I’m feeling grateful for the health of our community and I am also feeling a lot of anger for things I cannot control. I feel, quite literally, stopped in my tracks, forward motion seems all but halted and, while working hard to adapt to this new reality, I am increasingly looking for prompts to keep me focused. I find myself scanning through a stack of books that all share common themes about enchantment, the spiritual in art, quotidian practices, and everyday generosity.

I’m feeling grateful for the health of our community and I am also feeling a lot of anger for things I cannot control. I feel, quite literally, stopped in my tracks, forward motion seems all but halted and, while working hard to adapt to this new reality, I am increasingly looking for prompts to keep me focused. I find myself scanning through a stack of books that all share common themes about enchantment, the spiritual in art, quotidian practices, and everyday generosity.

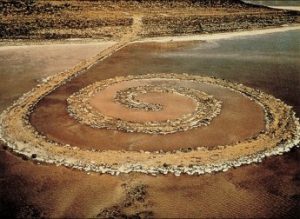

I am drawn, at this moment, to the work of artists that places the viewer in a space of contemplation, that forces me to contemplate both the beginning and the end of the gesture; work that is simultaneously finite and infinite.  As I think about being stuck in this cyclical moment where we are all held in place, unable to progress, I begin to see the work of artists such as Richard Long, Agnes Denis, and Robert Smithson (among others) as statements of repurposed anxiety; anger, rage, dis-enchantment with the era in which they were working, channeled into sublime and meditative projects aimed at creating a measure of solace for themselves and for others.

As I think about being stuck in this cyclical moment where we are all held in place, unable to progress, I begin to see the work of artists such as Richard Long, Agnes Denis, and Robert Smithson (among others) as statements of repurposed anxiety; anger, rage, dis-enchantment with the era in which they were working, channeled into sublime and meditative projects aimed at creating a measure of solace for themselves and for others.

If being stuck, or stuck in place, is a kind of entropy, then what if moving forward is circling back to the of beginning and retracing one’s steps? Isn’t that still a kind of progress that builds on one’s entire artistic practice to the point fixity, to this moment in which we have become unmoored is so many ways? If an artist who previously made work out in the world is now making work in their kitchen, can that still be of value even if it seems to be a kind of backward trajectory? I think so.

The anger I mentioned earlier can be a powerful force for both personal and cultural change.  Artists have historically channeled their anger forward through their practice as they fought for change and a more egalitarian world, as in the case of Agnes Denes, the artist who created one of the most important and ephemeral artworks in the history of New York City. In Wheatfield — A Confrontation, Denis planted a two-acre wheat field in May, 1982, on the landfill that become Battery Park City. Her crop was harvested that August and then disappeared forever from the site. Her gesture was part protest, part social justice, and ultimately created, if for a short time, as a place of repose in an otherwise inhospitable landscape.

Artists have historically channeled their anger forward through their practice as they fought for change and a more egalitarian world, as in the case of Agnes Denes, the artist who created one of the most important and ephemeral artworks in the history of New York City. In Wheatfield — A Confrontation, Denis planted a two-acre wheat field in May, 1982, on the landfill that become Battery Park City. Her crop was harvested that August and then disappeared forever from the site. Her gesture was part protest, part social justice, and ultimately created, if for a short time, as a place of repose in an otherwise inhospitable landscape.

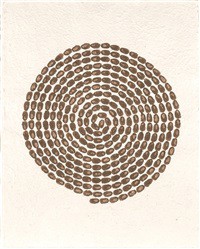

Artists speak to trauma in many ways, but I notice recurring themes of repetition, simplification, and ritual across numerous works and historical moments.  The artist Jivya Soma Mashe (1934-2018) lost his mother at the age of seven and subsequently stopped speaking for several years. He communicated by drawing pictures in the dust in his village of Maharashtra, India. Later, he began working in the traditional style of the Warli community, employing a 1200-year-old method of image-making that was a part of ritual life, later evolving into storytelling and narrative mythology.

The artist Jivya Soma Mashe (1934-2018) lost his mother at the age of seven and subsequently stopped speaking for several years. He communicated by drawing pictures in the dust in his village of Maharashtra, India. Later, he began working in the traditional style of the Warli community, employing a 1200-year-old method of image-making that was a part of ritual life, later evolving into storytelling and narrative mythology.  The circular, hypnotic forms of his paintings, perhaps begun in trauma, evoke later works by such artists as Richard Long or Robert Smithson.

The circular, hypnotic forms of his paintings, perhaps begun in trauma, evoke later works by such artists as Richard Long or Robert Smithson.

The artist and writer Suzi Gablik’s 1991 book The Re-Enchantment of Art addresses her growing discomfort with “the compulsive and oppressive consumeristic framework in which we do our work,” noting further that “we live in a culture that has little capacity or appreciation for meaningful ritual.” For Gablik, it is in ritual that we find peace or heal or give ourselves permission to play, to step out of the rigors of art as a career and remember what art can do for the soul. Most of the time, this is a choice, a product of free will, sometimes it is a necessary step back from the world, and sometimes it is forced upon us by uncontrollable circumstances. At this moment of forced regression, sending many of us back to the beginning, to the kitchen table, computer screen, or elsewhere to practice our creativity and to speak to the world in a much smaller voice, perhaps we are being given a prompt; to focus on our faith in art, transformation, and the elevation of the ordinary and to become re-enchanted with art in the meantime.

Douglas Rosenberg

Chair, UW-Madison Art Department