There is a 16th century Kabbalistic story that describes how all of the light in the world was originally contained in ten vessels. However, it seems that the vessels were too fragile to contain so much energy, and they quickly broke apart, sending sparks and light everywhere out in the world. In this story, until all of the light has been returned and the vessels repaired, the world will be in constant need of repair.

There is a 16th century Kabbalistic story that describes how all of the light in the world was originally contained in ten vessels. However, it seems that the vessels were too fragile to contain so much energy, and they quickly broke apart, sending sparks and light everywhere out in the world. In this story, until all of the light has been returned and the vessels repaired, the world will be in constant need of repair.

I am thinking here about the artist Arlene Shechet, whose large-scale works in clay seem to contain the possibilities of such repair and restoration; a sort of invitation to healing and to the sense that there is a larger purpose to art, beyond esthetics or beauty. In a recent interview about her work and process, Shechet was asked, “What part does the vulnerability of the material play in things?” She answered:

I am thinking here about the artist Arlene Shechet, whose large-scale works in clay seem to contain the possibilities of such repair and restoration; a sort of invitation to healing and to the sense that there is a larger purpose to art, beyond esthetics or beauty. In a recent interview about her work and process, Shechet was asked, “What part does the vulnerability of the material play in things?” She answered:

I’m not sure what the vulnerability of the material means but I think the artist is the vulnerable actor and the material is just a blank slate. The “vulnerability of the material” perhaps refers to the fact that it can be broken…everything can be broken or damaged… as this reflects the human condition and what it’s like to live life within a body.

The Kabbalist might propose that until everyone and everything has been repaired, the work of the world is incomplete. What are we to make of such work in this moment when we are confronted with the sort of images this current pandemic offers up?

In speaking of Shechet’s work, Kara L. Rooney notes:

The figure is almost always referenced in the artist’s work, yet simultaneously expelled from the garden of reasonable interpretation.

Her description of Shechet’s work suggests corporeal forms as bodies in disrepair, broken or wracked with pain, their psychic energy depleted and longing for comfort, rehabilitation or restoration.

In a recent piece in The Guardian, the art writer Olivia Laing talks about art as a “vital precursor to change” that may help us to process the flood of images that wash over us each day; mediated reminders of the plight of our world before, during and after this moment.

Laing says, “Art can’t forcibly induce a change in behavior. It’s not a re-education pill. Empathy is not something that happens to us when we read War and Peace… art can, however, provide us with radiant materials.” And by materials, she means the work-product of artists, the things that artists make themselves while contemplating the often existential nature of the world. She goes on to state, “Art can’t win an election or bring down a president. It can’t stop the climate crisis, cure a virus or raise the dead. What it can do is serve as an antidote to times of chaos. It can be a route to clarity, and it can be a force of resistance and repair, providing new registers, new languages in which to think.”

Resistance and repair… perhaps a talisman for hope.

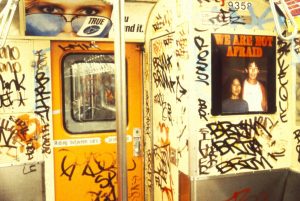

In 1981, the artist Les Levine created a project for the New York City Subway called We Are Not Afraid. At the time, the subways were not a safe place for many people and there was increased hostility toward immigrants in general. Levine’s simple image of two Asian people under the title of the work was installed on some 4800 subway cars across the city. Some New Yorkers also noticed the significance of its message of hope for the AIDS pandemic that was engulfing the city at the time, which members of the Gran Fury artist collective were also addressing through guerrilla dissemination tactics in New York and elsewhere.

In 1981, the artist Les Levine created a project for the New York City Subway called We Are Not Afraid. At the time, the subways were not a safe place for many people and there was increased hostility toward immigrants in general. Levine’s simple image of two Asian people under the title of the work was installed on some 4800 subway cars across the city. Some New Yorkers also noticed the significance of its message of hope for the AIDS pandemic that was engulfing the city at the time, which members of the Gran Fury artist collective were also addressing through guerrilla dissemination tactics in New York and elsewhere.

The vulnerability of materials, of people, of art, generally, inspires us to be caretakers for each. And as Laing notes, while “art can’t forcibly induce a change in behavior,” it can focus our attention and make us empathetic stewards of our communities and of the art they create. That is indeed a step toward repairing the world.

Douglas Rosenberg

Chair, UW-Madison Art Department