The very principle of photography is that the resulting image is not unique, but on the contrary infinitely reproducible. Thus, in twentieth‐century terms, photographs are records of things seen.

-John Berger, Understanding a Photograph

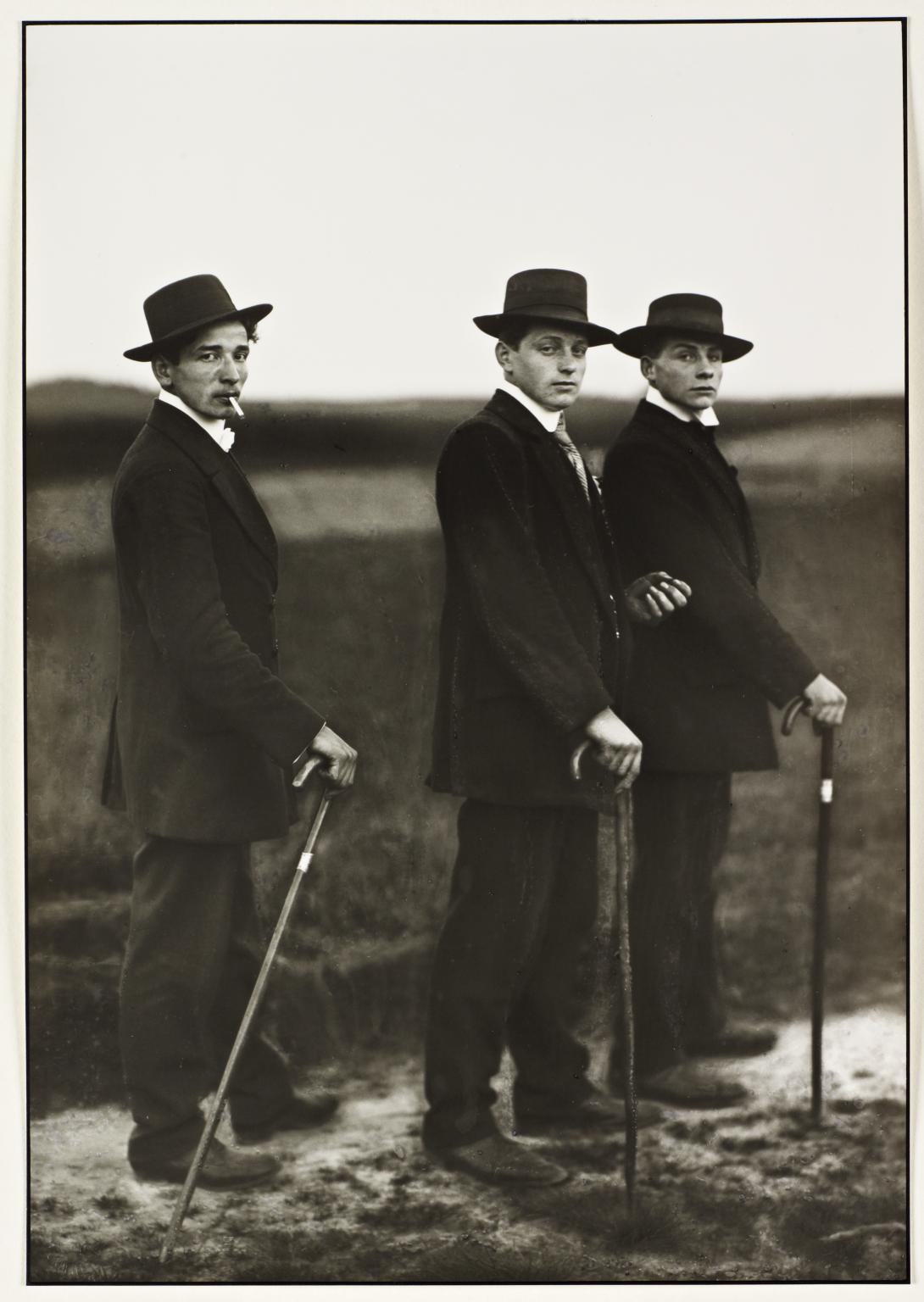

In John Berger’s book, About Looking, the author spends a significant amount of time contemplating a photograph made in 1914 by August Sander. In the essay within the book called The Suit and The Photograph, Berger notes:

The date is 1914. The three young men belong, at the very most, to the second generation who ever wore such suits in the European countryside. Twenty or 30 years earlier, such clothes did not exist at a price which peasants could afford.

Berger arrives at his conclusions based on what he deduces from the photograph, coupled with his knowledge of the geographic location, the date of the photograph, and other extant information, including the body types of those men pictured. He notes, “Their hands look too big, their bodies too thin, their legs too short” for the suits they are wearing. He peels back the photograph to its very essence and draws conclusions about its subjects based on body type, the fit of their clothing, historical data, location, posture, and whatever else he can make out in the space of the black and white image. But what he is looking at is the subject of the photograph, not the veneer of the photograph. He is not critiquing the style or the technique of the object before him, rather, he has separated the “content” from the container, as if to discard the wrapper to get to what is inside. It is the most hermeneutic response to a work of art one can imagine yet tells us much about those inhabiting the space of the photograph, if in an anthropological way.

Berger arrives at his conclusions based on what he deduces from the photograph, coupled with his knowledge of the geographic location, the date of the photograph, and other extant information, including the body types of those men pictured. He notes, “Their hands look too big, their bodies too thin, their legs too short” for the suits they are wearing. He peels back the photograph to its very essence and draws conclusions about its subjects based on body type, the fit of their clothing, historical data, location, posture, and whatever else he can make out in the space of the black and white image. But what he is looking at is the subject of the photograph, not the veneer of the photograph. He is not critiquing the style or the technique of the object before him, rather, he has separated the “content” from the container, as if to discard the wrapper to get to what is inside. It is the most hermeneutic response to a work of art one can imagine yet tells us much about those inhabiting the space of the photograph, if in an anthropological way.

Berger wrote his essay in 1980, premised on Jacques Derrida’s ideas about deconstruction which had recently taken hold of the arts, especially the arts in academic settings. I attended art school in the 1980’s and the practice that Berger undertakes in The Suit and The Photograph is so deeply imprinted in the way that I respond to works of art that, at times, it does not occur to me there is another way of apprehending such works. However, there are times when, if lucky, I am struck by something unexpected, something uncanny that registers in some other way, before the part of my brain that begins to deconstruct my experience kicks in.

I had such an experience recently with a sculpture by the Italian artist Giuseppe Pennone called Idee di pietra (Ideas of Stone). It was simply a tree with a boulder stuck in its canopy of branches, leaves fallen away and standing in an open space between academic buildings on the campus of Brown university. Quite unremarkable, except that it wasn’t. The shock of the unexplainable physics of the image I happened upon interrupted my understanding of the world and forced me to stop and consider what I had happened upon. While the tree turned out to be a cast replica of a tree, the boulder was indeed real. Pennone is a member of the post-war Italian movement Arte Povera, a term that was originally coined by the art critic Germano Celant. Celant was attempting to describe the activities of Italian artists who used the simplest of materials and methods to create poetic statements based on everyday life; a humanist movement that mirrored minimalism in some ways but ascribed a gestural presence with much of their work. For the artists of Arte Povera, art could be made from anything: immaterial substances such as moisture, energy, or sound, or living things, natural and/or industrial materials. These trends toward a kind of human scale art practice in which the artist’s body was central to the reading of such works crosses all disciplinary boundaries from painting and sculpture through photography and performance, and is still relevant for any contemporary artist’s practice. Arte Povera produced some of the most iconic objects in the post-war era, ranging from simple provocations to highly metaphoric evocations of humanness.

I had such an experience recently with a sculpture by the Italian artist Giuseppe Pennone called Idee di pietra (Ideas of Stone). It was simply a tree with a boulder stuck in its canopy of branches, leaves fallen away and standing in an open space between academic buildings on the campus of Brown university. Quite unremarkable, except that it wasn’t. The shock of the unexplainable physics of the image I happened upon interrupted my understanding of the world and forced me to stop and consider what I had happened upon. While the tree turned out to be a cast replica of a tree, the boulder was indeed real. Pennone is a member of the post-war Italian movement Arte Povera, a term that was originally coined by the art critic Germano Celant. Celant was attempting to describe the activities of Italian artists who used the simplest of materials and methods to create poetic statements based on everyday life; a humanist movement that mirrored minimalism in some ways but ascribed a gestural presence with much of their work. For the artists of Arte Povera, art could be made from anything: immaterial substances such as moisture, energy, or sound, or living things, natural and/or industrial materials. These trends toward a kind of human scale art practice in which the artist’s body was central to the reading of such works crosses all disciplinary boundaries from painting and sculpture through photography and performance, and is still relevant for any contemporary artist’s practice. Arte Povera produced some of the most iconic objects in the post-war era, ranging from simple provocations to highly metaphoric evocations of humanness.

In those moments when I am surprised by a work of art, indeed disarmed by it, I feel most human.

Douglas Rosenberg

Chair, UW-Madison Art Department