There is a balm in Gilead

to make the wounded whole.-Traditional Hymn

Why make art? Answers to such a question would vary of course, depending on who is asked; what their particular life experience is in relation to the practice of art, even the definition of art itself.

Perhaps one answer is to make the wounded body of art whole again; in other words to repair the cannon through the act of making the wound visible while simultaneously offering a balm or a curative.

-Rebecca Belmore, Fringe, 2007

I recently had a conversation with a colleague of my generation that was illuminated by our shared history of the era of post-structuralist theory. Suddenly, our conversation came into focus and moved forward quickly through a series of shorthand references to Judith Butler, Jean Baudrillard, Foucault and others; the fact, that we both had such a code in our art-practice DNA, it allowed for an assumption of foundational knowledge full of alliances, contextual information and, in a way, a kind of political affiliation. Theory, and allegiance to it, is a kind of theology, a belief system, that in the case of post-1960’s globalism is predicated on the idea that art can change the world and make it a better place for all people.

Post-structuralist thinking suggests that to understand an object (or a text), it is necessary to study both the object itself and the systems of knowledge that produced the object. So, in order to change the systems of art, for instance, the way in which art circulates and the possibilities of what art and artists can contribute to the world, the systems by which art is taught and traded must also change. This idea is at the core of Linda Nochlin’s seminal essay from 1971, Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? Nochlin argued that to understand the general question, one needed to interrogate the entire system that created the circumstances by which women were absent from the art world and the ensuing canon. She suggested that by investigating the context of the systems of art, one might arrive at a rigorous, authentic understanding of the facts of art history in general, including the question her essay proposed.

The challenge to the canon of art up to mid-20th century was indeed a by-product of both activist art-making and equally activist theory-making, and the result of that is evident in a strand of contemporary art that is grounded in empathy for both people and for the spaces they inhabit.  I am thinking about the work of Agnes Denis, whose project, Wheatfield – A Confrontation, 1982, supported by New York’s Public Art Fund, radically re-thought Land Art and alerted us to the possibility that art could help to reclaim fouled landscapes. Denis’ seemingly simple gesture in which she planted a field of golden wheat on two acres of a garbage and rubble-strewn landfill near Wall Street illuminated a politics of consumption at the cost of a scarred and wasted landscape.

I am thinking about the work of Agnes Denis, whose project, Wheatfield – A Confrontation, 1982, supported by New York’s Public Art Fund, radically re-thought Land Art and alerted us to the possibility that art could help to reclaim fouled landscapes. Denis’ seemingly simple gesture in which she planted a field of golden wheat on two acres of a garbage and rubble-strewn landfill near Wall Street illuminated a politics of consumption at the cost of a scarred and wasted landscape.

I am also thinking about the artist Mona Hatoum, whose work reverses the history of an art that imports culture to the West, mediated by a gaze that is not authentic but rather exerts ownership over all it surveys.

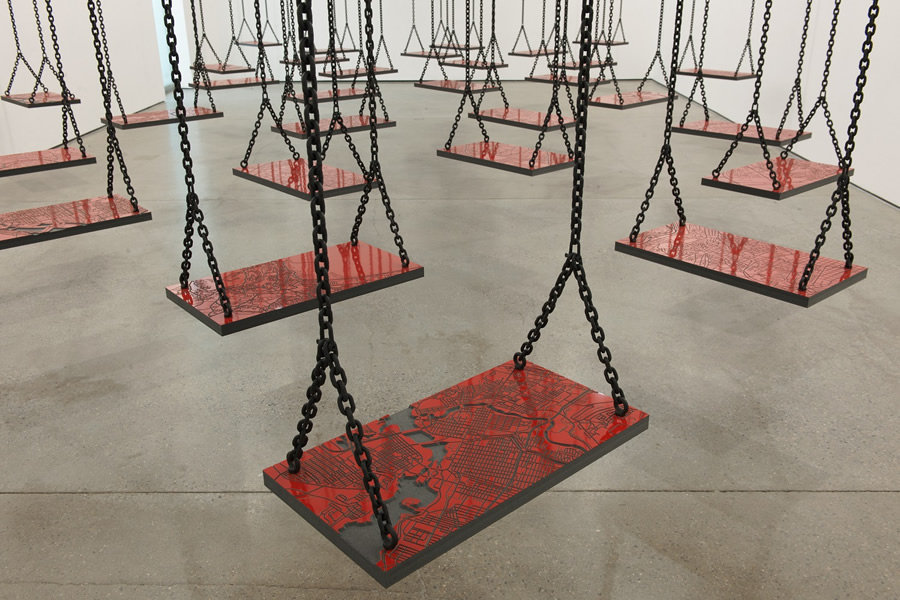

Hatoum’s evocative installation Suspended, includes 35 wooden swings, each embossed with the street map of a capital city randomly chosen from each of the six continents of the world. The work suggests the perpetual dislocation and uncertainty of immigrants and refugees, a condition that framed Hatoum’s own life. Now, through the work of Hatoum and other diasporic émigré artists, such culture-work is being delivered directly to the viewer without intermediary or translation. It is set gently in front of us as both a contemplative questioning of our own ethos and as an introduction to things we use to only know in translation, as a colonized experience.

Hatoum’s evocative installation Suspended, includes 35 wooden swings, each embossed with the street map of a capital city randomly chosen from each of the six continents of the world. The work suggests the perpetual dislocation and uncertainty of immigrants and refugees, a condition that framed Hatoum’s own life. Now, through the work of Hatoum and other diasporic émigré artists, such culture-work is being delivered directly to the viewer without intermediary or translation. It is set gently in front of us as both a contemplative questioning of our own ethos and as an introduction to things we use to only know in translation, as a colonized experience.

Douglas Rosenberg

Chair, UW-Madison Art Department