I’ve been thinking about the idea of the sequence lately. When I think about sequential mark-making, Braille and Morse code come to mind as does the I-Ching, related as they are by the repetition of simple dots or dashes in groups that acquire meaning through sequencing. I am thinking too about the way in which music is notated on the page, the cascading arcs and curves of notes on the staff telegraph sound through visuality to even those untrained in the form. I am thinking of the serial music of Steven Reich in the late 1960’s-70’s, pieces such as Clapping Music or Drumming; compositions that framed music as part of the larger minimalist movement in general (along with Terry Riley and Phillip Glass).

I’ve been thinking about the idea of the sequence lately. When I think about sequential mark-making, Braille and Morse code come to mind as does the I-Ching, related as they are by the repetition of simple dots or dashes in groups that acquire meaning through sequencing. I am thinking too about the way in which music is notated on the page, the cascading arcs and curves of notes on the staff telegraph sound through visuality to even those untrained in the form. I am thinking of the serial music of Steven Reich in the late 1960’s-70’s, pieces such as Clapping Music or Drumming; compositions that framed music as part of the larger minimalist movement in general (along with Terry Riley and Phillip Glass).

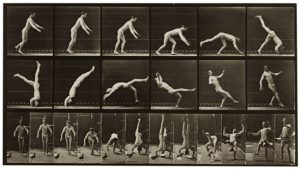

Detail from Eadweard Muybridge’s ‘Head-spring, a Flying Pigeon Interfering’

I also think about how photography in the hands of Eadweard Muybridge or Étienne-Jules Marey made us think about the “present” in a wholly different way in the late 19th century as they developed proto-cinematic techniques of sequential photography that extended and dramatized the “moment” or the present. Such images, as they were, bookended by the moment just before and the moment just after, seem scientific now, seemingly portraying a kind of evidentiary phenomena related to sequential time as bounded by the images to the left and to the right.

Vito Acconci – Following Piece

In the earliest days of my own art life I was quite mimetic; I think I attempted to understand the world through copying. That is to say that often, I would see an image in a book or a painting on a wall or a dance performance on television or in the theater and, if it caught my fancy, I would mimic it. I would go back to my studio or my house and try to make a painting like Julian Schnabel or a performance that echoed Samuel Beckett or a dance that looked as much as possible like my understanding of modern dances that I saw South of Market St. in San Francisco. Much of my understanding of the art world in my twenties was from books, the kind of exquisite exhibition catalogs or monographs that we don’t see much anymore in which there were pages of photos, often in black and white, that documented performances, installations, dances, and other ephemeral or time-based work. Such documentation was often sequential, with numerous pictures of an event or project situated in chronological order, visually explaining the unfolding of a temporal and often corporeal and gestural work that lived in the interstices between codified genres of arts practice. Works by Vito Acconci (Following Piece) and Yoko Ono (Cut Piece) or Carolee Schneemann’s Interior Scroll and later work by Suzanne Lacy and Sharon Allen (Whisper the Waves, the Wind) come to mind as being related through their reliance on both temporality and narrative unfolding as well as by sequential photo documentation; the kind of bookending of the moment by stills taken just before and after the present. It was in these interstitial spaces, the moments in between and the spaces of overlap that photo based documentation was so valuable. In such complex work, a picture was often worth far less than 1000 words. A single picture reduced a complex temporal work to a cypher or a signifier, which in the contemporary parlance of branding may have been a positive in some situations, though it was reductive and ran the risk of confusing the viewer; was this a snapshot or a tourist photo or was it an amateur record of some odd event; it was just not clear. However, sequential documentary photography seemed to lend a sense of gravitas to such work. It began to echo other methods of knowing and to resonate through repetition. It alluded to film and cinema, to the triptych of religious painting and to the formal repetitive nature of ritual by which something transforms by restating, its aggregate meaning a gestalt of all that is contained in the layers and overlaps where content is gestated through accretion. Photography informs contemporary art through osmosis; its presence is ubiquitous and contemporary screen technologies prosthetically extend its reach. Although I wonder how different that is than my books and their sequentially numbered pages, indexical arrangements of mysterious images such as those I attempted to imitate like a scribe might replicate a sacred text.

Douglas Rosenberg