“No, what’s your real name?”

[Professor of Glassworking] Helen Lee was chatting with her taxi driver, a man from Ethiopia, when he asked the question. He’d sensed something the two of them shared, a custom in immigrant families – as she puts it, “You have an American name, and then another name.” Her Chinese name, which means a red cloud before a snowfall, has no direct translation in English. “It’s like a private identity,” says Lee, who later spelled the cabbie’s query in a necklace.

Lee has lived much of her life in translation. The daughter of professionals from Taiwan (her father was an electrical engineer, her mother a computer programmer), she was born in New Jersey and grew up bilingual, speaking a hybrid “Chinglish” at home. Her grandmother, who raised her while her parents worked, spoke only Mandarin. When it came to interacting with the outside world or even just watching TV, it was Lee who, from a tender age, helped her grandmother negotiate English-speaking society.

“I spent a lot of time moving between Chinese and English, trying to explain something to my grandmother, or thinking about how she might be thinking about it,” Lee, 39, recalls. In her mind, there existed a zone between those two very different languages and cultures, where connections, both linear and lateral, were made.

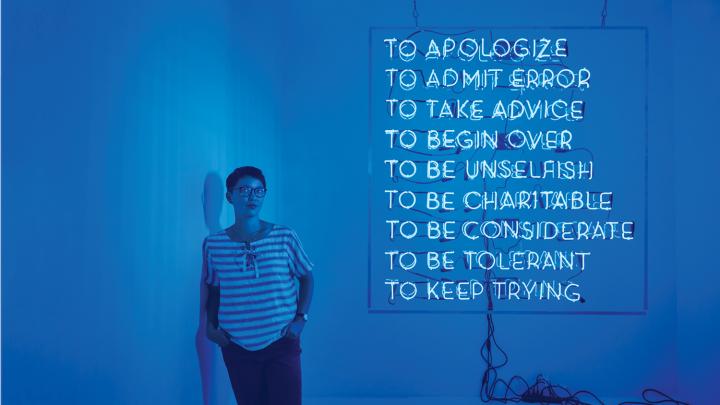

Today, working primarily in glass, Lee draws on that “third space” to make art about language: the emotional power of words, things said and unsaid, and “the weird routes that information takes through translation.” In conversation, ironically, she finds aspects of her work hard to articulate, but her pieces express the ineffable in sublime form, inviting us to consider how we perceive words, gestures, signs, and signals.