who has used the tools of psychoanalysis, structuralism and art history itself to define entire fields of practice. Krauss observed that art may serve more than the “discourse of originality,” and that it might indeed accomodate “much wider interests… fueled by more diverse institutions—than the restricted circle of professional art-making.” Büchel’s immersive work-of-life, as described above, illustrates Krauss’s theories (and likewise Danto’s) written years prior. That is what theory often does; it lies dormant waiting to be illuminated by artists either with or without knowledge of such prognostications.

Very best,

Douglas Rosenberg

Chair, UW-Madison Art Department