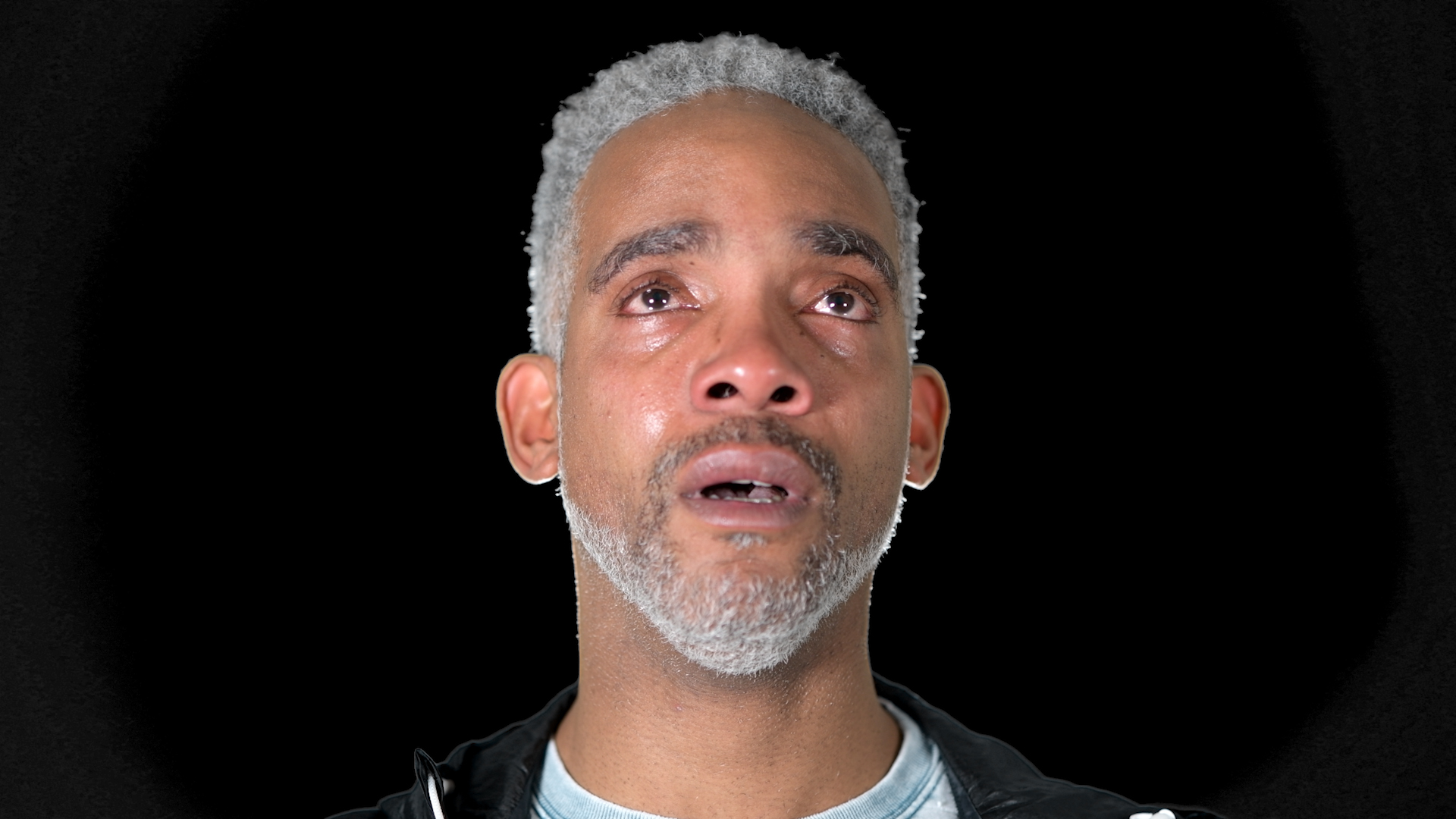

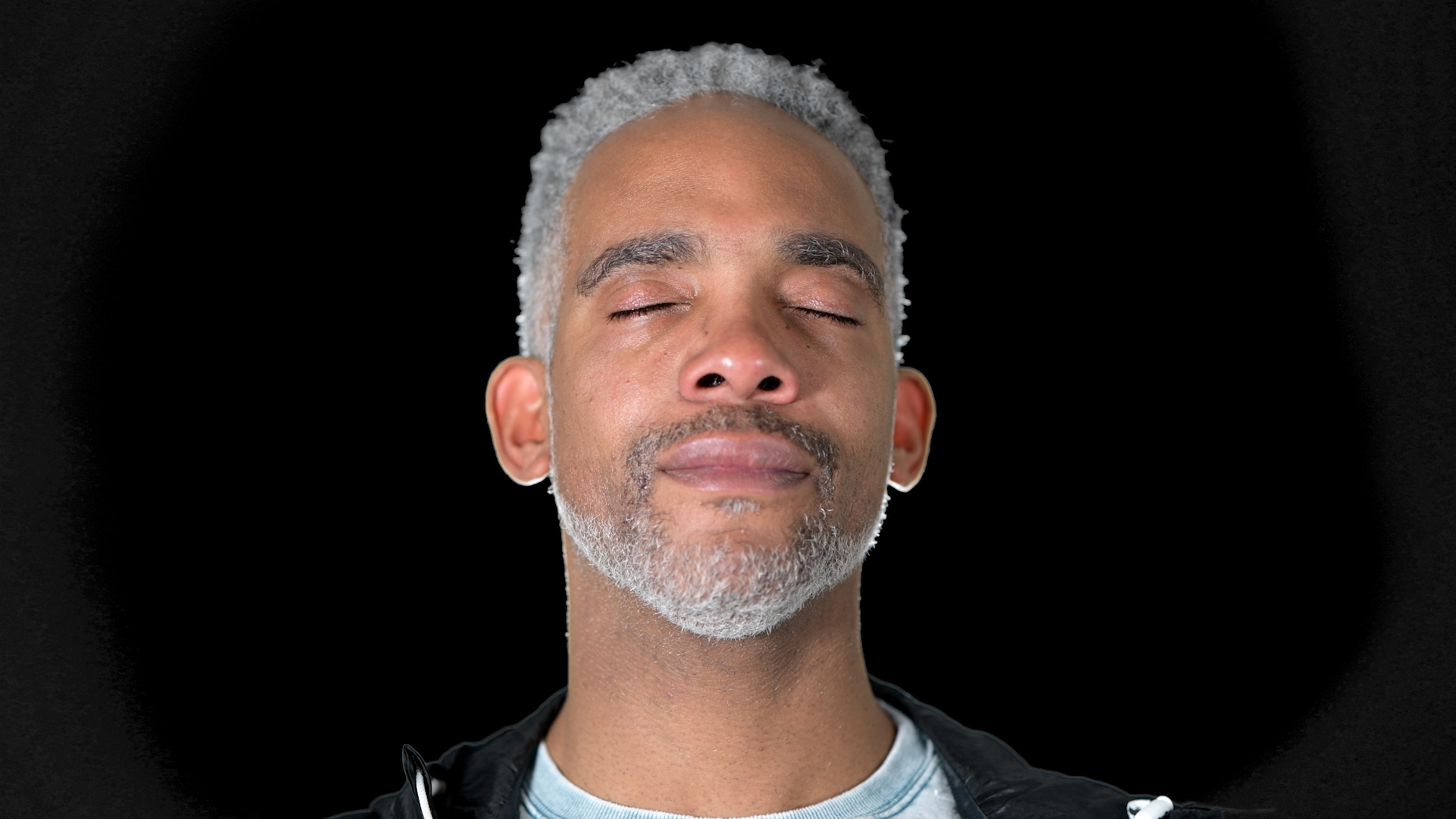

Anwar Floyd-Pruitt

4D, MFA ’20

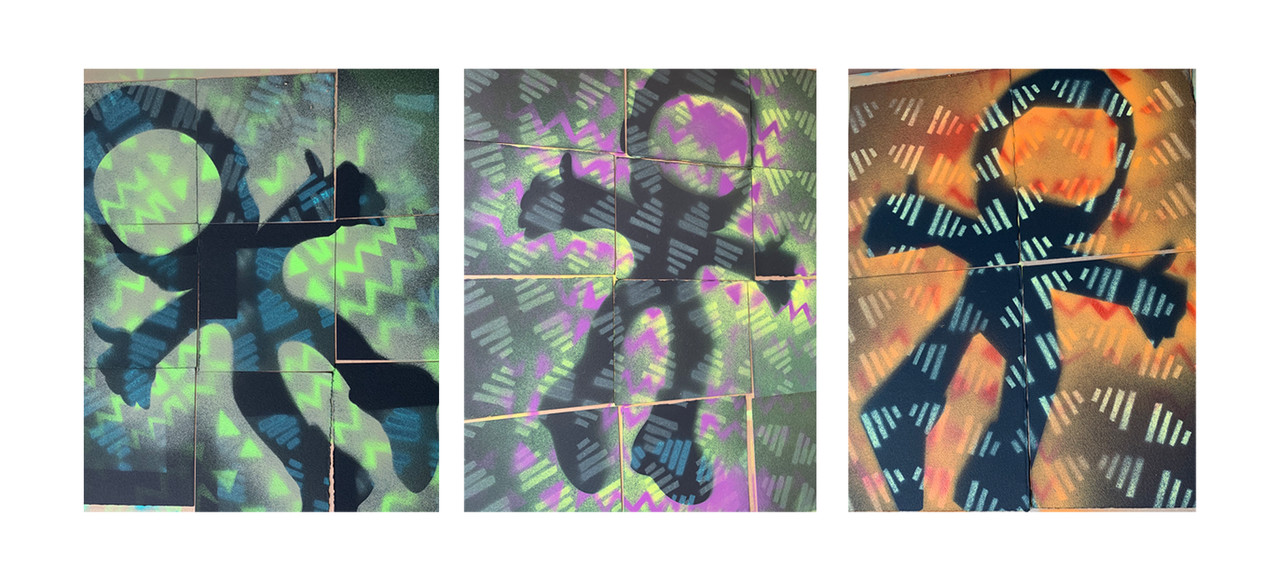

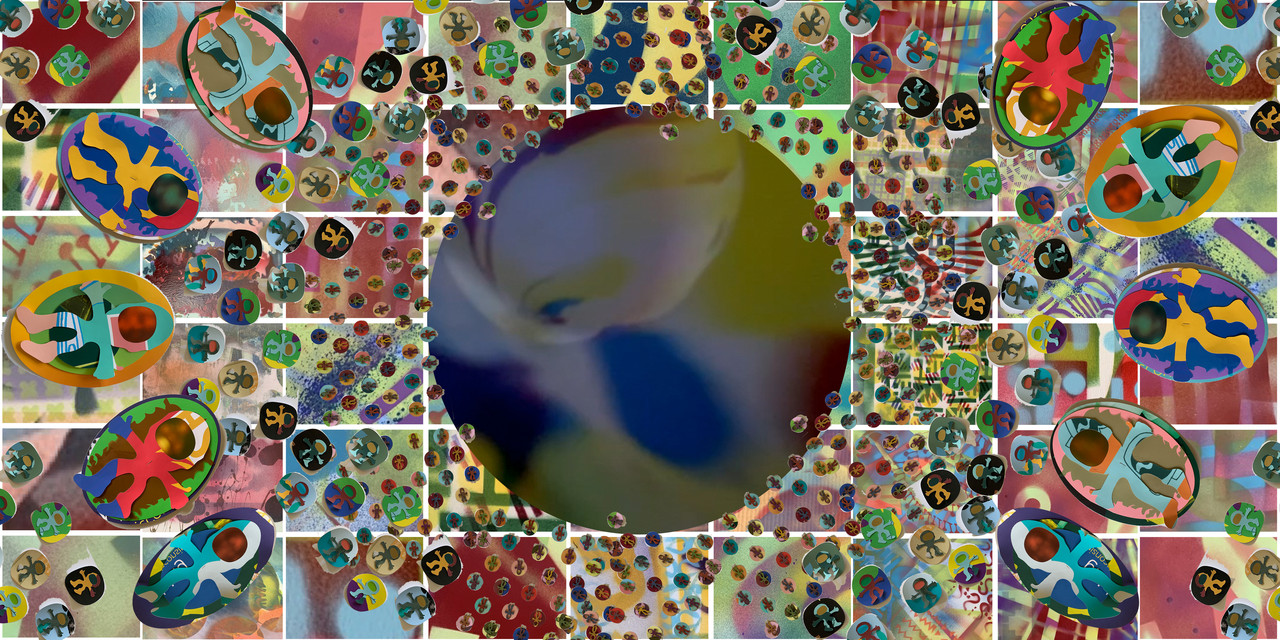

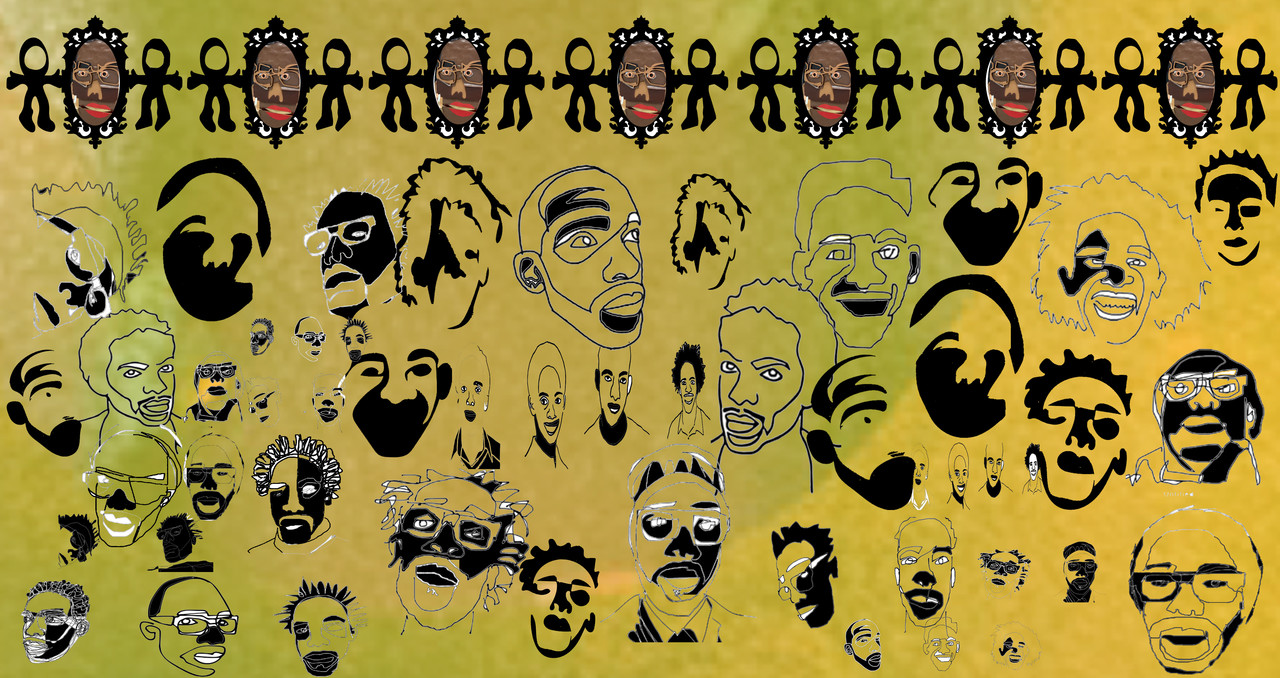

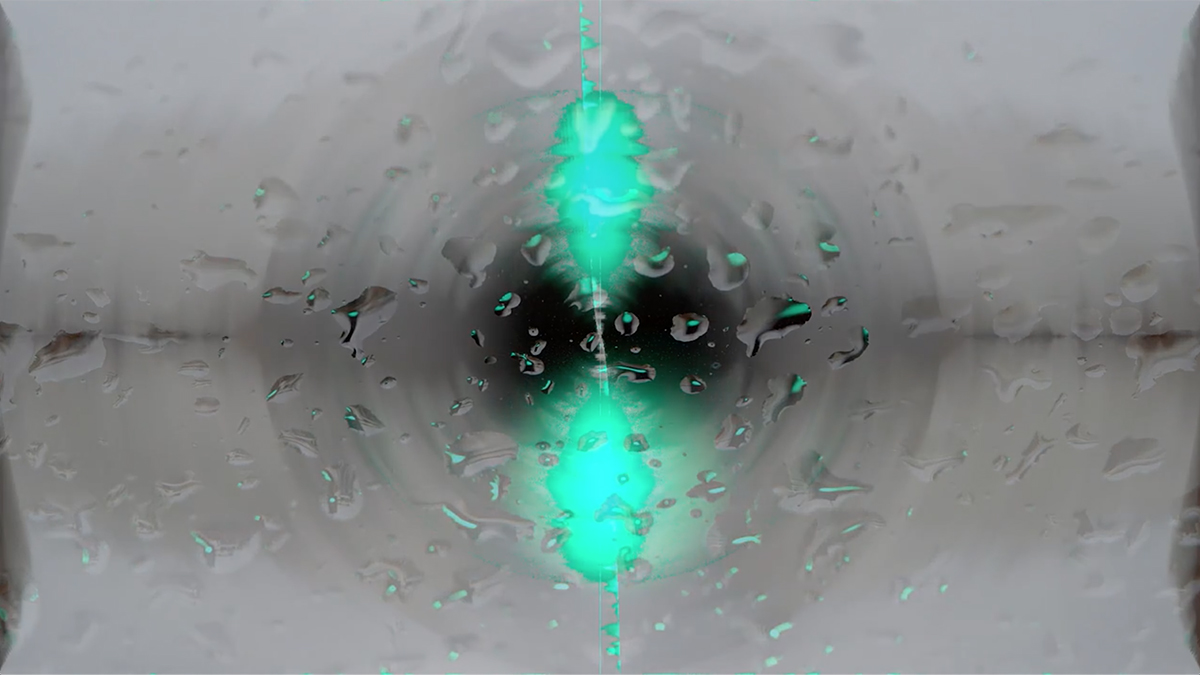

SUPERNOVA: Charlotte and Gene’s Radical Imagination Station

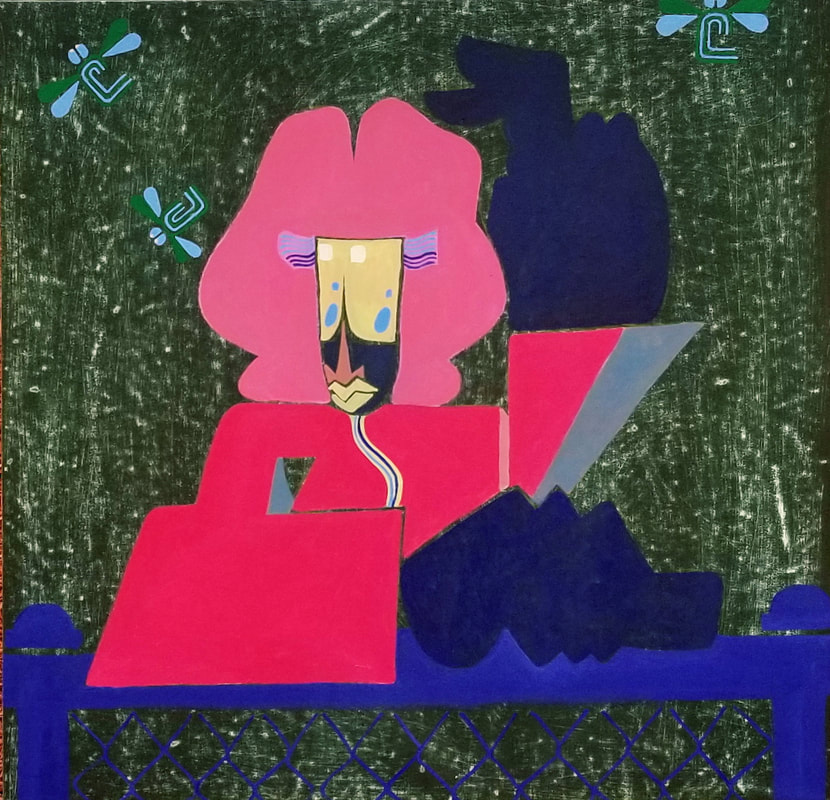

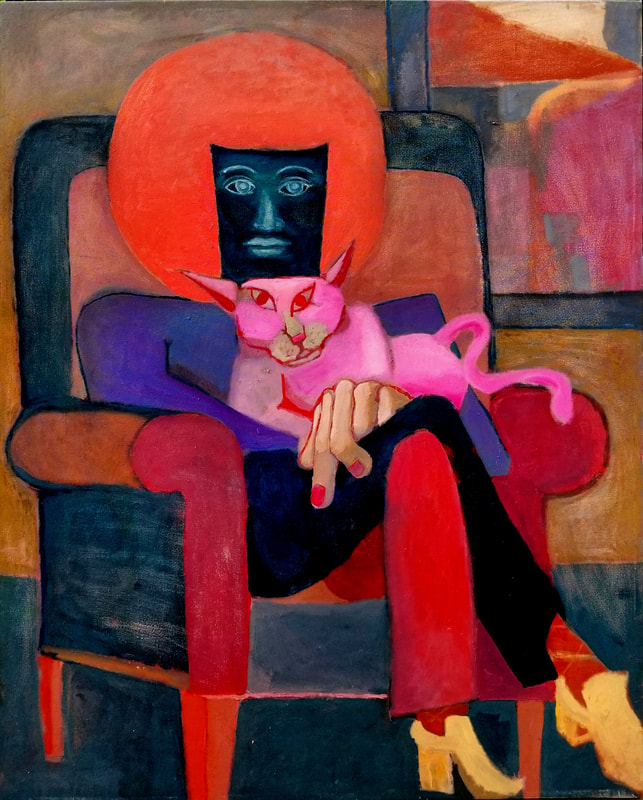

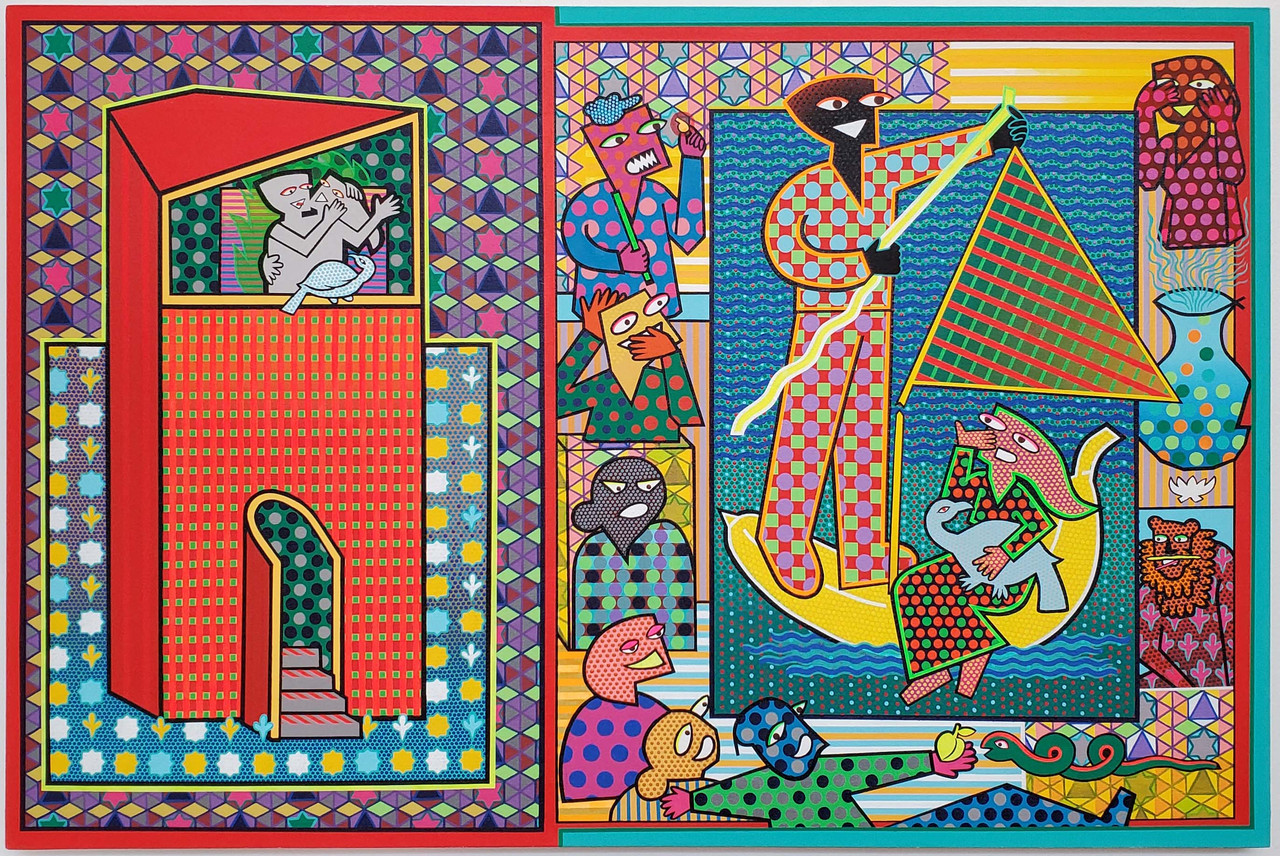

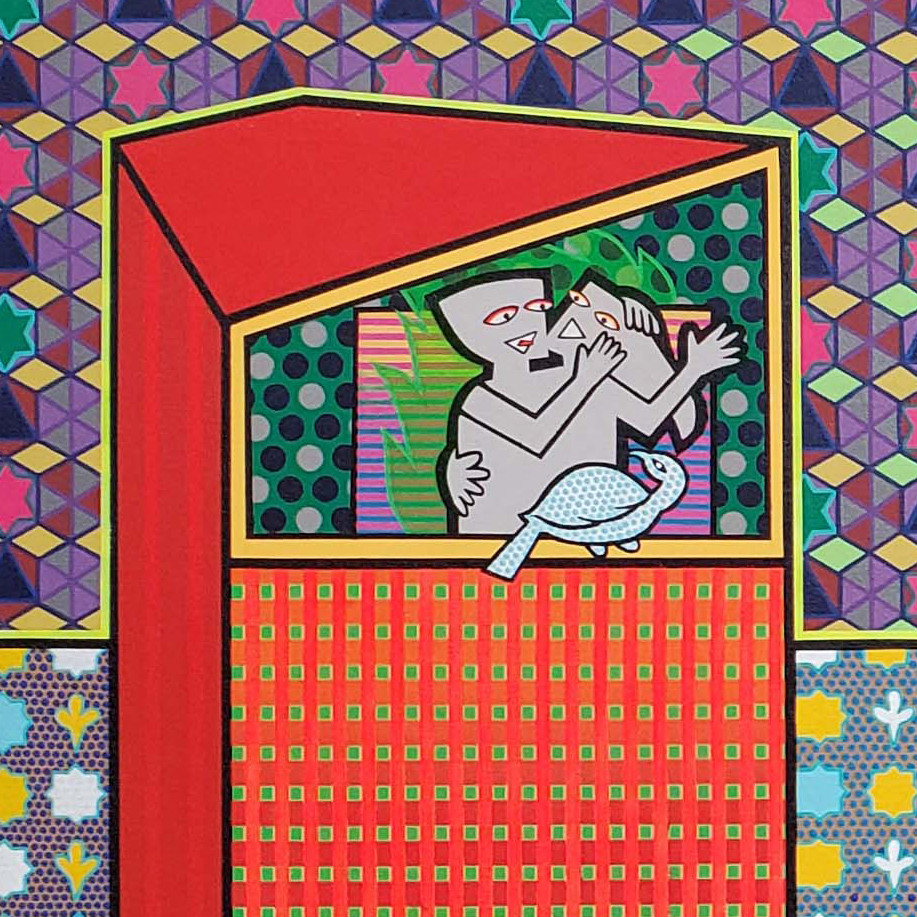

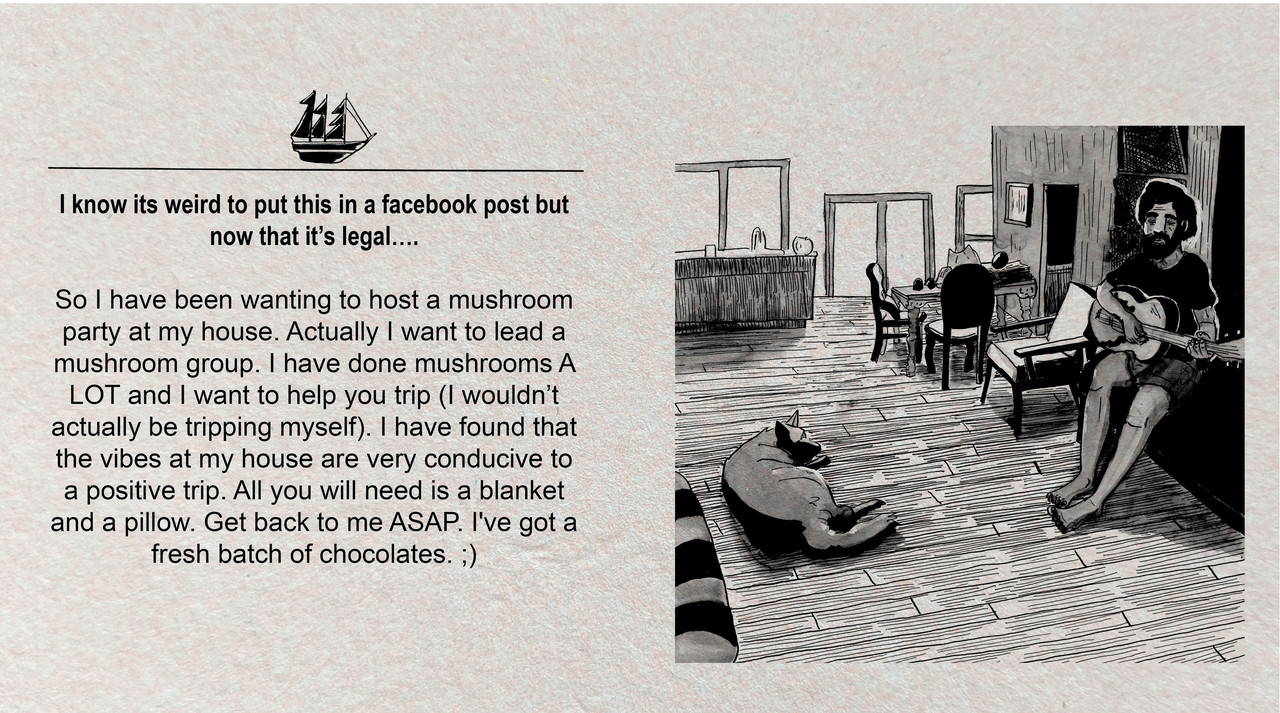

Supernova: Charlotte and Gene’s Radical Imagination Station is a self-portrait, a family memoir, and an Afrofuturist fantasy ode to the title characters, my parents, who, have always encouraged me to pursue my passion and live my dreams.

The exhibition envisions Charlotte and Gene as baby astronauts, embarking on an interstellar adventure to find each other, to find me, and to find my younger siblings. An ornately-framed mirror from my childhood home serves as a vehicle for space exploration and time travel, where the speed of light slows to a moment of reflection, recognition, and contemplation, where one can peer over the precipice of this very moment and decide to dive into the work of reexamining and reframing the past, remembering those on whose shoulders we stand, resituating oneself in the present, and rehearsing for the future.

Colorful patterning blends design motifs from the home, visual elements of my DNA spectrometer analysis and satellite views of the cosmos, creating a vast tableau and ground for vignettes of my family’s adventures. The self-portraits are amalgamations of images and modes of reproduction, remixing my grandparents and my parents to create a multiverse of Me.

Reflections, refractions, and abstractions intermix into a layered, multimedia installation, recount the influence of my ancestors, narrate my parents’ life stories, and propose an open-ended future of our own creation.

I love you mom and dad. You are the brightest stars in my universe.

Anwar Floyd-Pruitt is the Chazen Museum of Art 2020 Russell and Paula Panczenko MFA Prize winner. Awarded to one graduating MFA candidate from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, the annual Chazen Prize exhibition prize is offered in collaboration with the Art Department and judged by an outside visiting curator. Renowned curator, author, and historian Glenn Adamson selected this year’s recipient. Floyd-Pruitt’s prizewinning MFA thesis exhibition will be shown at the Chazen Museum, which has been postponed until this fall.

Eleanor Rose Meineke

Woodworking, MFA ’20

Lilium

Eleanor began her career as a toolmaker and although toolmaking continues to be an essential part of her practice, her life and work have changed drastically over the last year. Eleanor recently came out as a trans woman. Coming out was liberating; a literal rebirth, but also an opportunity to establish, publicly, an identity that lay dormant since childhood. Her work explores this process through a surrealist approach to historical furniture, particularly deconstruction of the Windsor chair. Through unlikely juxtapositions and exaggerated proportions, she imbues her objects with the same sense of wrongness she felt for decades while living in a male body.

Ashley Lusietto

Painting & Drawing, MFA ’20

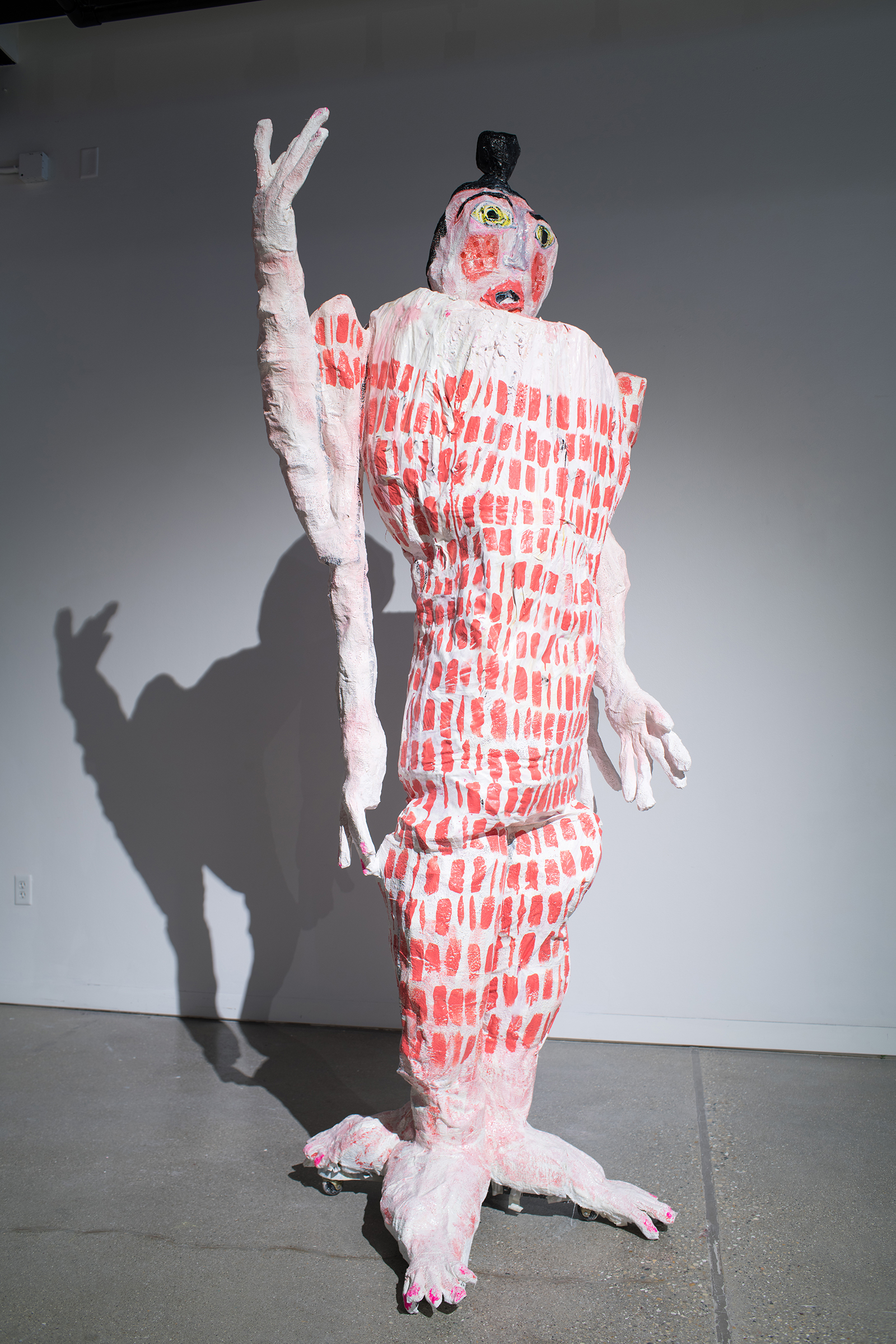

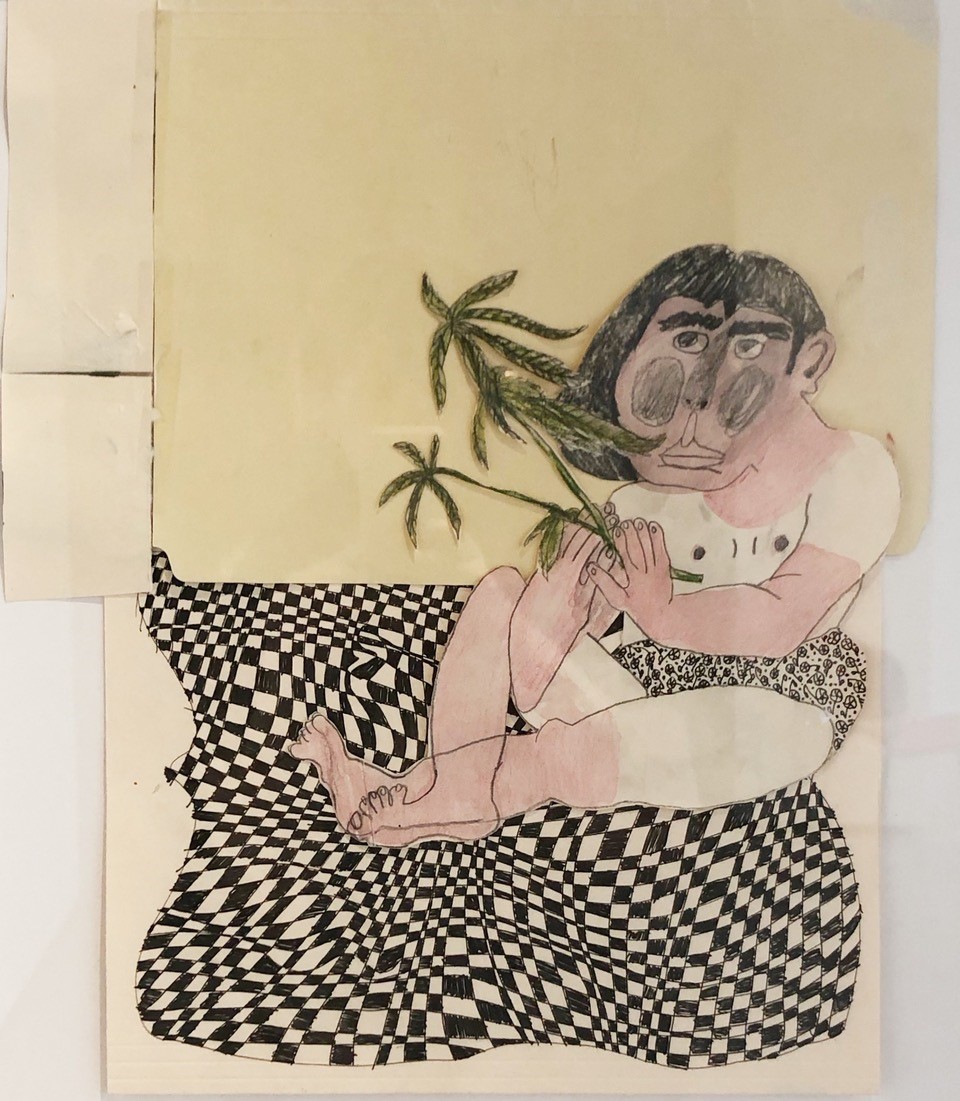

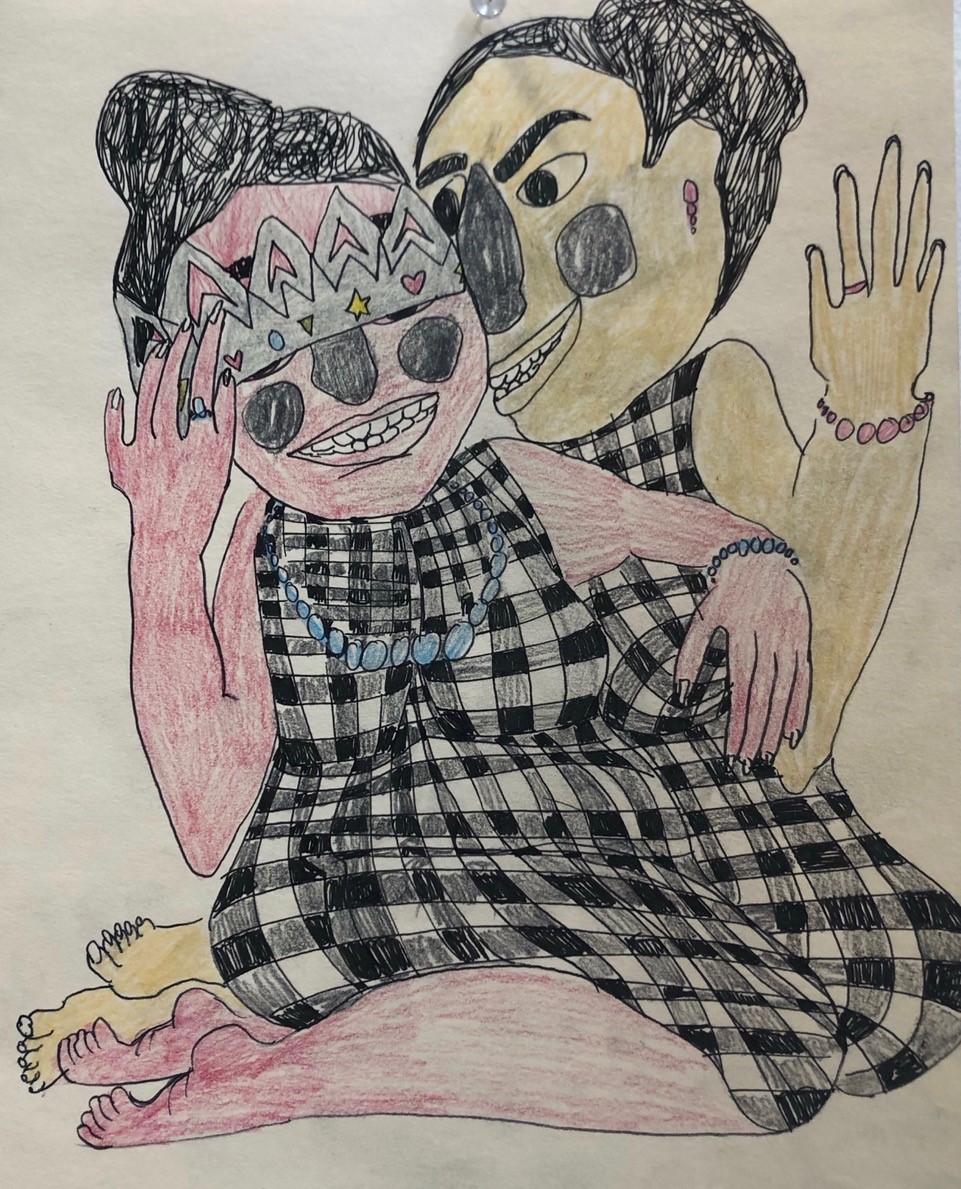

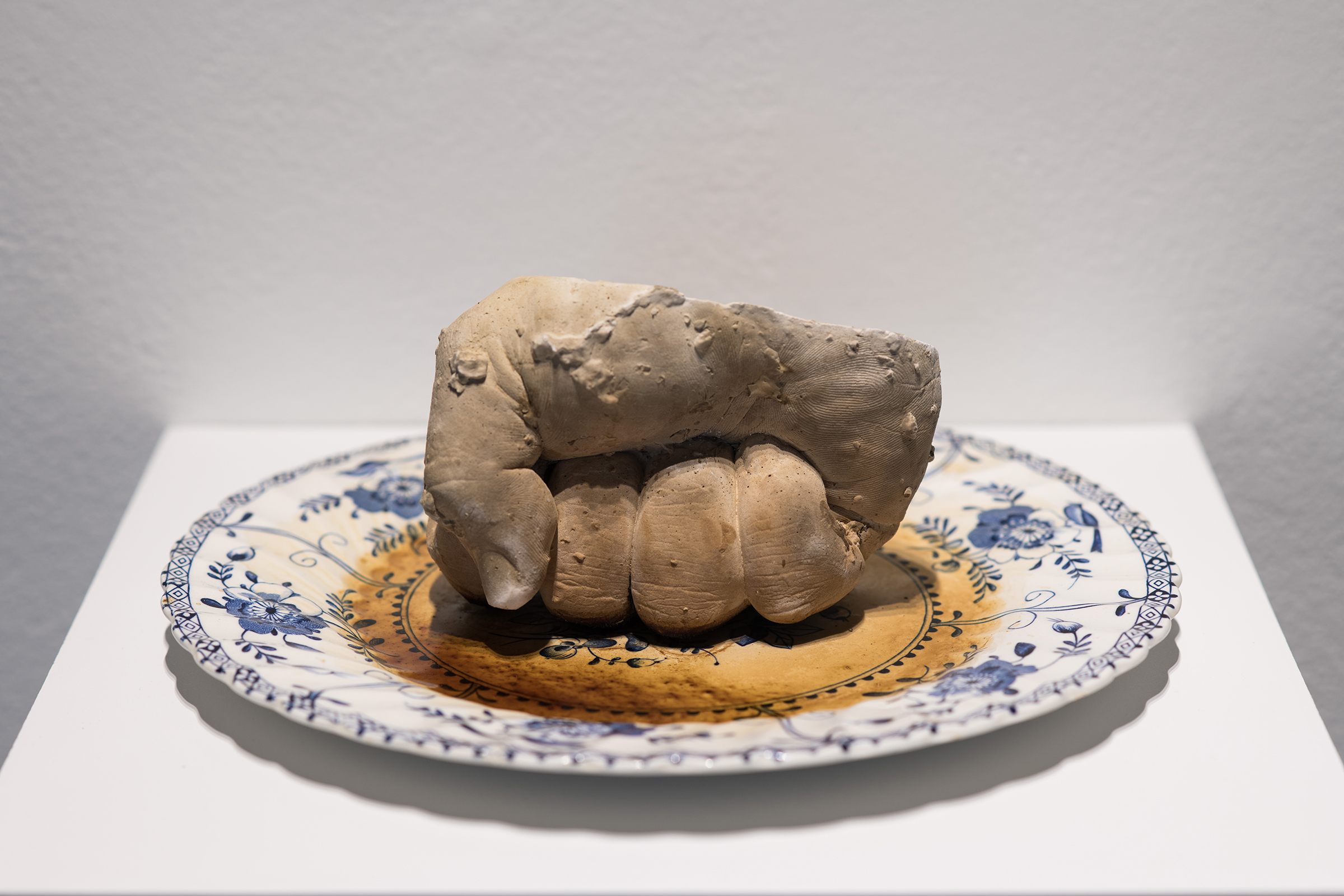

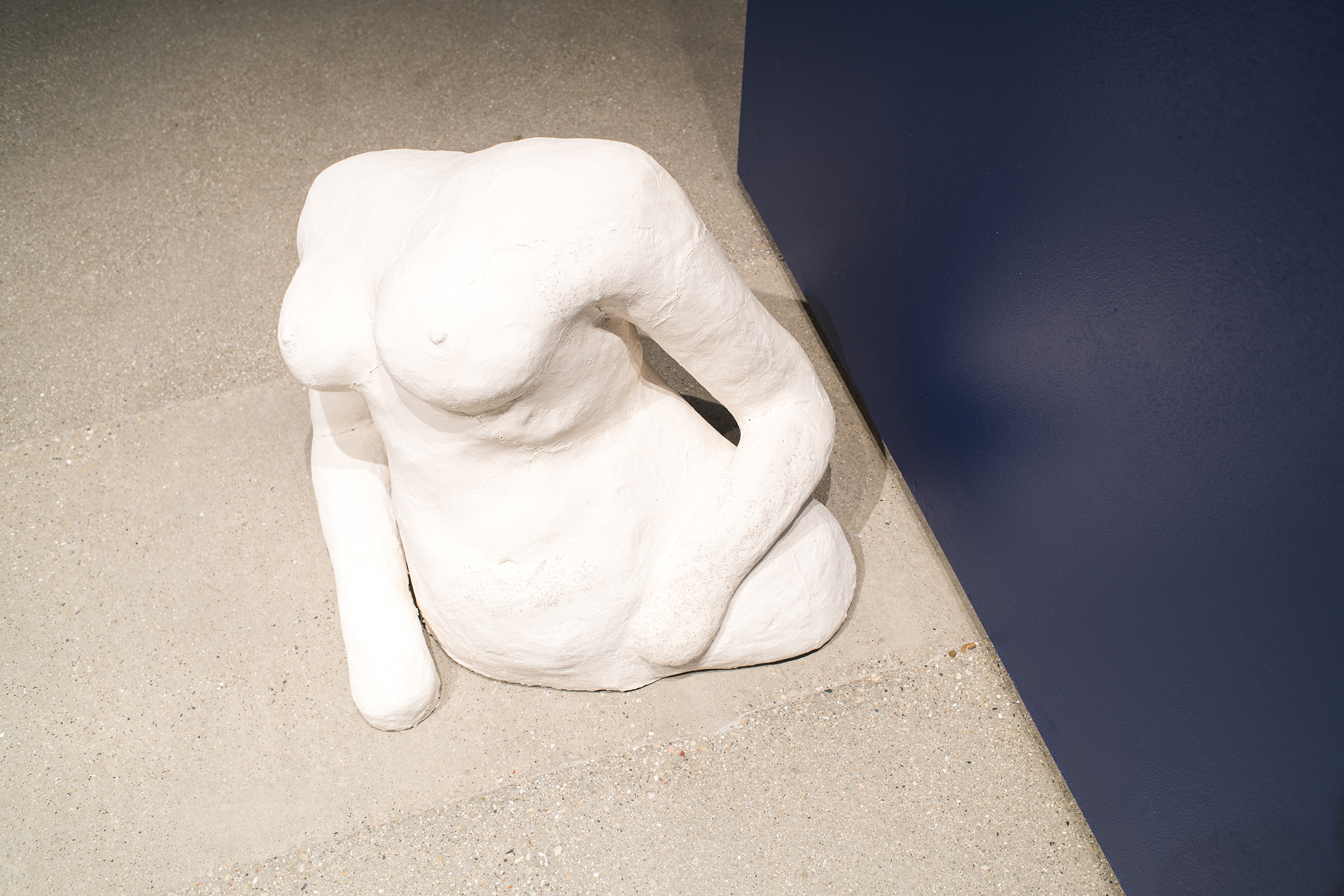

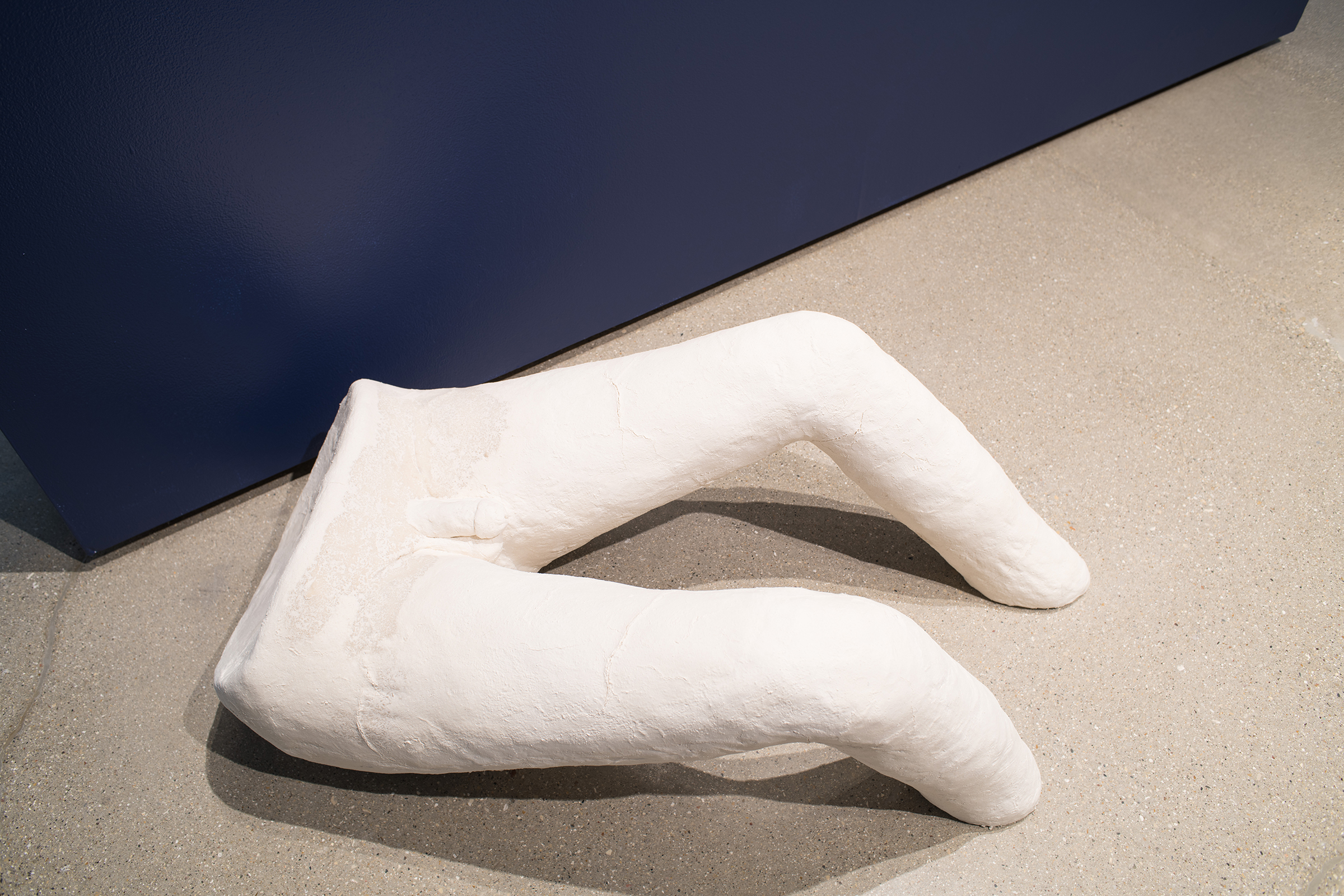

Fell Into the Honey

Working from autobiographical content, I exchange factual representations of people and events for my own fantastical reinterpretations. Mythologizing my personal history fulfills a desire to reclaim the past with a sense of authority and commitment to the truth of my emotions. Through processes in painting, drawing, and sculpture I use color and material to embed tones of joy and anxiety—the mixed feelings of remembering. The figuration of my work—divine, maternal, animalistic, childlike, etc.—emerges from a practice of making self-portraits and alter egos. My characters with their exaggerated bodily features, garishly made-up faces, and exposed meaty flesh, are vulnerable, emotional, and direct.

In my MFA exhibition Fell Into the Honey, I found inspiration in ancient funerary processes, The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, and the memory of receiving a box of brand new dolls in the mail as a child. Fell Into the Honey makes a twisted fairytale of my slow-burning nostalgias, set in a fantasy where the characters playfully blur the lines of alter-ego, inner child, feminine divine, and self-portrait. In my cathartic reimagining of a lingering childhood, death becomes a catalyst for healing and preservation. To “fall into the honey” is euphemistic for dying. That sickly sweet liquid amber with its eternal shelf-life has been used for thousands of years in burial practices. Ancient honey-embalmed corpses laid to rest in tombs remain well preserved today. In my work I use honey metaphorically—to sweeten the taste of bitter remembering and to embalm the selves of the past.

Yoshinori Asai

4D, MFA ’20

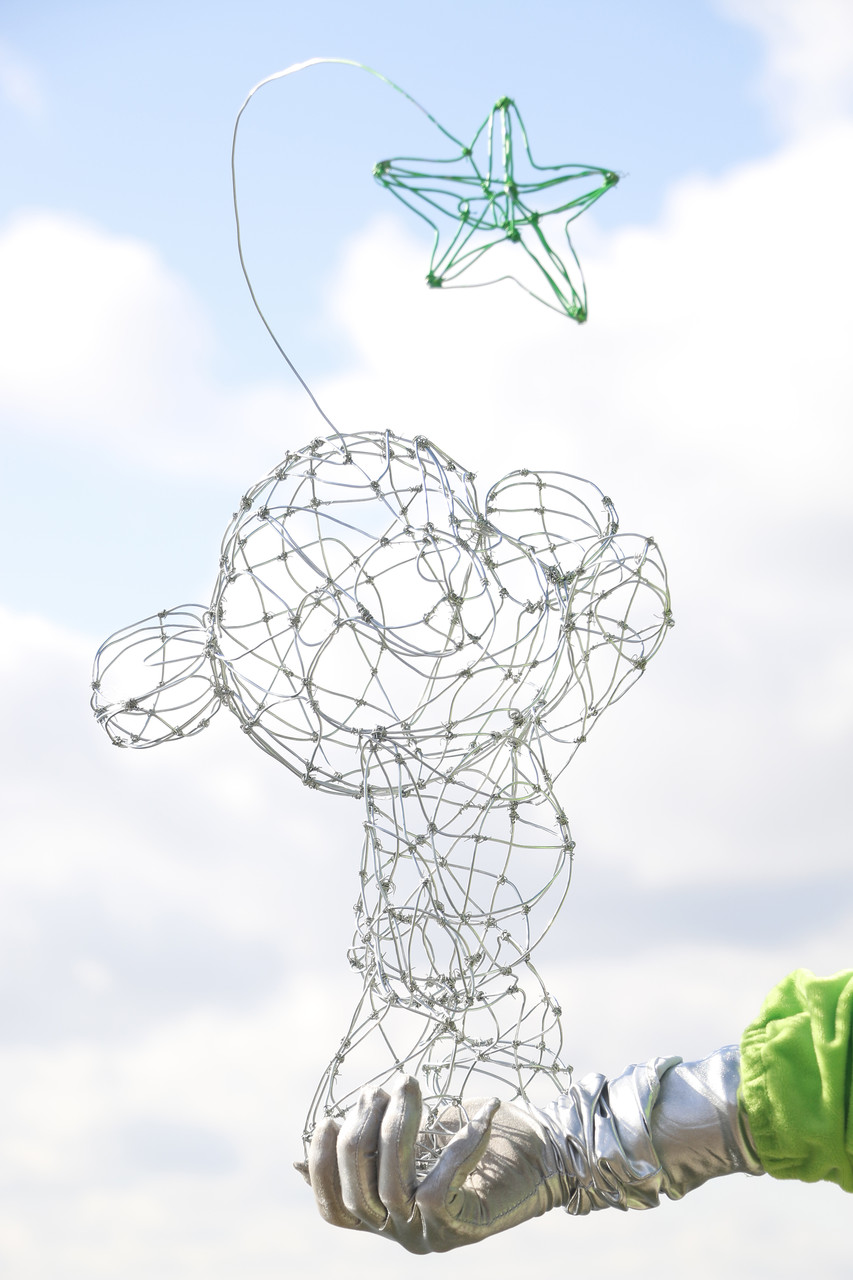

Unidentifiable Friendly Objects

I see my existence in this physical world as a balancing act. It shakes when one is unbalanced. Sometimes, it’s more stable. Yet, regardless, it’s always in flux. I see this movement itself as life. The movement begins from seemingly out of nowhere and it will eventually come to an end.

There is a Japanese proverb that states, “a soul of three is carried to a hundred.” I interpret this as meaning: whoever we are at a young age, we carry this person with us until we die. When I feel unbalanced, I often find that the cause stems from my childhood. Balancing in the in-between states of sexuality, nationality, pushing limits of normality, or even morality… the consistent wave of questions keep coming at me in my head and I lose balance as I reach for answers. Perhaps a reconsideration of our youth can be the key to find a balance in life. In Unidentifiable Friendly Objects, I am engaging many ideas I have absorbed in the course of my life in an attempt to achieve a greater sense of equilibrium or balance.

The objects I’ve created draw on my memories of childhood toys, animals, and cartoon characters to reclaim questions formed long ago. These objects become a sort of neutralizer or bridge between various issues which are the source of my confusion and are pertinent to me as a grown man in that they represent the sense of wonder I am attempting to reclaim from my childhood. By holding them while carrying on, I meditate on and bring my focus to the present moment in order to regain a state of balance.

The exhibition was originally conceived as happening in a physical space with the participation of collaborating performers. However, it eventually became a video piece so I could share it online due to the university shutdown caused by the Coronavirus pandemic. While wandering around an empty Madison, I felt that I was a part of a gigantic international balancing act with so many other humans, struggling to find balance in this unstable world. Using this as an opportunity to reflect and make art has somehow given me that balance, and a sense of calm.

Derek Hibbs

Printmaking, MFA ’20

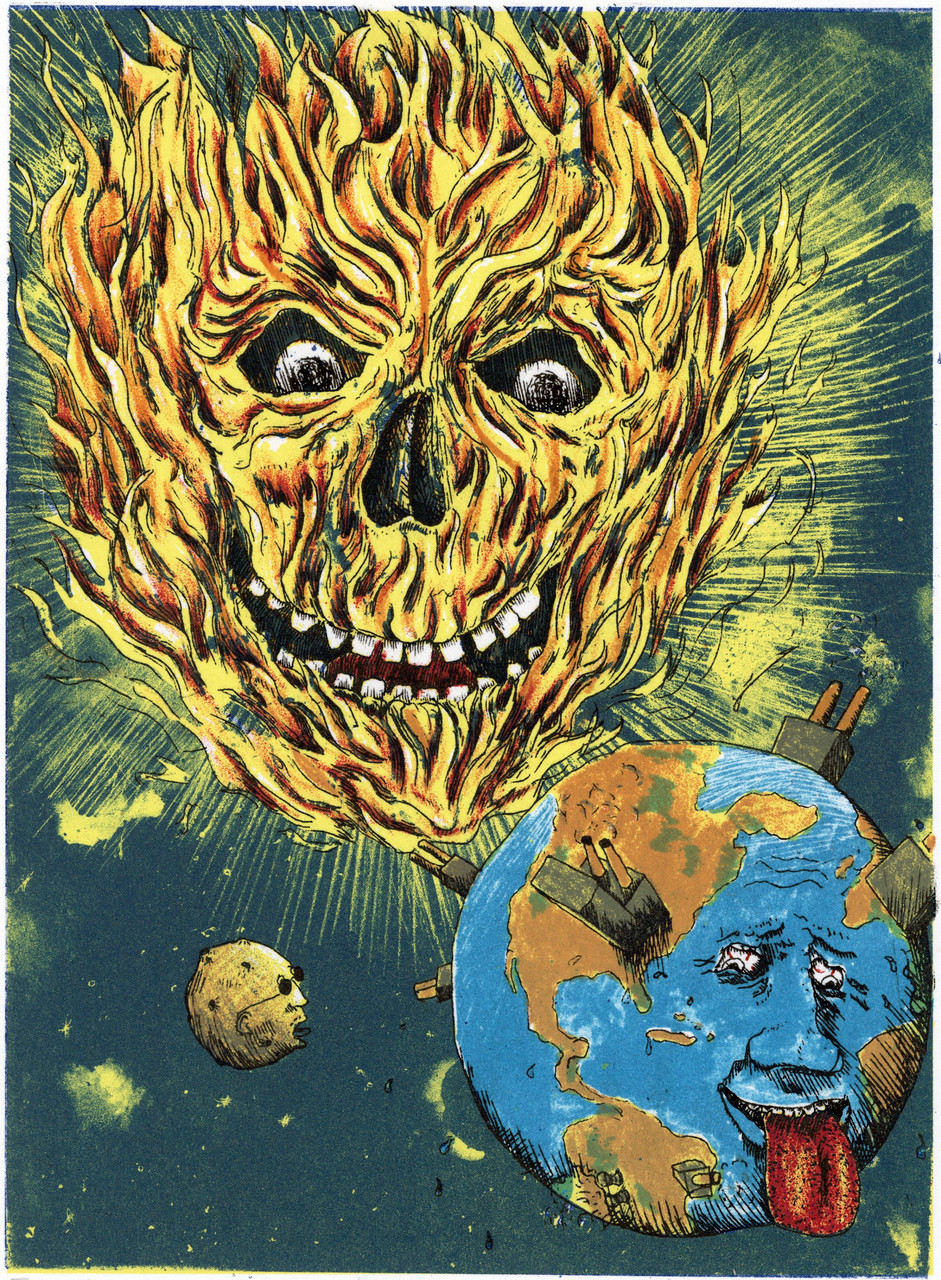

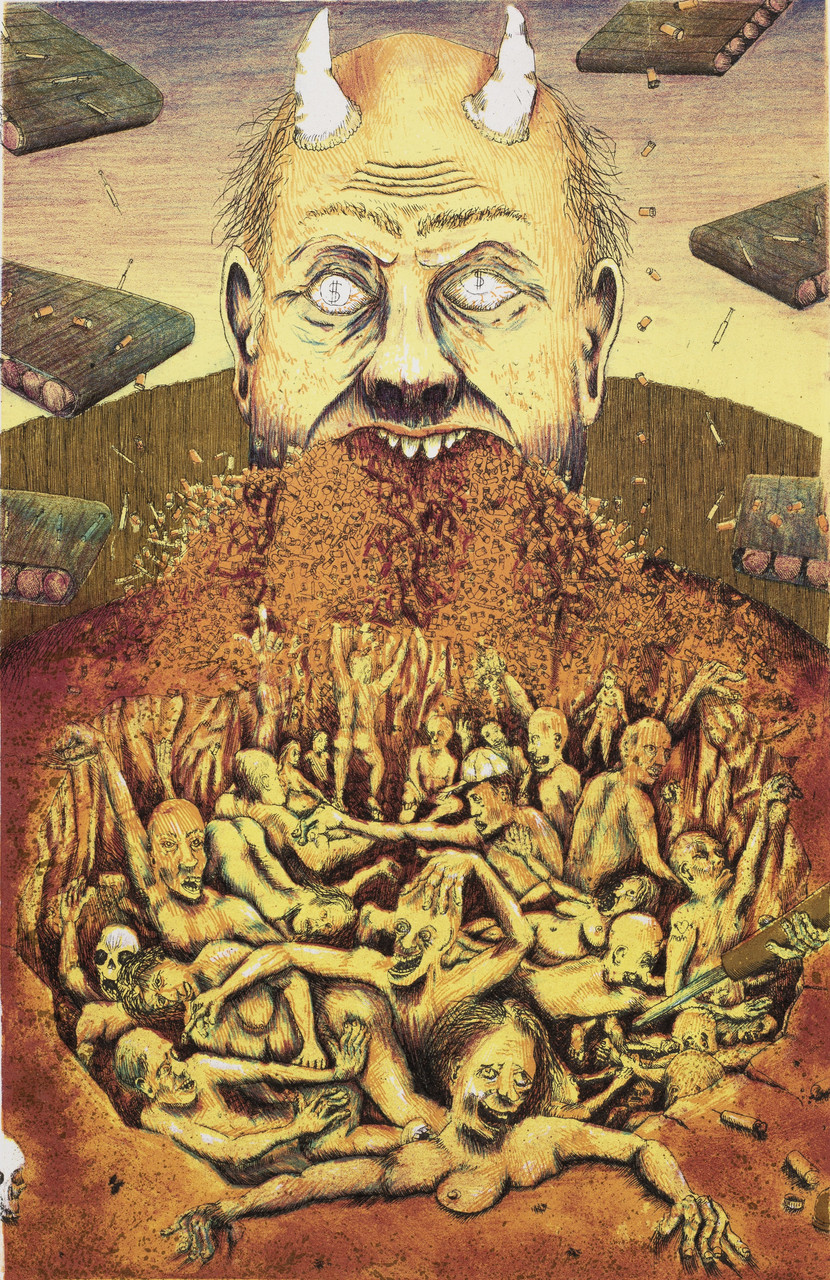

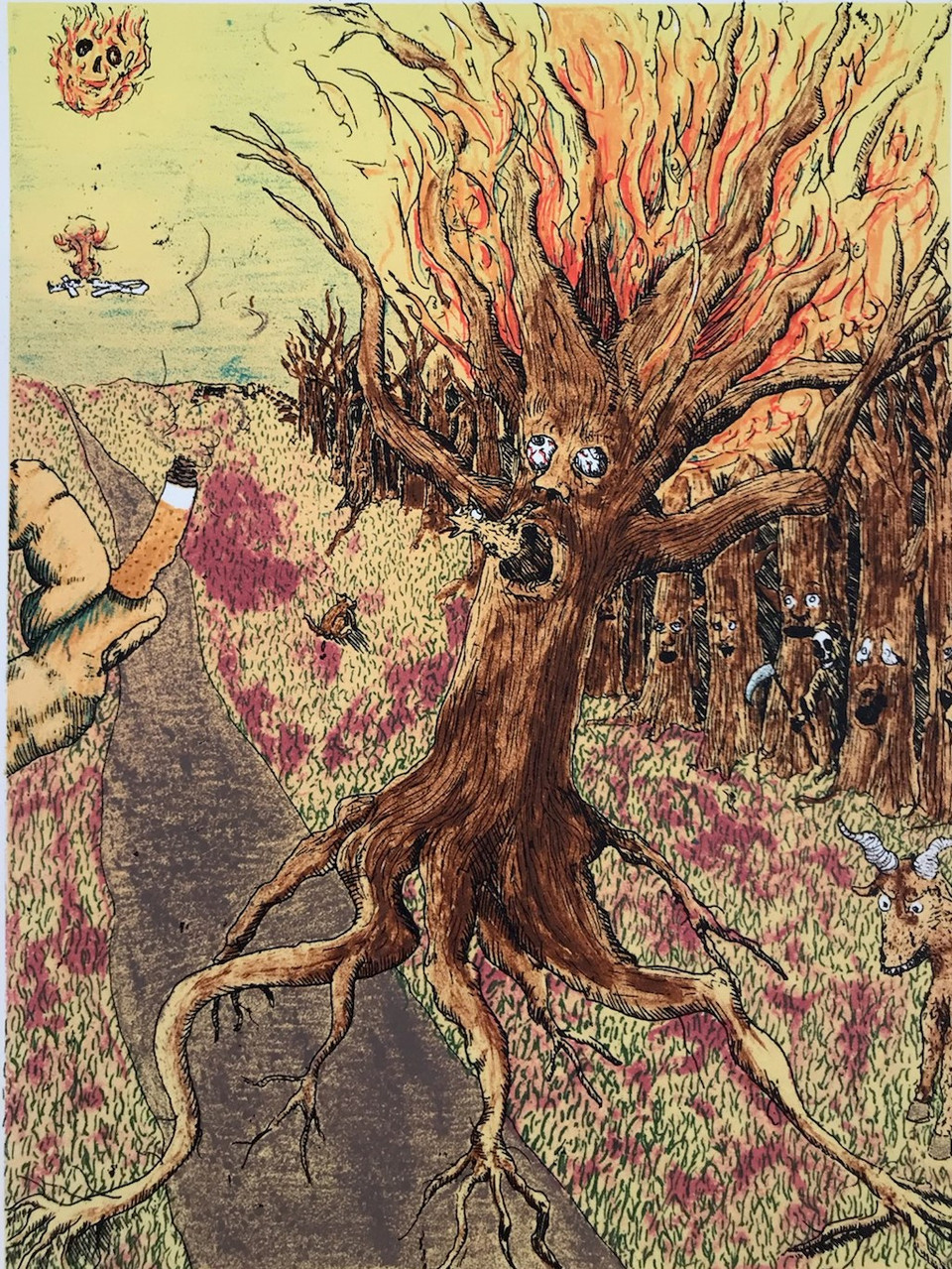

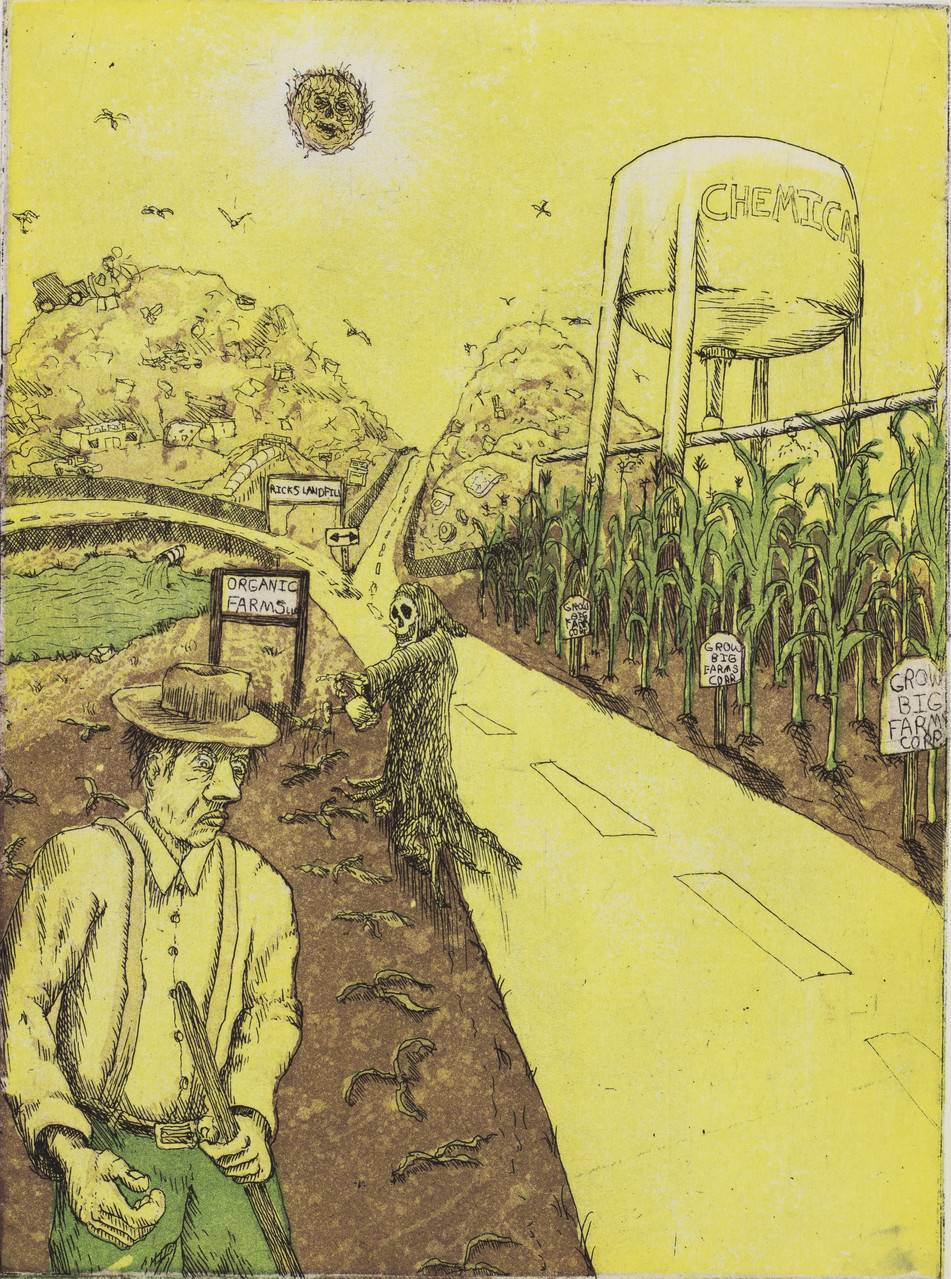

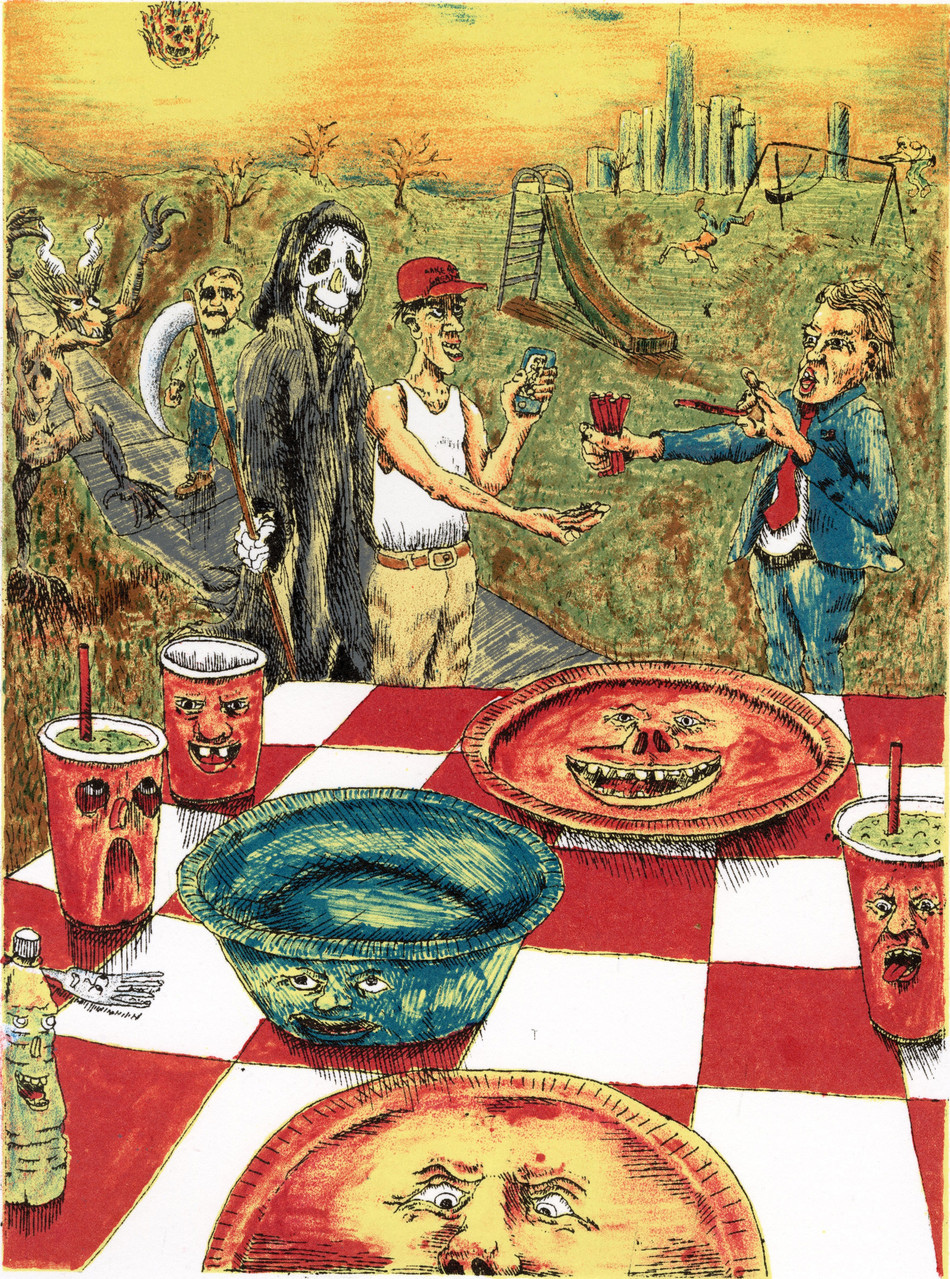

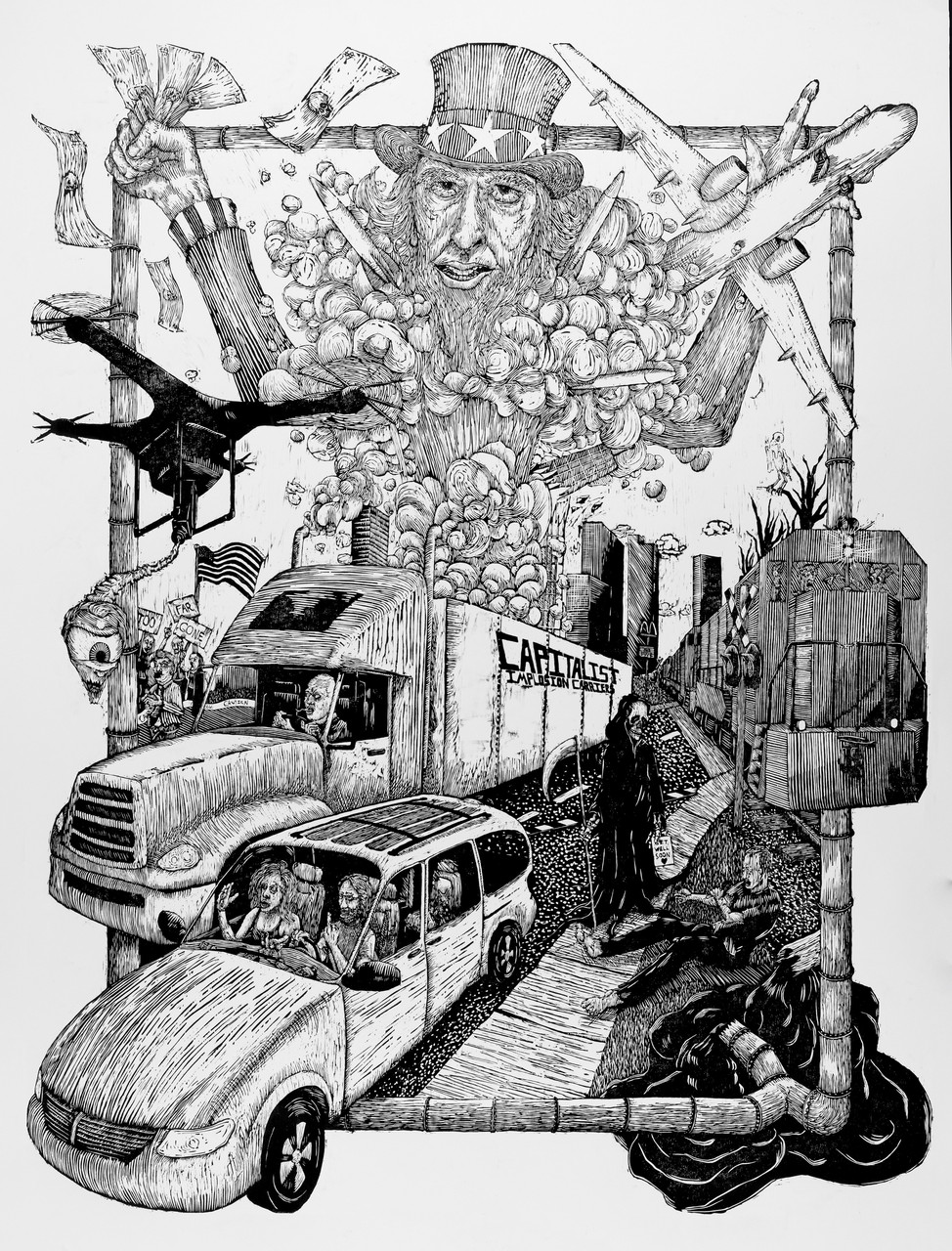

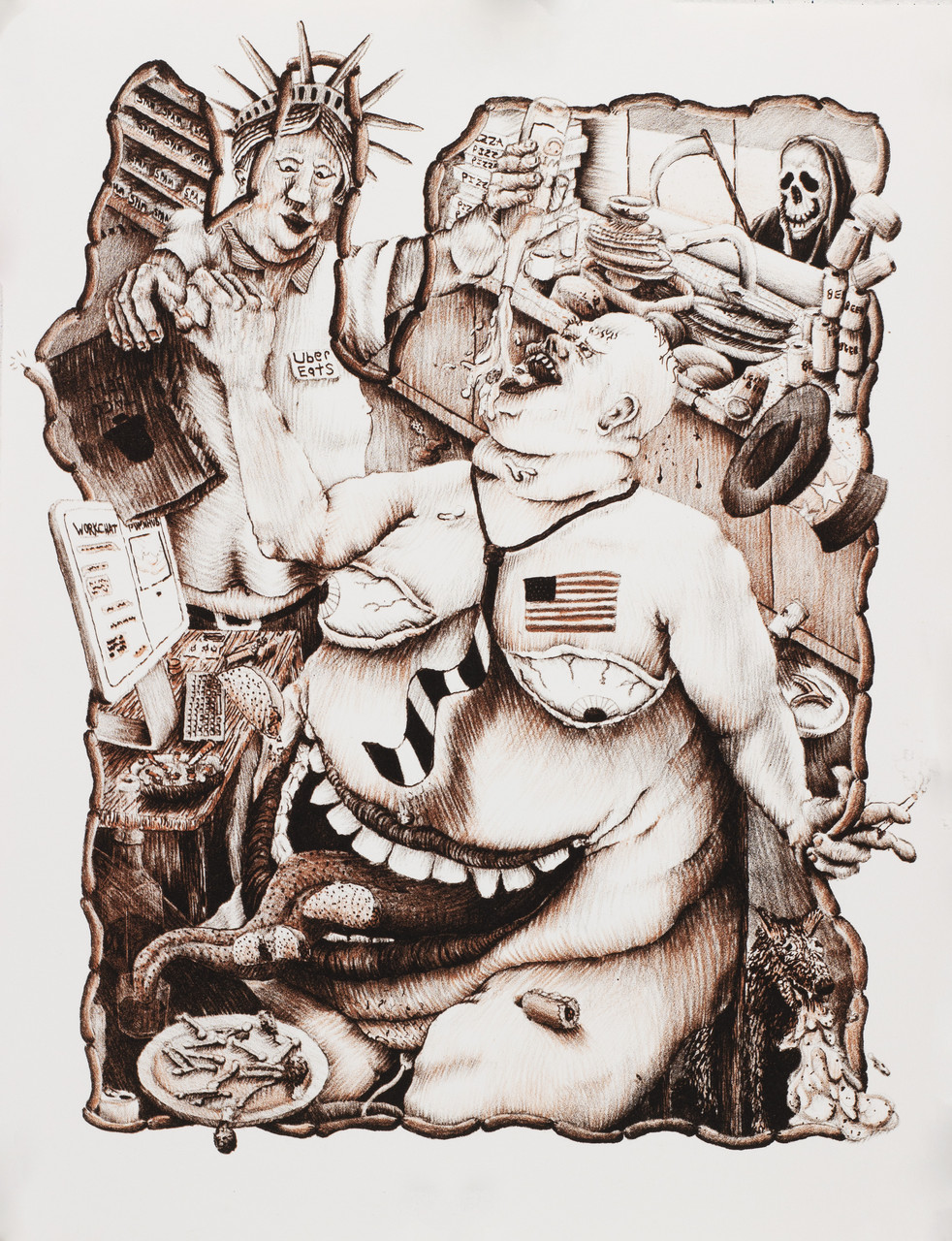

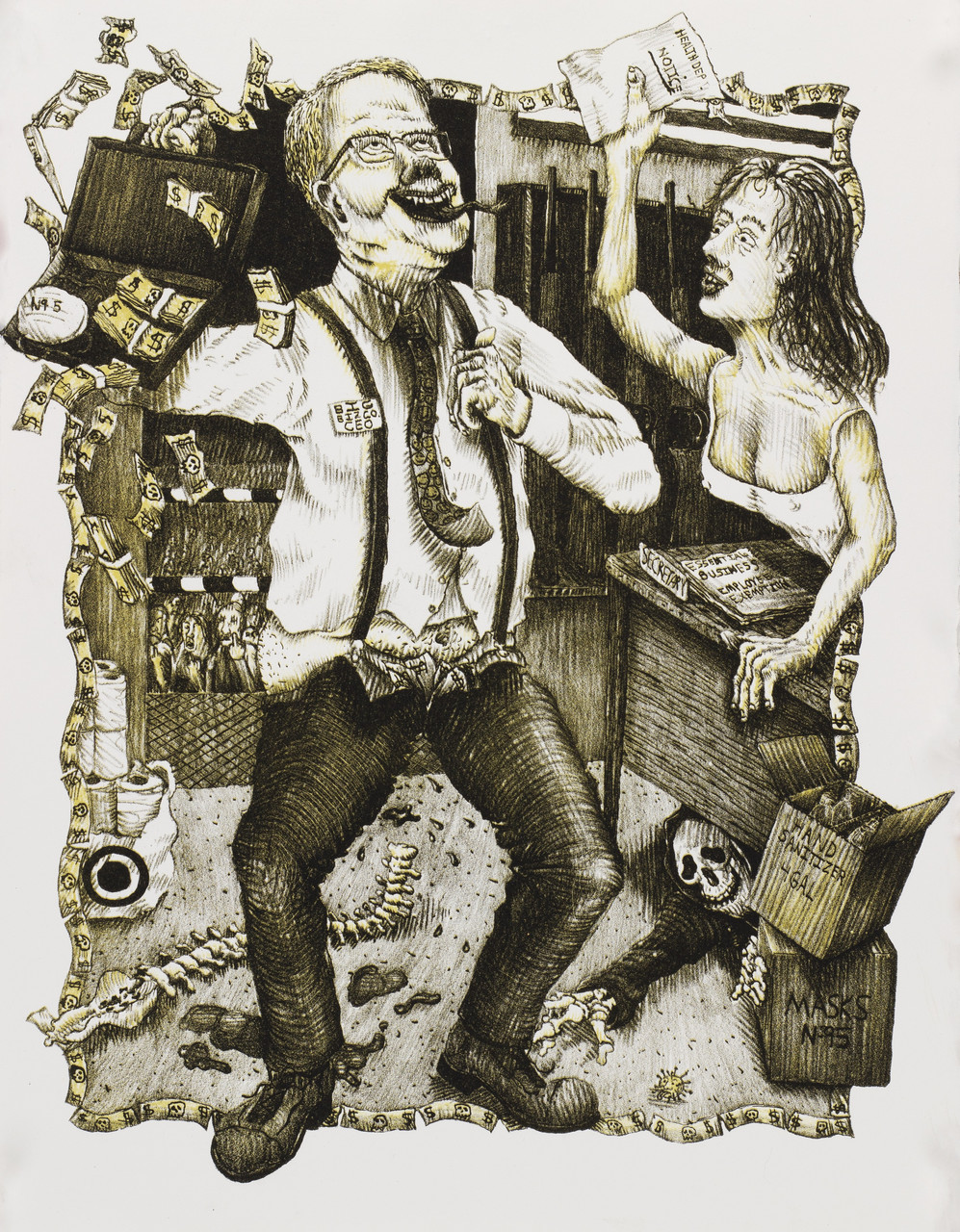

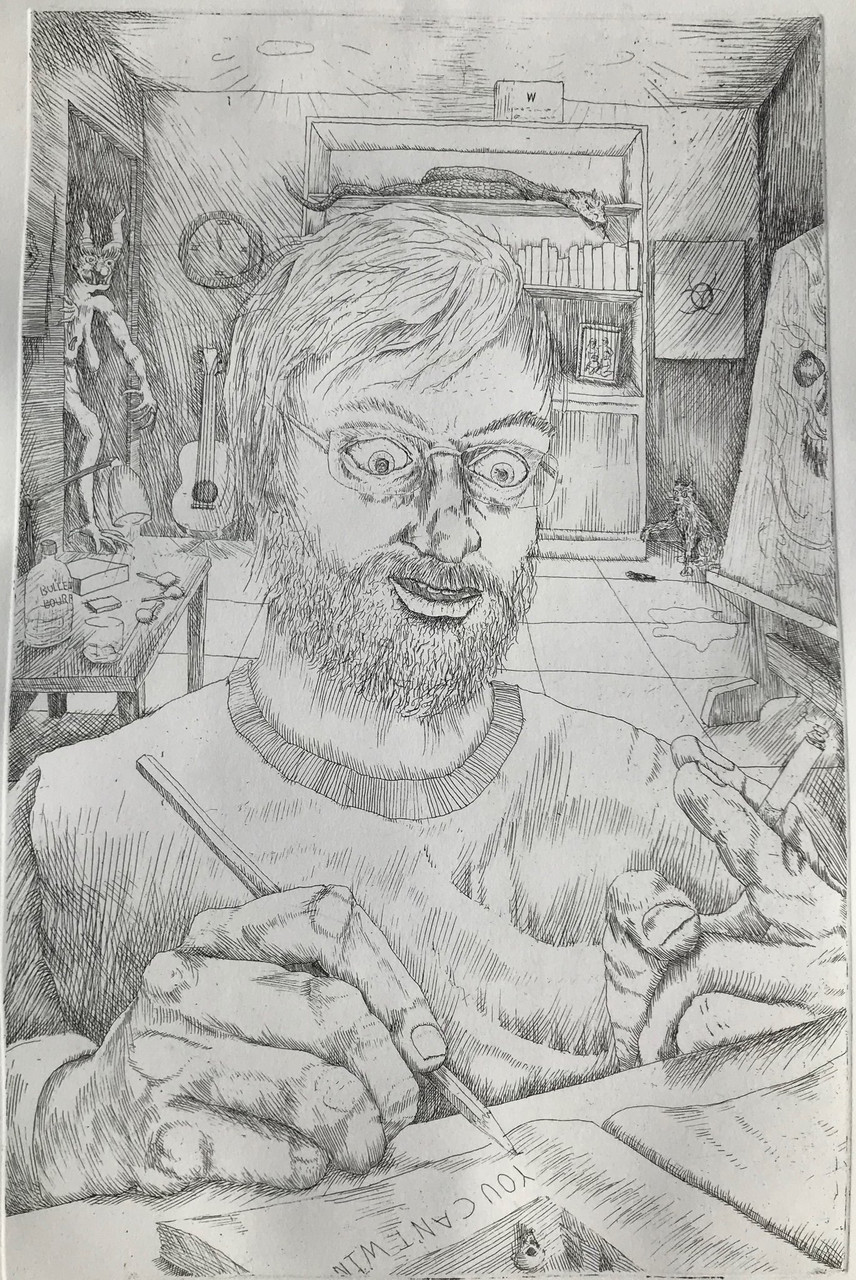

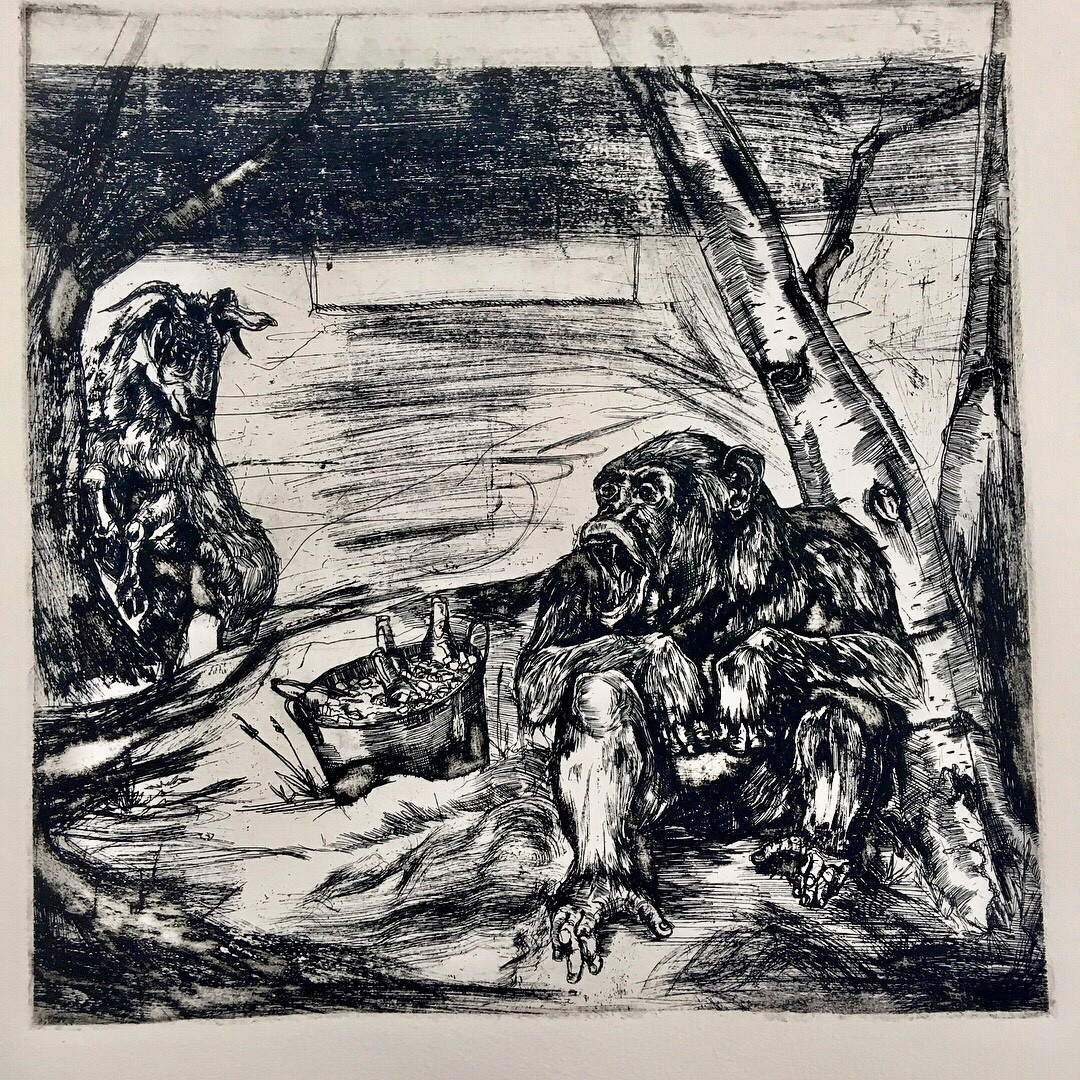

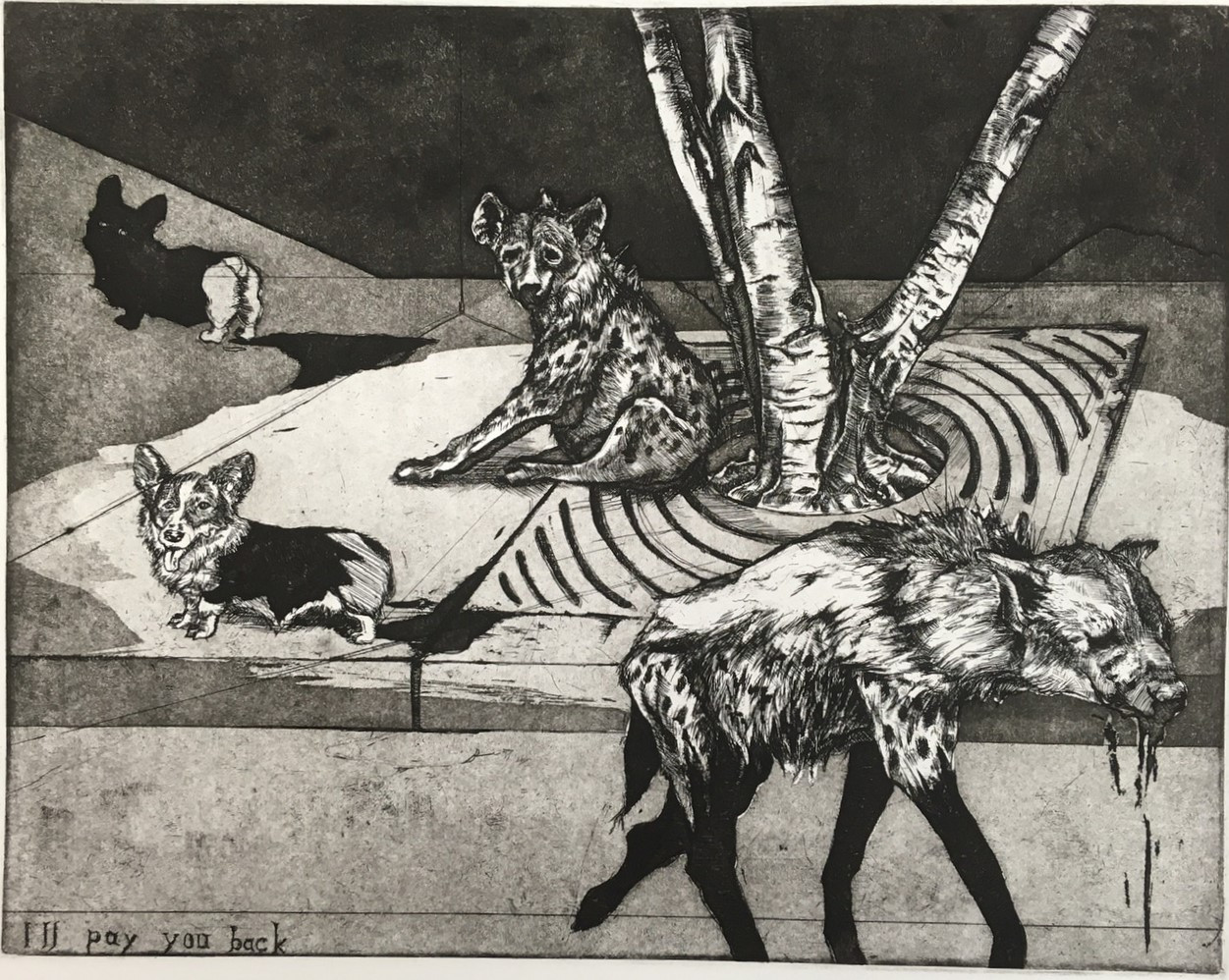

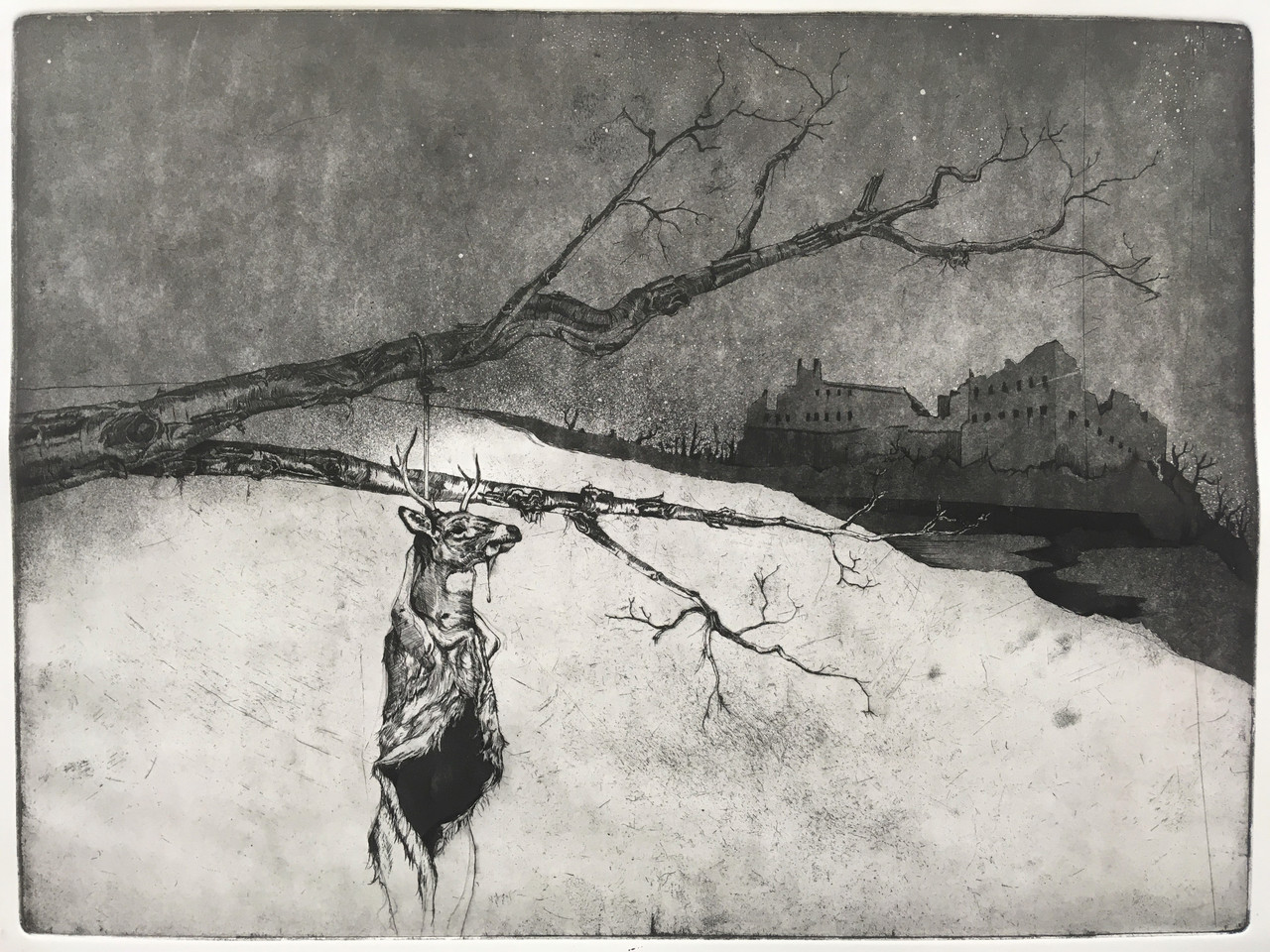

Ignorance is Bliss

I grew up in the American Midwest and was raised in Toledo, Ohio, an area commonly referred to as the “rust belt.” Located between the industrial U.S. cities Detroit and Cleveland that were affected greatly by economic downfalls like the 2008 recession and replacement of workers by technology. I saw firsthand the fall of industry and increasing job loss which had a devastating effect on my family. Witnessing the resulting years of abuse, addiction, and depression, I am interested in the state of working-class survival in American society in the face of class inequality. My artwork is a personal examination of experiences, hoping to bring attention to despair, tragedy and the need for change. Drawing from Nineteenth and Twentieth century printmakers like Goya, Daumier, and Posada who inspired action, I incorporate satire to provide some way to deal with the magnitude of the exaggerated reality we live in. My intention is to bring awareness through the lens of historical printmaking by generating powerful images that reflect the social condition of our time, while referencing the history of labor, American capitalism, and our environment. The unique technical challenges and materiality of printmaking is the connection to labor within my studio practice. I work in the traditional methods of woodcut and lithography to record and exploit the follies of our modern world. The historical role of print as a method of mass communication using the multiple is still effective in our technologically dominated world, through social media and the internet. My most recent woodcuts and lithographs have been made from a home studio after converting my garage to a functioning printshop amid the COVID-19 global health pandemic.

Max Hautala

Printmaking, MFA ’20

Live, Laugh, Love

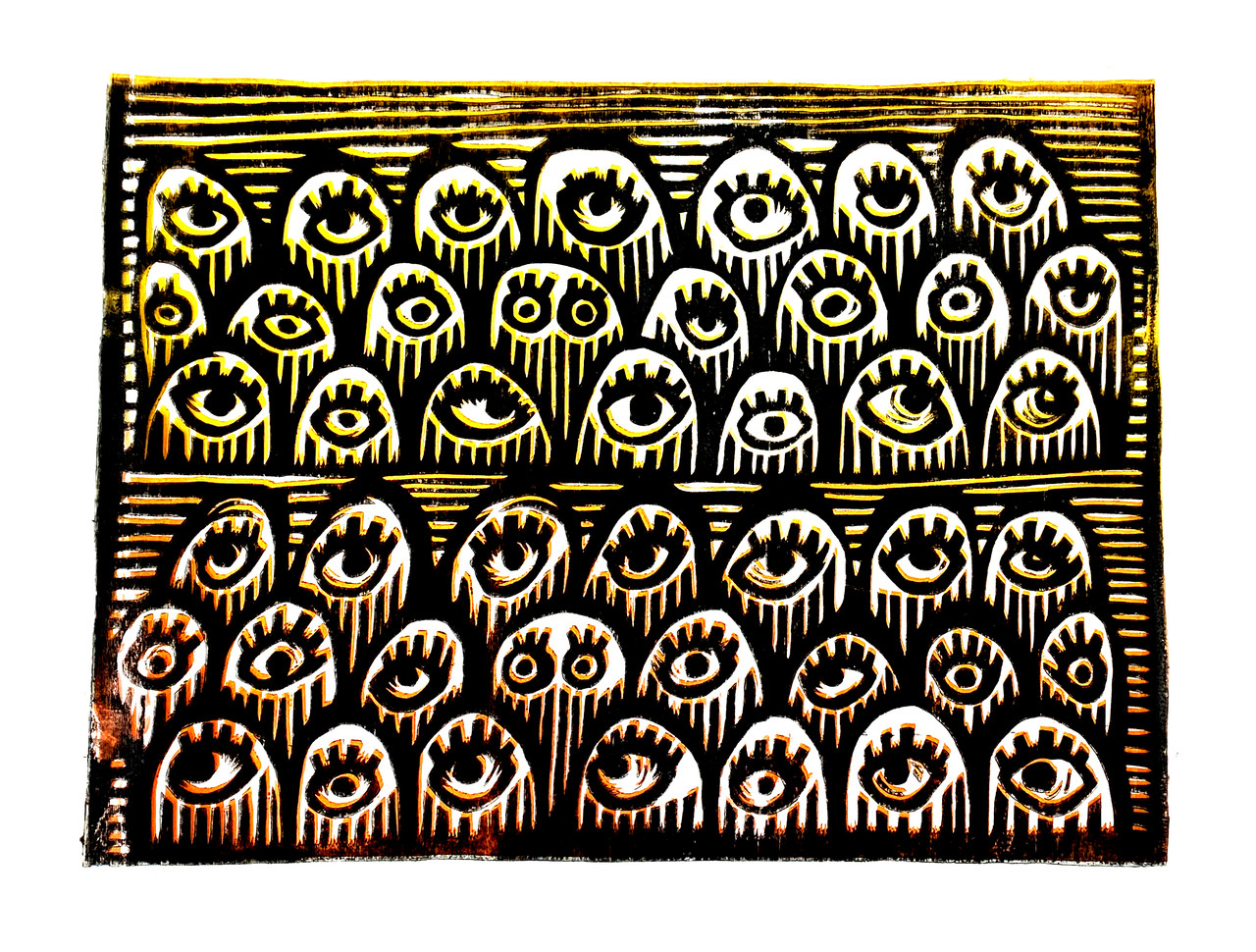

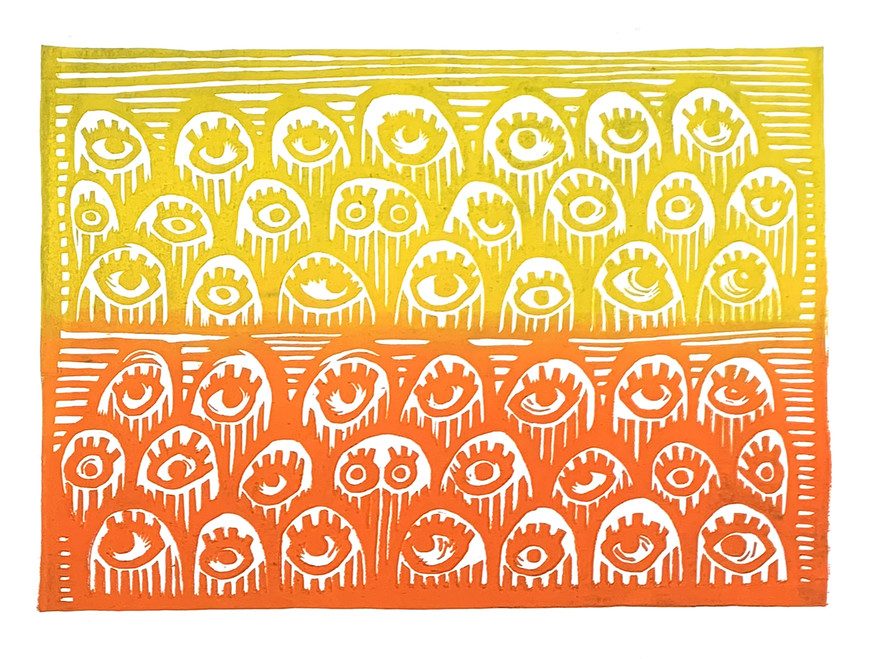

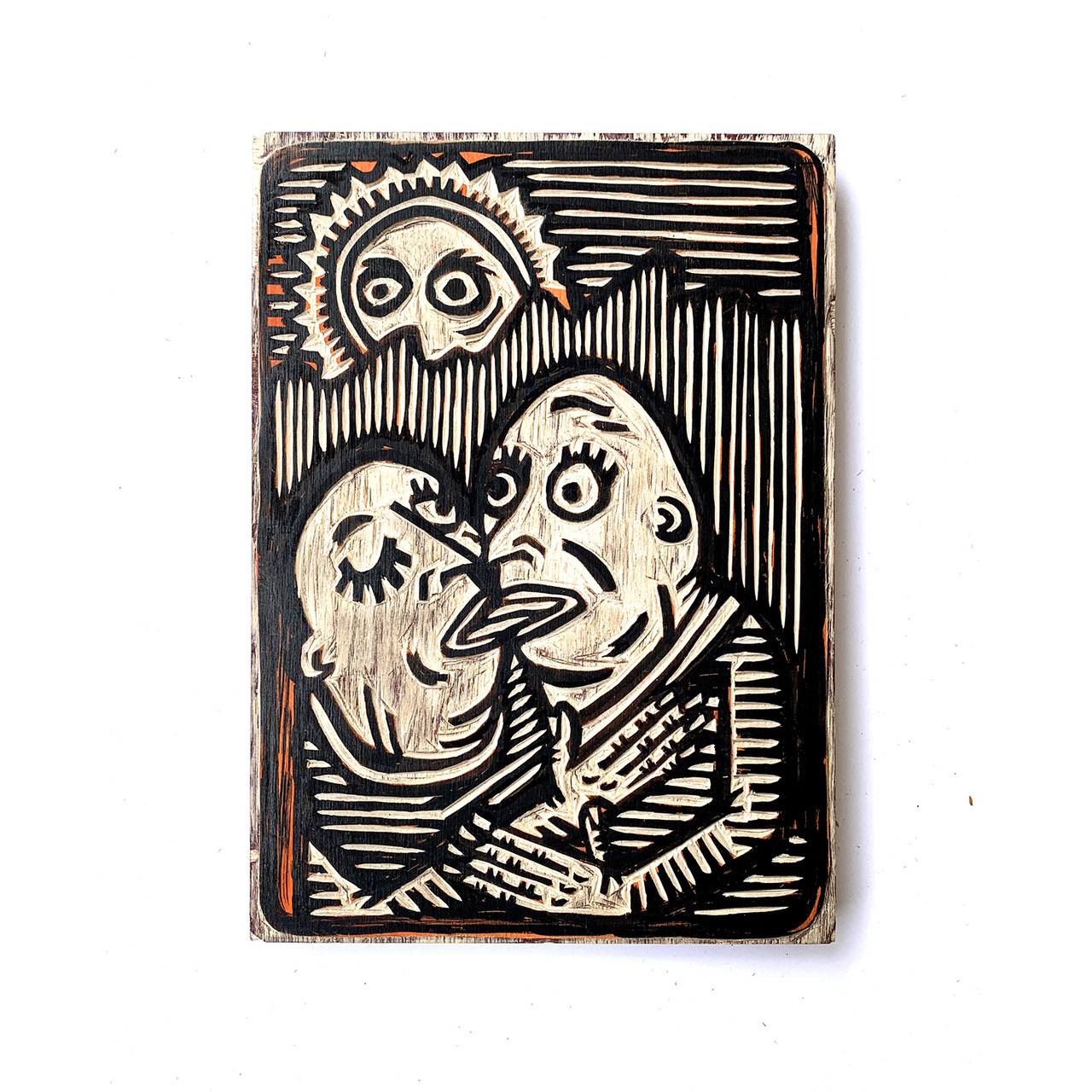

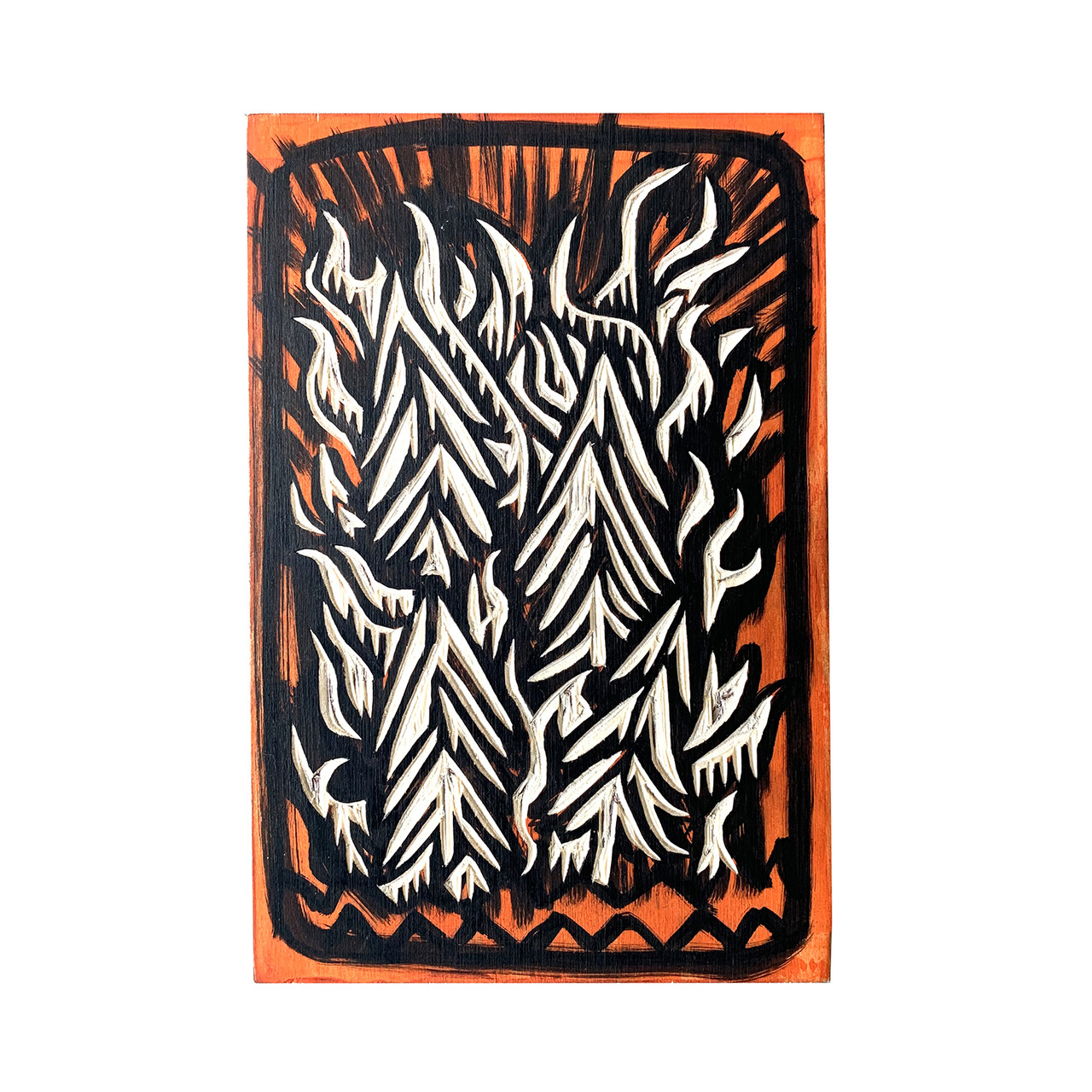

Live, Laugh, Love shows the world in a cheap mirror pulled from the trash. The viewer sees a reflection of their life warped by colors, forms, and ideas in a series of woodcut prints and blocks which fill the space. The woodcut process is the production of a reflection – much like the self-facing camera of a phone the produced image is a reverse of the original. This act of looking at distorted physical selfies of figures in the world creates drama between competing senses of normal. Allegorical in nature, these distorted figures stand in for the viewer. A viewer who exists in the age of the internet – an age where industry and nature are flattened. Active engagement with the physical world has become fractured as endless connections provide time for the transmission of ideas, viruses, exposure, and madness.

Mirrors, selfies, and internet culture are versions of reality. These prints and woodcuts do not wish to clarify but rather to question these realities. The familiar tiles fetishize the everyday closeness, interaction, and connection that is the human experience. Their proximity to each other in physical space and the hyper-stylized figures simulate something alien but knowable. The figures vomit, grope, kiss, consume, and ham for the viewer. The marks in the blocks reveal their emotional data—repetitive and cyclical like an internal dialogue—expressive and iconographic like the filters and emojis that litter our screens. Wallpaper-like prints cover the majority of the space. Despicable Me 5 sets a structural tone with playful colors and uncounted eyes looking back at the viewer. The walls, like the screen world, offer no visual resting place.

I find joy in the physical process of making woodcut prints. Yet I also find irony in my consumption of materials – wood, ink, paper – as I comment on consumerism. Humans mediate their participation in life through technology. We also use technology to understand life. In Live, Laugh, Love I use the technology of yesterday to understand the influence the technology of today has on my life and to try to answer the question: am I really going anywhere if I’m looking at my screen all of the time?

Kel Mur

4D, MFA ’20

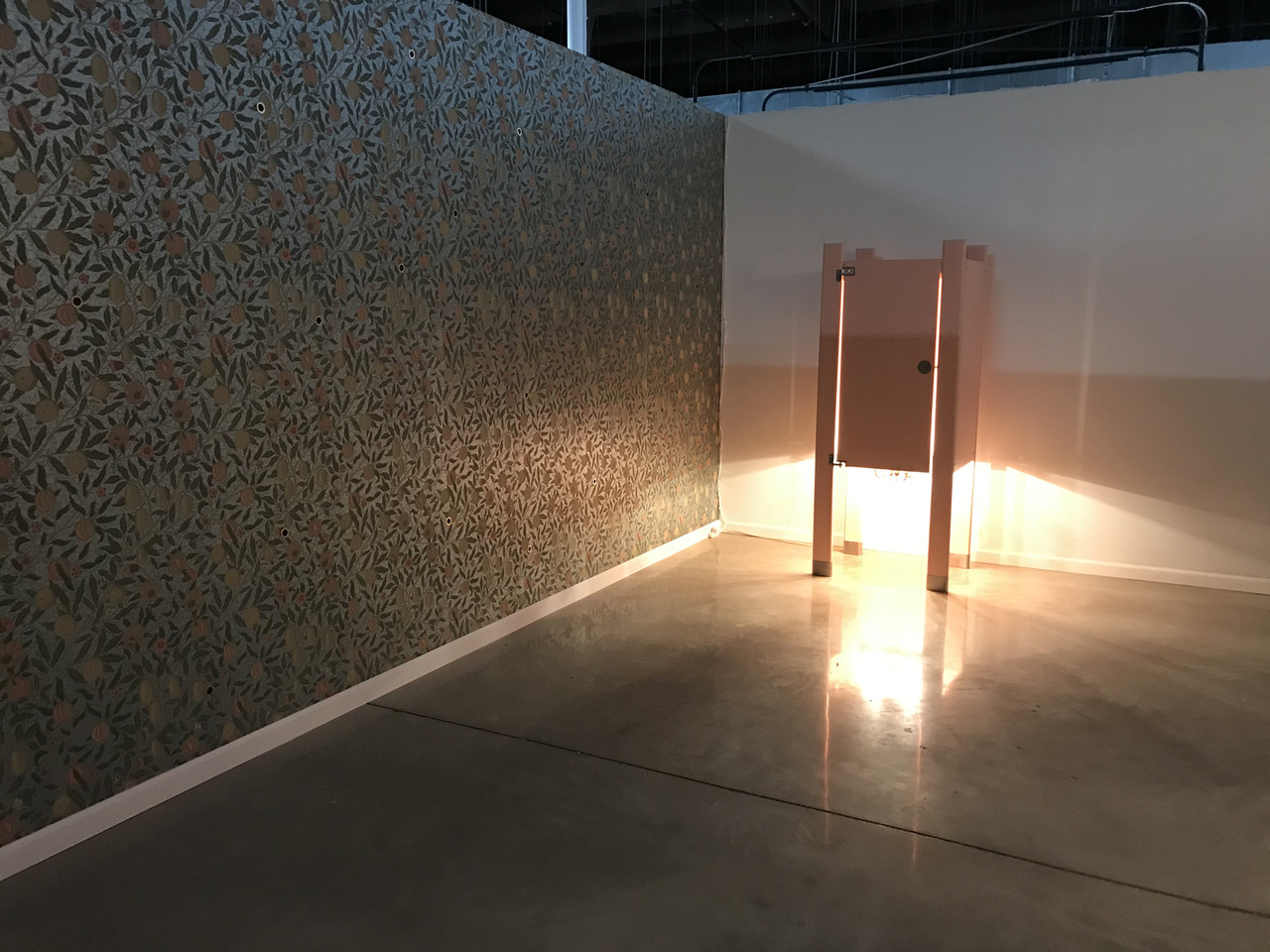

Heirloom

I am detached, estranged even, from where I come from, yet I carry many of the same burdens that my ancestors did. This weight lives in my body dictating how I accesses memories and how I process the present moment. The lens through which I look at the world is colored by those around me who have helped shape it—some did a better job than others.

The relationships I’ve had or haven’t had with my family in their periods of ebb and flow have seeped into how I search for romantic partners and how I recoil from being parented. The tension between my desire for independence and yearning for someone to deeply care for me often manifest with a chasm between them, and these innate parts of me seem to be in need of reconciliation. As I search, this dissonance in me teeter-totters in unbalance. Sorting through these emotional artifacts brings to light heirlooms that I do not have to accept, things that I do not necessarily have to pass on. However, this does not mean that the life they have created is easily resolved, that the passing of time is not continuously marked by their residue in ways that I am always rediscovering.

Cate Richards

Art Metals, MFA ’20

Turnips, Like Skulls, Are Heaped House High

There is a fascination with the past. As we delve further into a digital age, analog tools of the hand – tools which require movement and feeling – span further away in the timeline with each passing year. With that, our interest in them grows. They become mythological fetish objects of our romantic notions and false memories of history.

I too find magic in the old. Pre-industrial tools and their relation to creation and craft, their forms, textures, and sounds are the ingredients for my own personal ritual objects. These rituals are my own and no one else’s.

This is a false anthropological display, the subject of which is myself and my ceremonial rites and tools. They are indulgent, a pastoral gothic, somewhere between jewelry and tool. They attract and repel, stimulating a simultaneous curiosity of the past along with repulsion and confusion.

Taylor Kurrle

Glass, MFA ’20

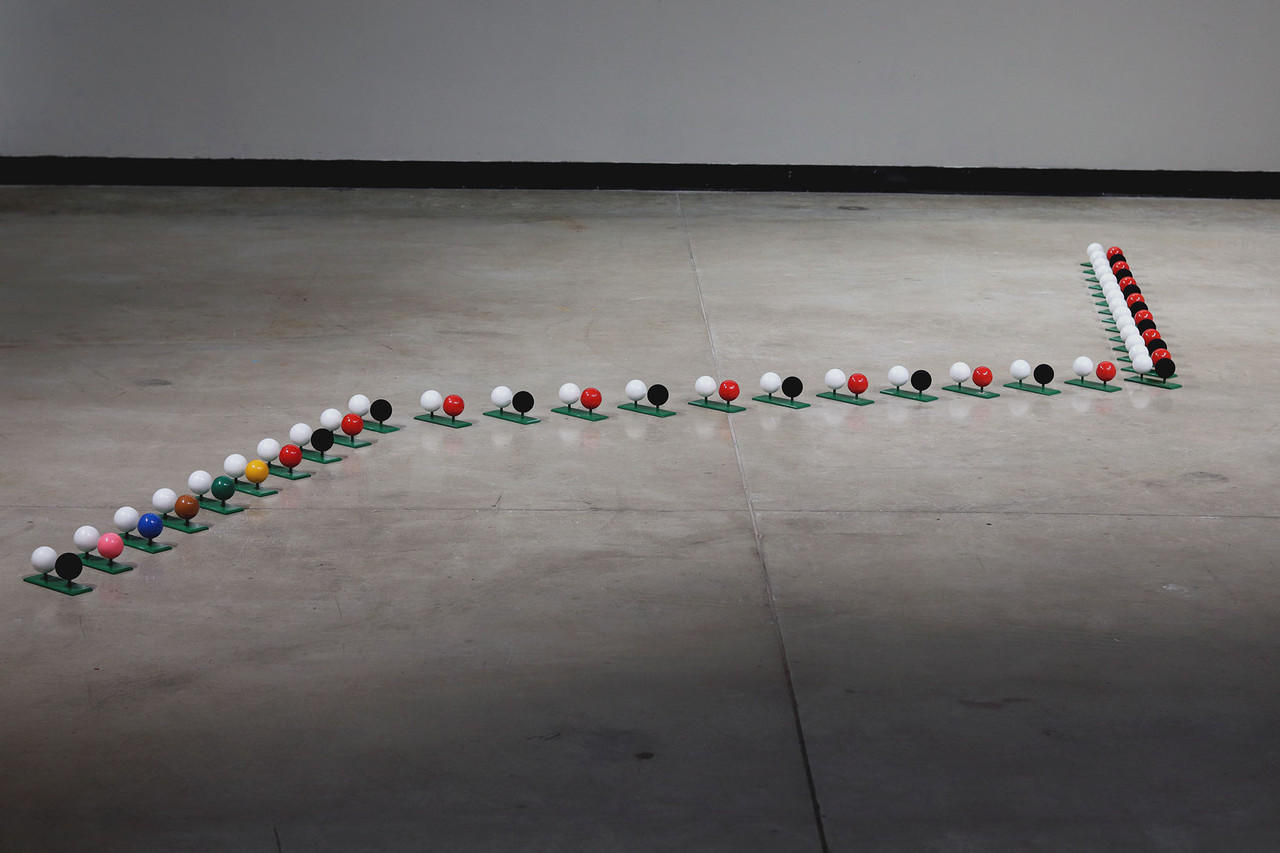

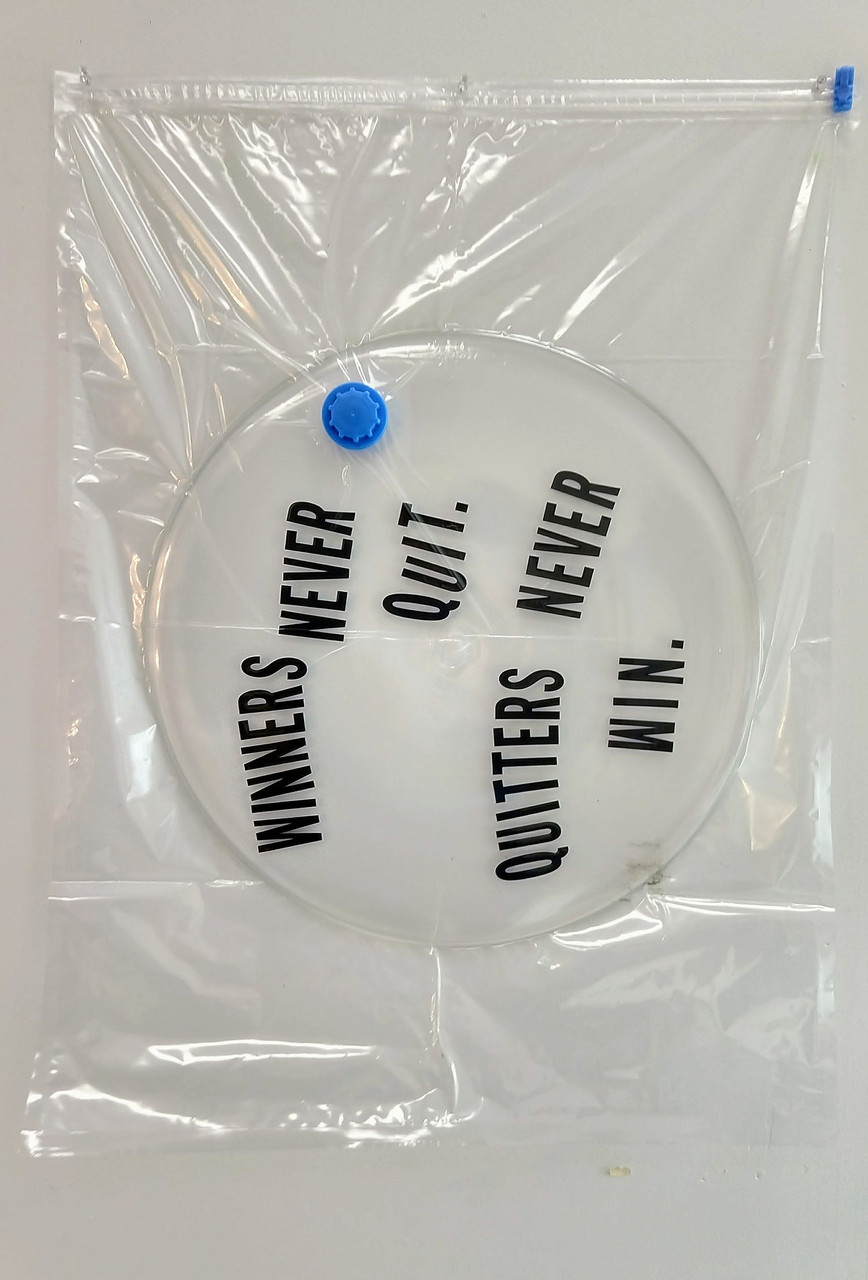

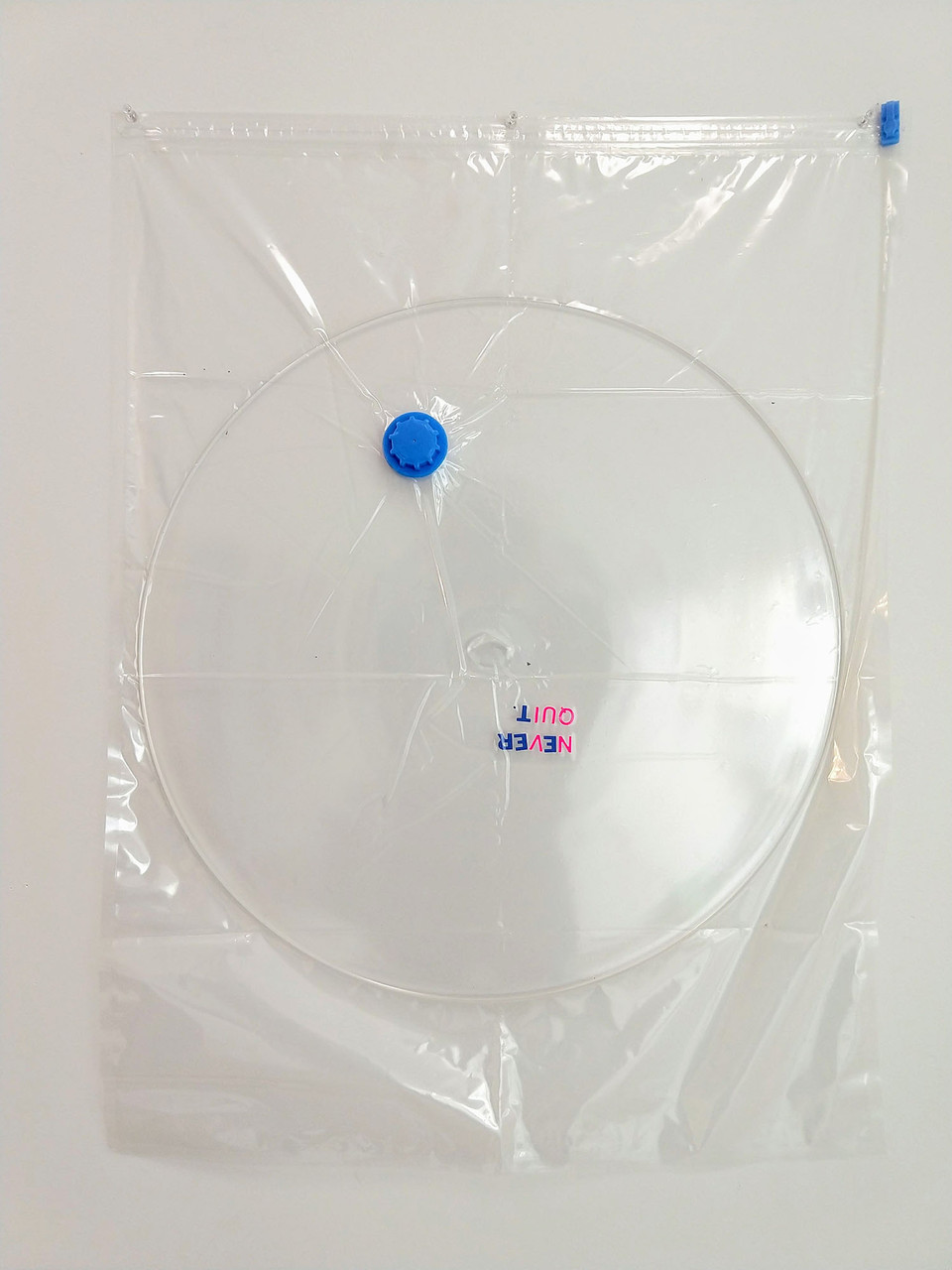

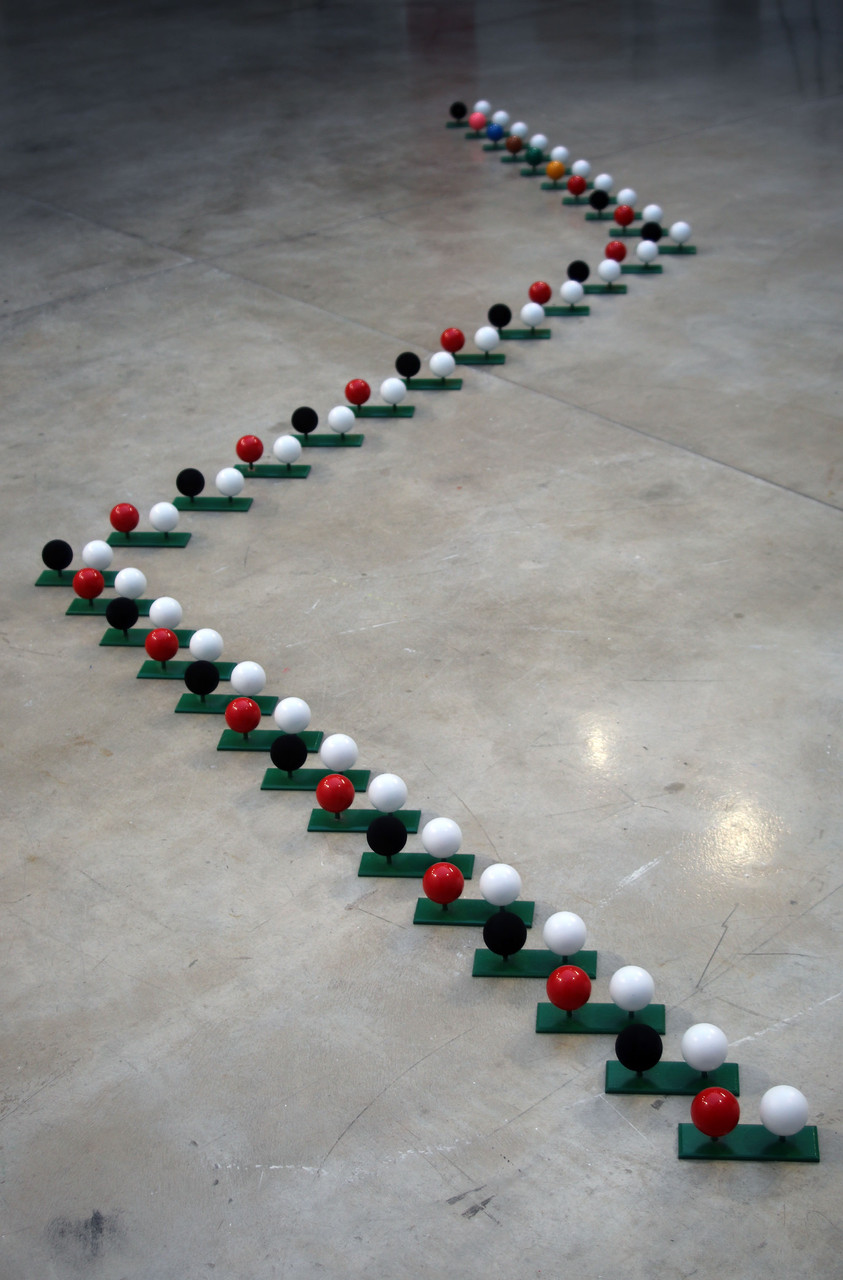

Not Sport

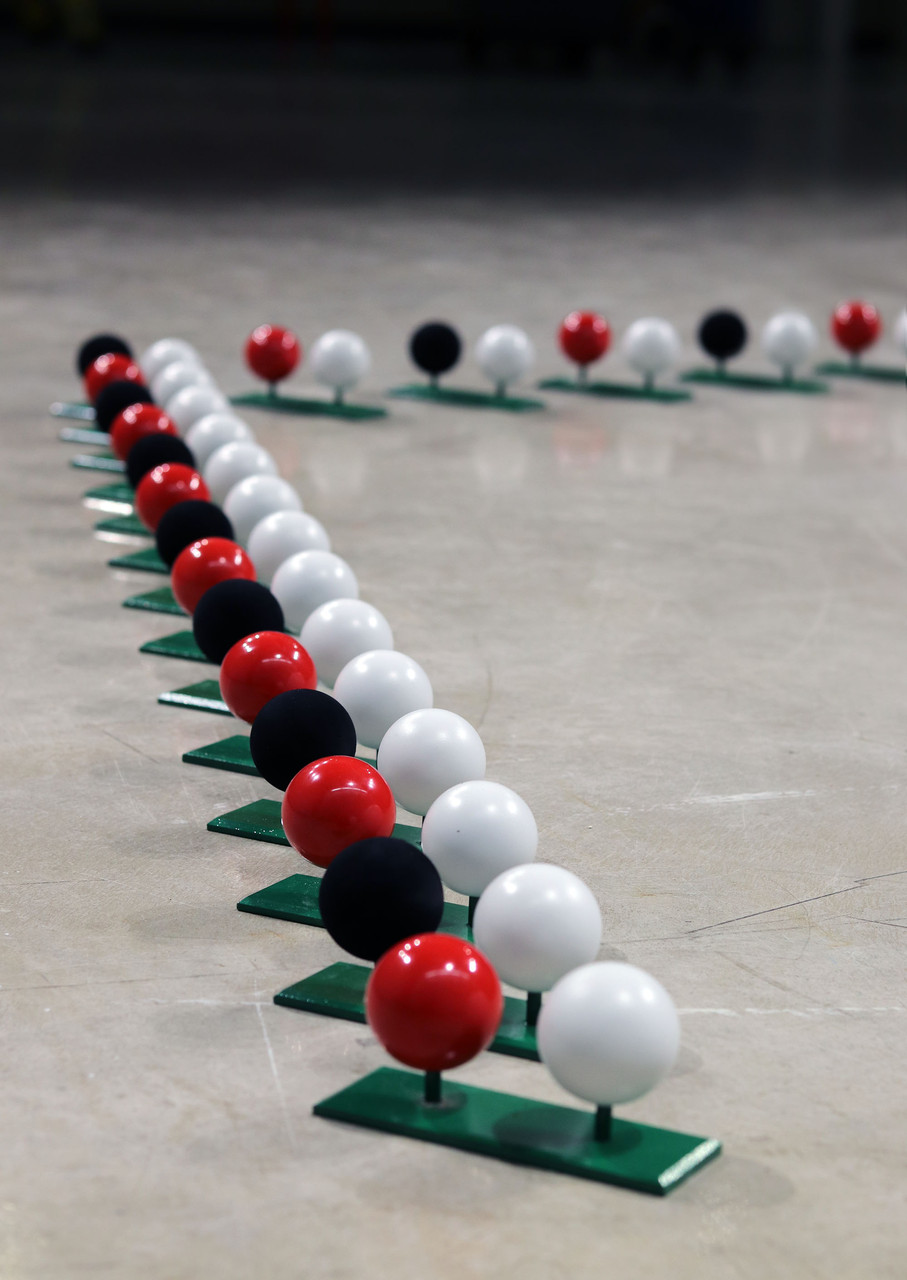

Sport, but not a sport – the overarching community and power that sports assert over society through sports conduct, morals, and ideologies. This body of work is a story materialized through the iconography of sports and our human relationship, individual and communal, to sports and its social market of interaction.

A moment of the story is fractured, flattened, and framed. The timeline of the story revealed through material use and historical references where ideas are undone, exposed, and made vulnerable. Our human experience is constructed around sports through work and reward, order and discipline, community and team—communal concepts communicated through the conduit of objects that mark the participant with physical memory.

Noël Ash

Painting & Drawing, MFA ’20

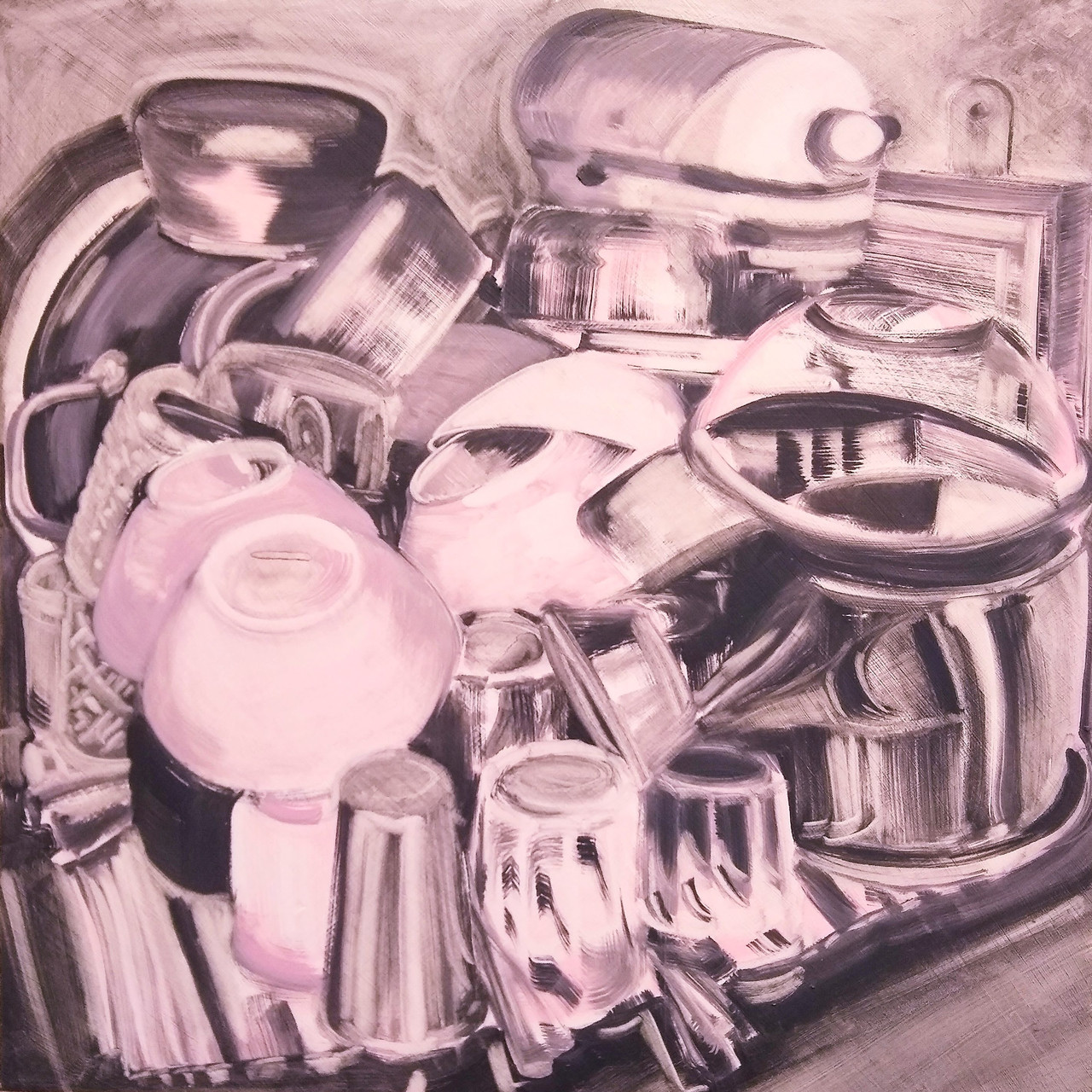

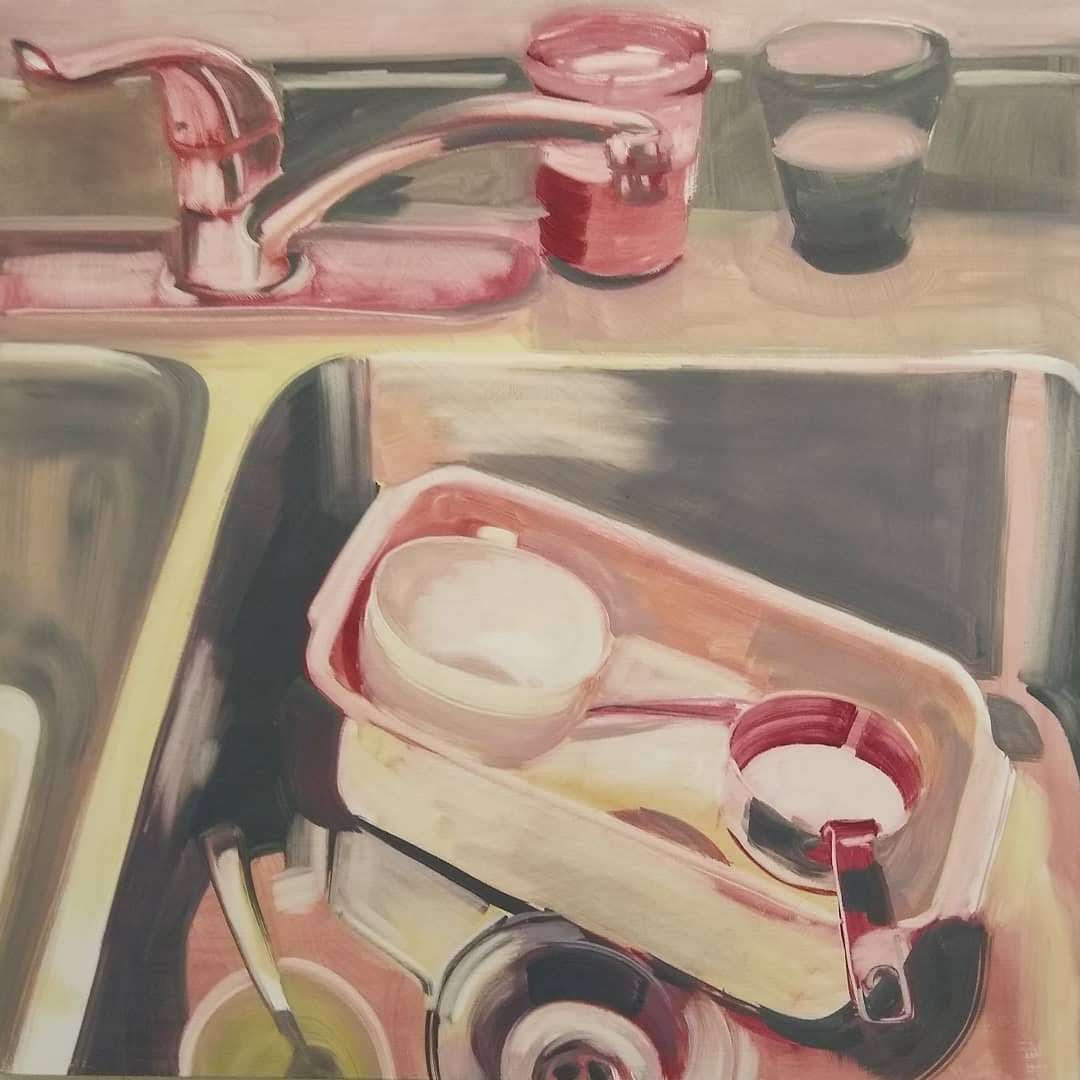

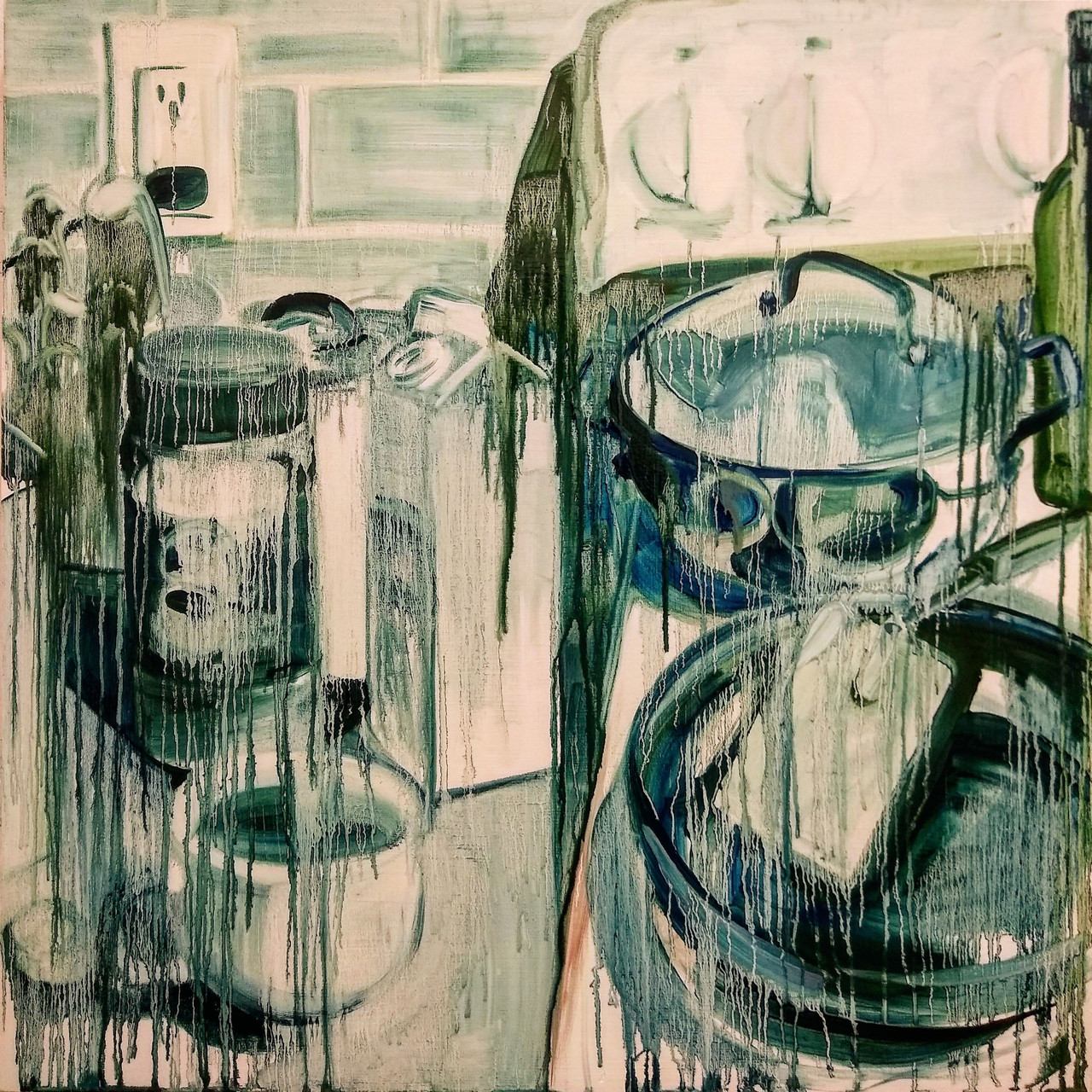

Things Pile Up

The kitchen has long been gendered feminine, and I use it now to explicate my position in motherhood. Mothers of every generation have found in these confines the generator of creative output. There is a freedom there – the freedom to create and destroy. There is drudgery – the repeated banality of rot and scum, of others’ spit and scrapings. There is also achievement: The seven-course dinner, the birthday cake whisked out at the last moment; the tower of sparkling dishes left to dry; shining sink, bare counter.

Dishes humanize the task of mother. Very few of us do not grapple with these objects in some way. All but the hideously spoilt have a relationship with the kitchen. Mine is mostly positive. It is the kingdom where I reign. Yet, at times, it seems to rule me. I get behind, or maybe my family gets ahead. Things pile up.

In settling my eye on the banality of the kitchen, I consciously elevate it to the level of consideration that oil painting has historically insisted upon. I like to think that I am revealing the beauty that resides, mostly unseen, within the mundane, even when it threatens to overwhelm.

This work comes on the heels of my last two exhibitions, in which I examined the daily conflicts of motherhood: WHY MOM and Aquaphobic. My work has, for the last few years, striven to examine and memorialize the frustration and humanity of motherhood, and to make a monument out of daily drudgery.

As an ArtMom (patent pending) I cannot help but examine the plight of my daily existence. This is my territory. These quiet monuments are both still life and landscape. Hence, the square.

Noël Ash is one of two 2020 Arts + Literature Laboratory Prize winners. A local Madison community-driven contemporary non-profit arts organization, the ALL provides the visual, literary, music and performing arts that presents over 200 events per year, mostly free or low-cost, and year-round arts education for all ages, working to make the arts more accessible and sustainable in our community.

The annual ALL Prize exhibition award is given to one or more graduating MFA candidates from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, selected by members of the ALL curatorial board. The prizewinner’s MFA thesis exhibition is shown at ALL, and the prizewinner receives a $1,000 stipend to assist with exhibition expenses and installation provided by the Art Department. Winners Noël Ash and Emma Pryde‘s shows at the new ALL Livingston Street location have been postponed.

Kitchen Rythem by Noël Ash

This is the time I have taken

totting up tallies

Think on the seasoned pan,

Simmer the stove, seven to seven-fifty.

Whippy spatula, flip. flip.

Dim

the bubbled scum.

still I sink, sudsing internal.

stacked stoneware precipices

always anticipating

silence.

This is the territory I inhabit.

water cups,

last night’s coffee,

So.

drips slide

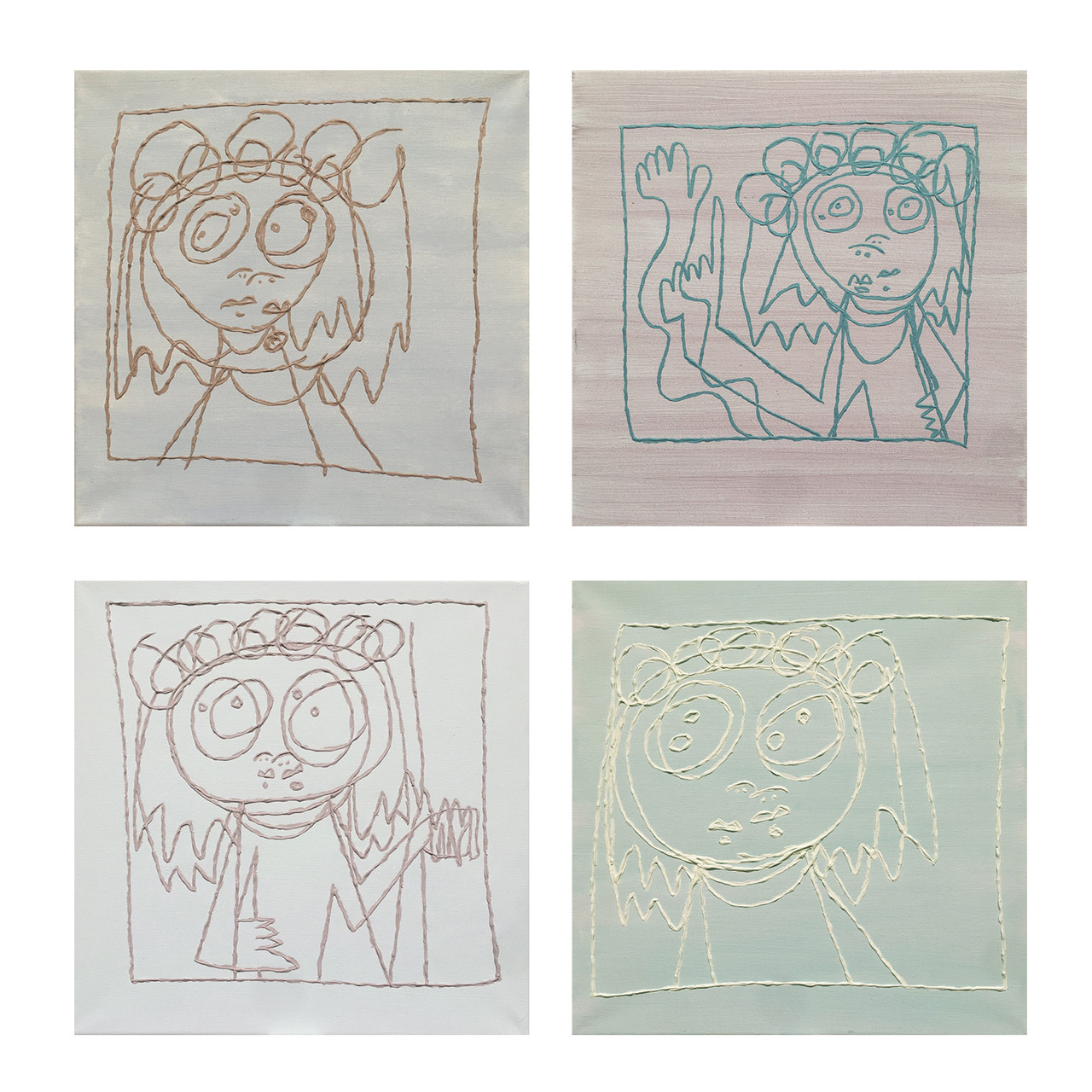

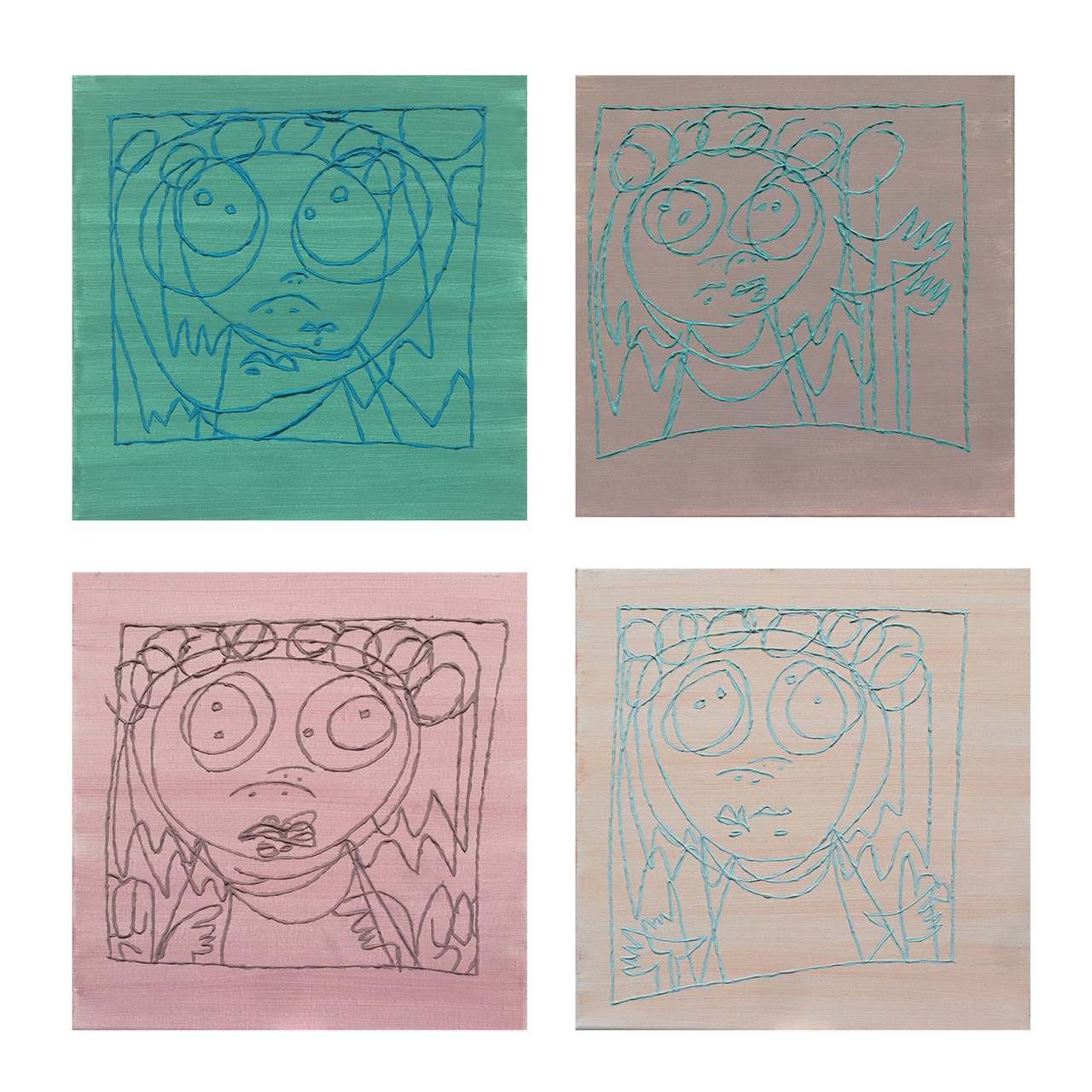

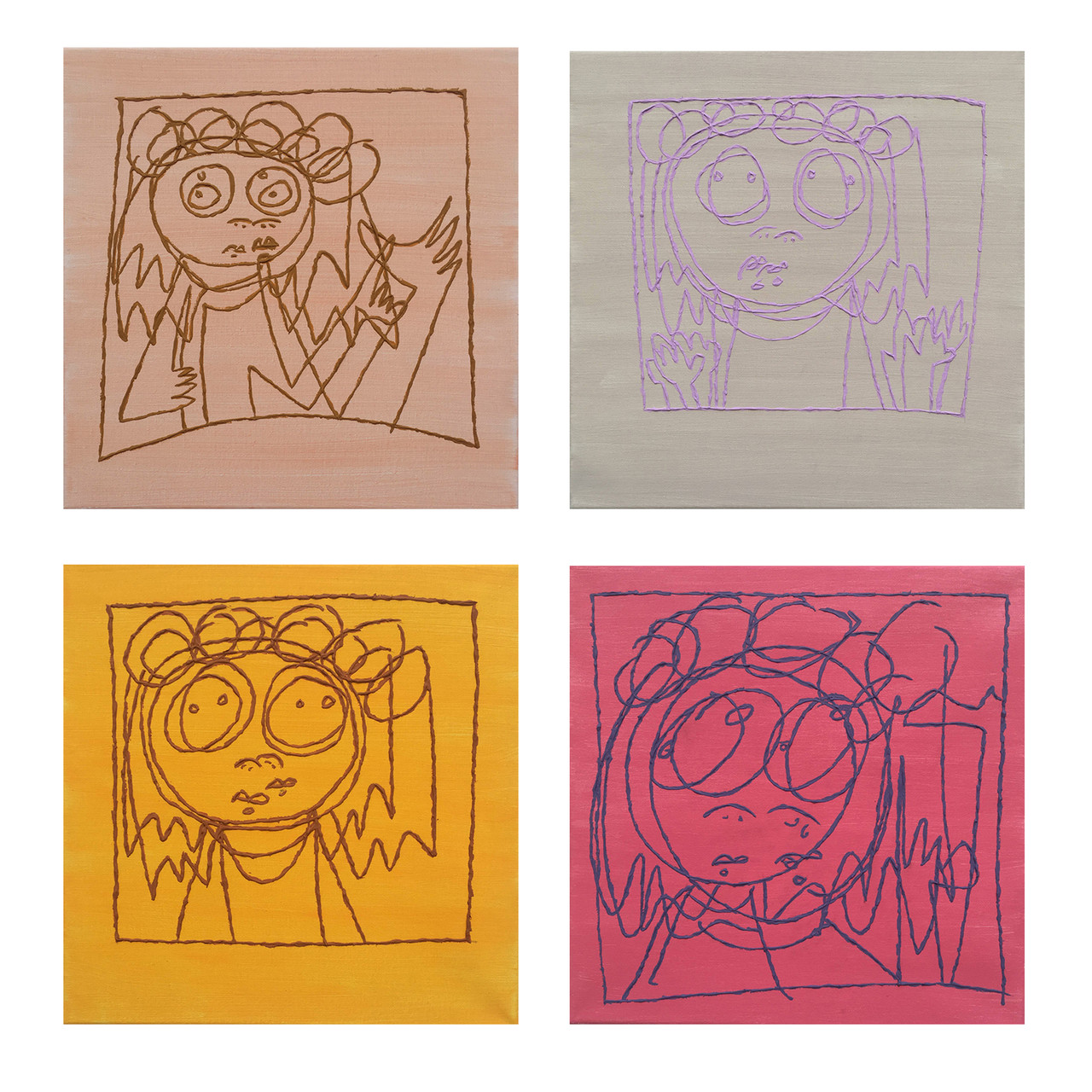

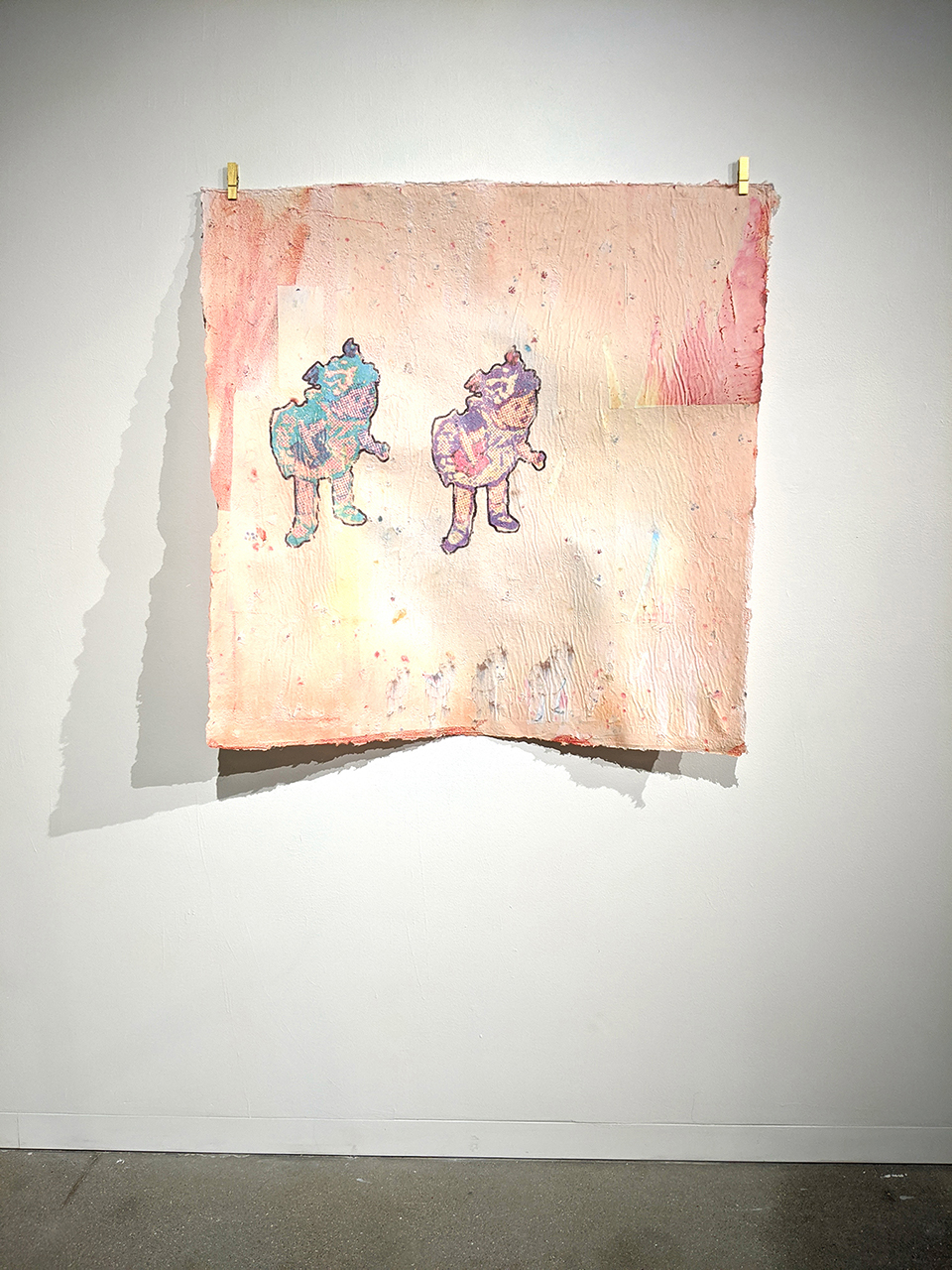

Deanna Antony

Painting & Drawing, MFA ’20

How To Cover Your Dark Eye Circles

I had been trying to make the best out of a tragic situation for the last year. The work for my canceled MFA Exhibition How To Cover Your Dark Eye Circles was a collection of paintings made during that cycle of grief. My personal practice took comic form to help me cope with loss, and offered me a way express the things I needed to, without feeling like I would bring someone down. I devised a method of translating this comic form into painting, and they became a meditation on color, line, and acceptance. Before this process was interrupted by COVID-19, I managed to make 57 paintings. Some of these paintings have entered a new phase since relocating studios.

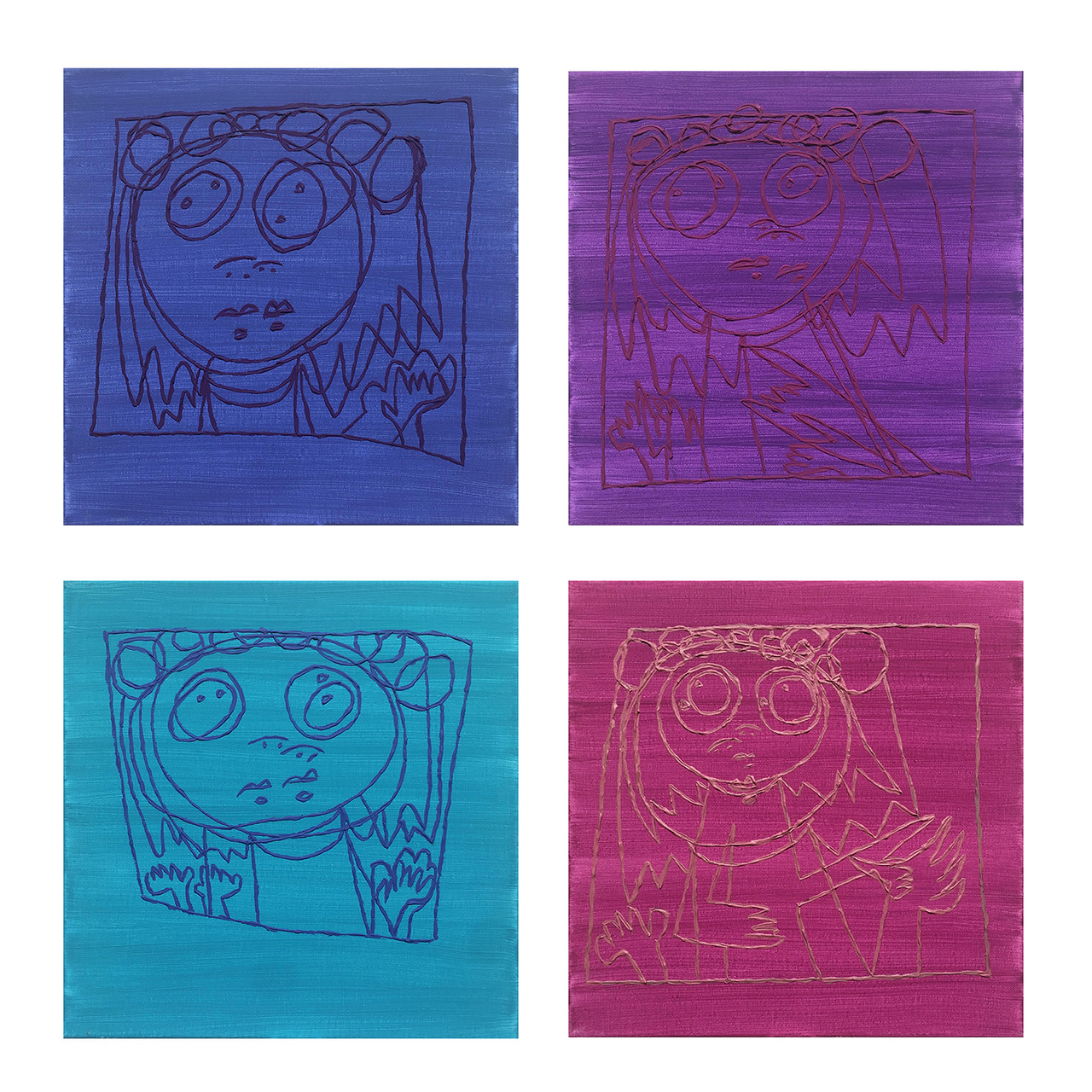

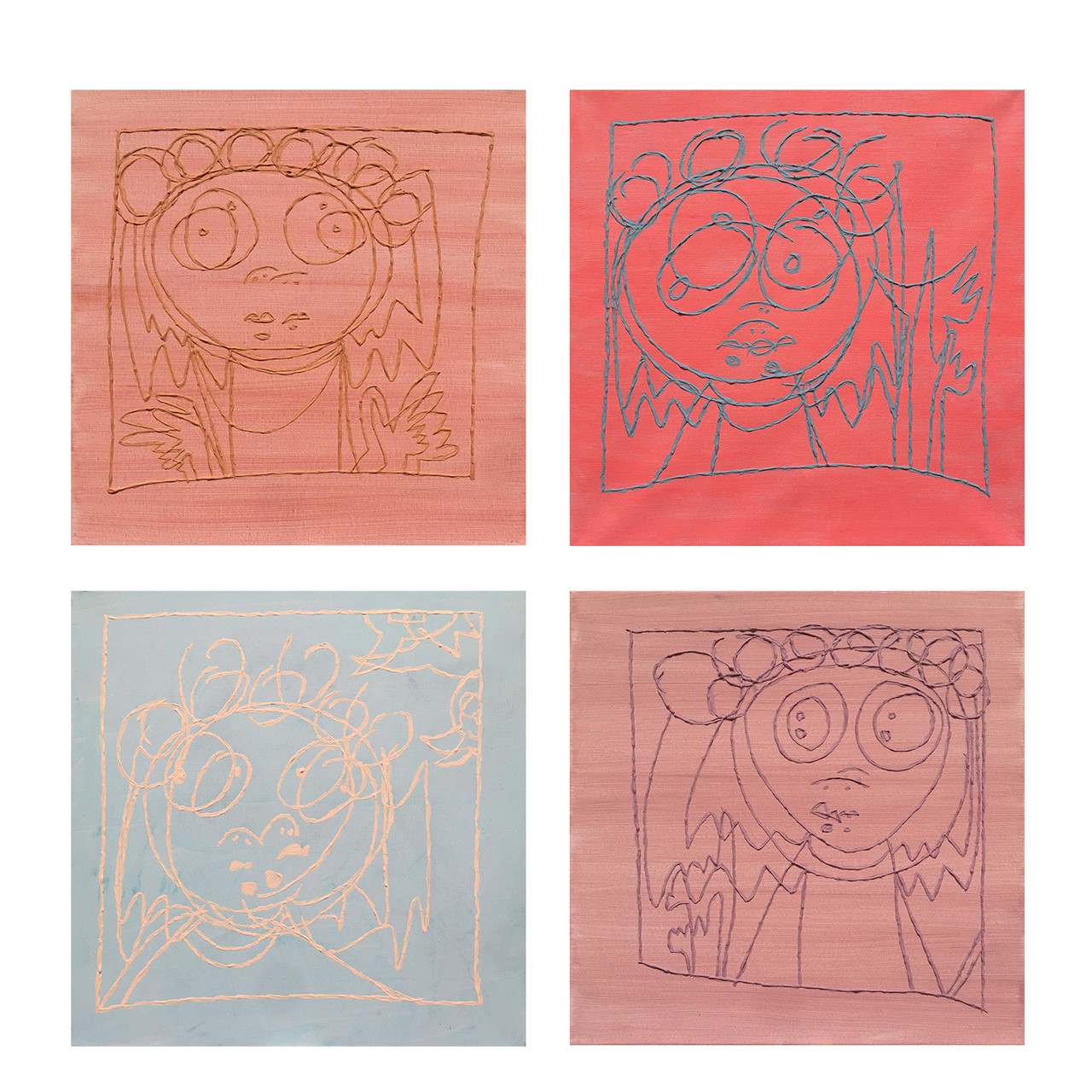

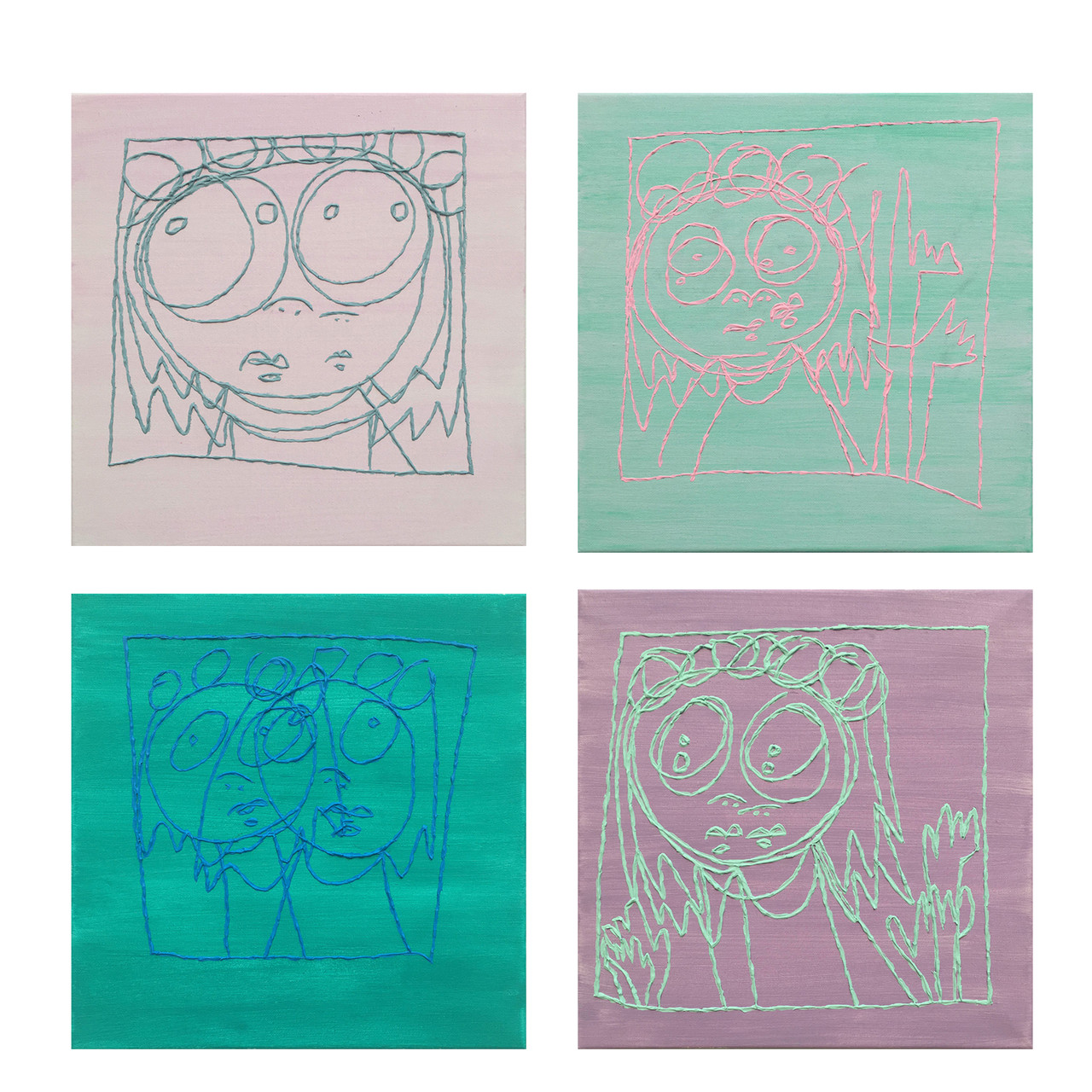

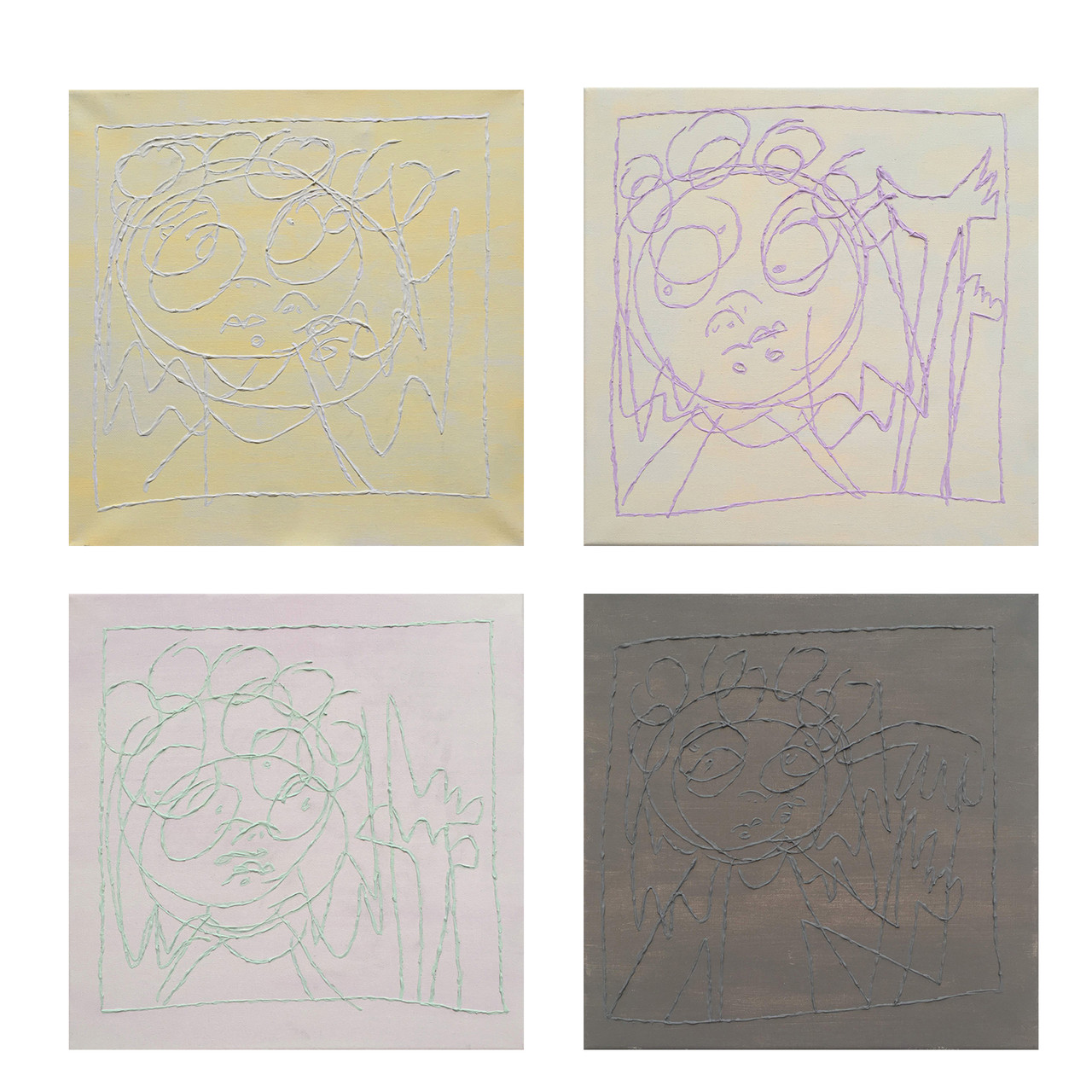

Each painting starts with a swiftly drawn lyrical square frame, containing a dizzy line drawing depicting a double vision image of my self-portrait comic character experiencing an in-between moment. The lines are meticulously painted on with a thin brush and a dip, drag, twist paint application I developed in order to mimic puff paint, embroidery, and paint applied directly out of the tube. After the goopy twist line is applied, the same color is used to immediately to apply the horizontal wash onto the ground of the next painting.

The color interactions are reflections of combinations of toy and TV chroma found in my childhood in the late-80s to the mid-90s; Popples, Carebears, My Little Ponies, Huggabunch, Gummie Bears, Pee-Wee’s Playhouse, Eureeka’s Castle, to name a few. The paintings are displayed in groupings and faux-installations. If my physical show was to be canceled, then I would take my own liberties with the presentation of the work. The quarantine lent itself to unexpected opportunities to explore absurd and personal sites.

Some unimaginable things rip apart your soul and need lots of time to heal from, and some unimaginable things are the greatest gift and bring immense joy and satisfaction.

Autumn Brown

Illustration/Graphic Design, MFA ’20

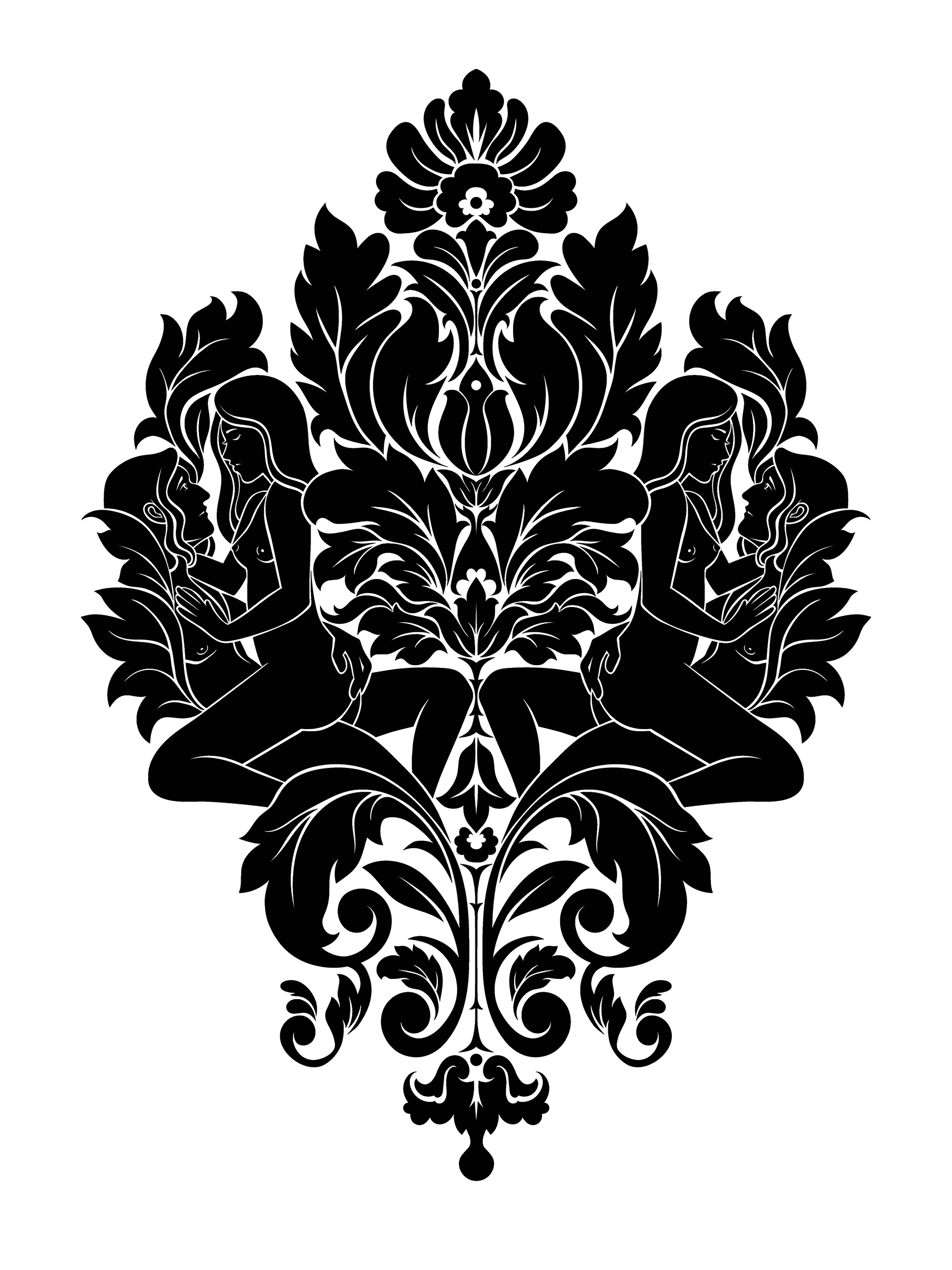

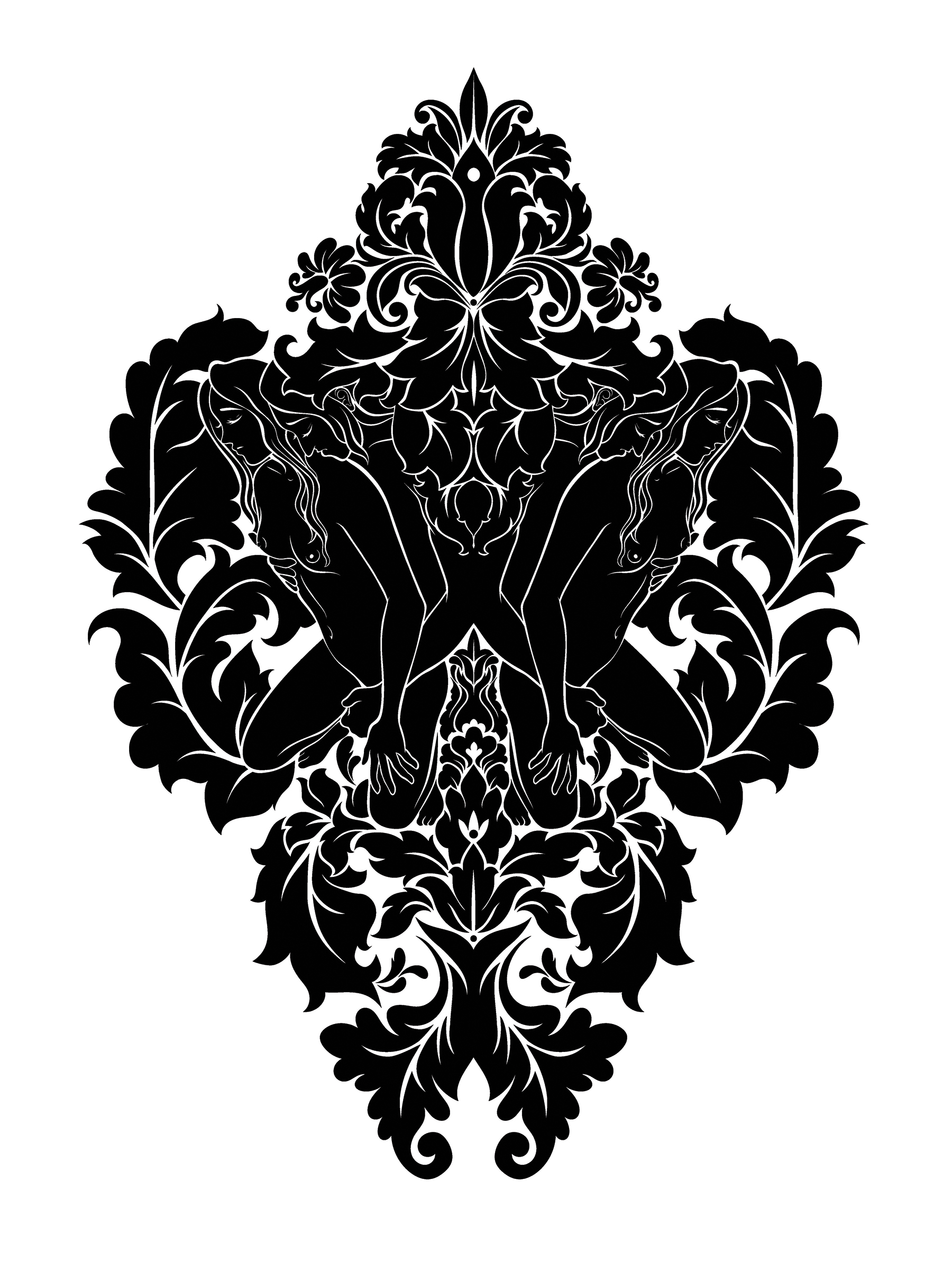

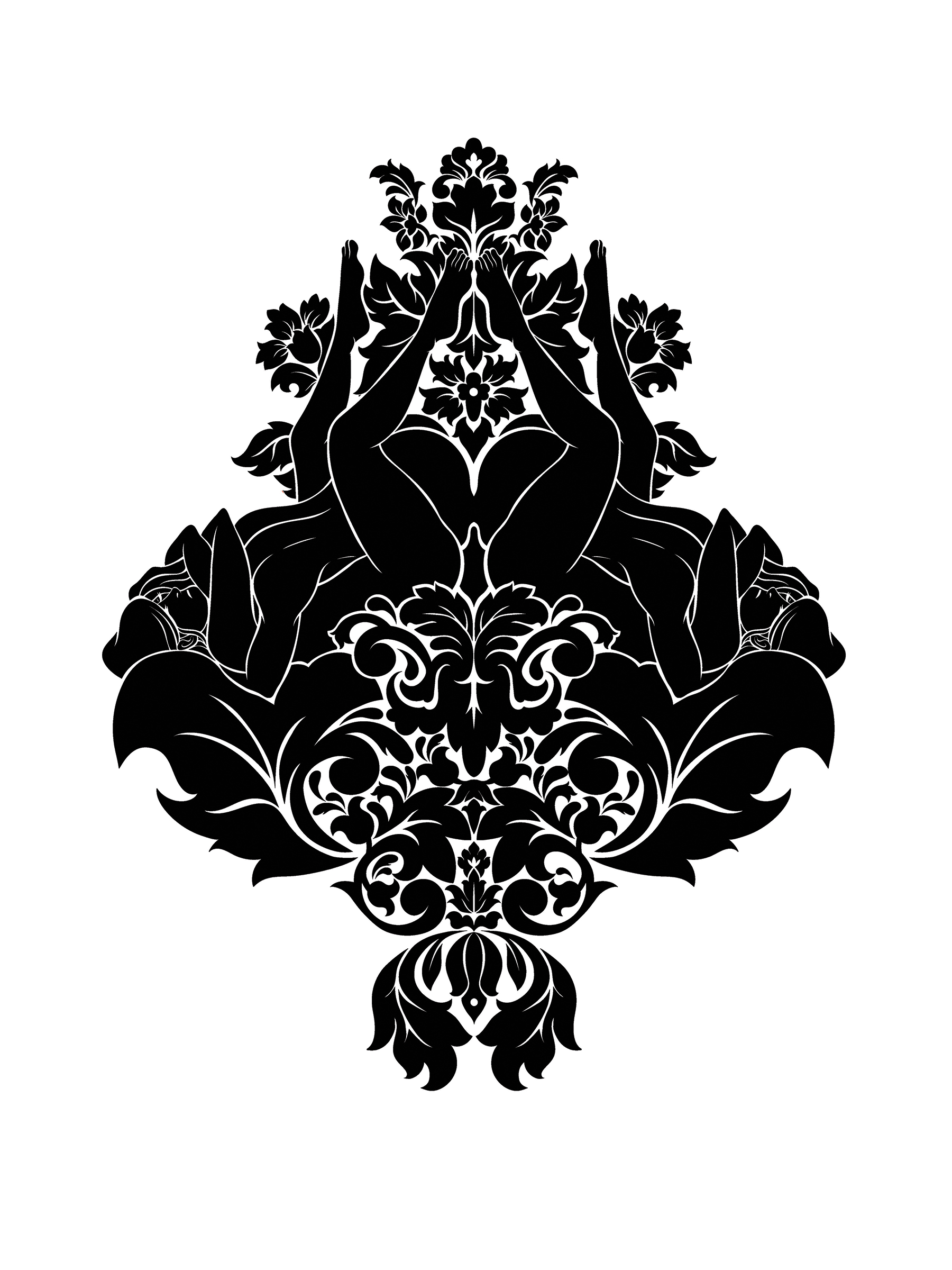

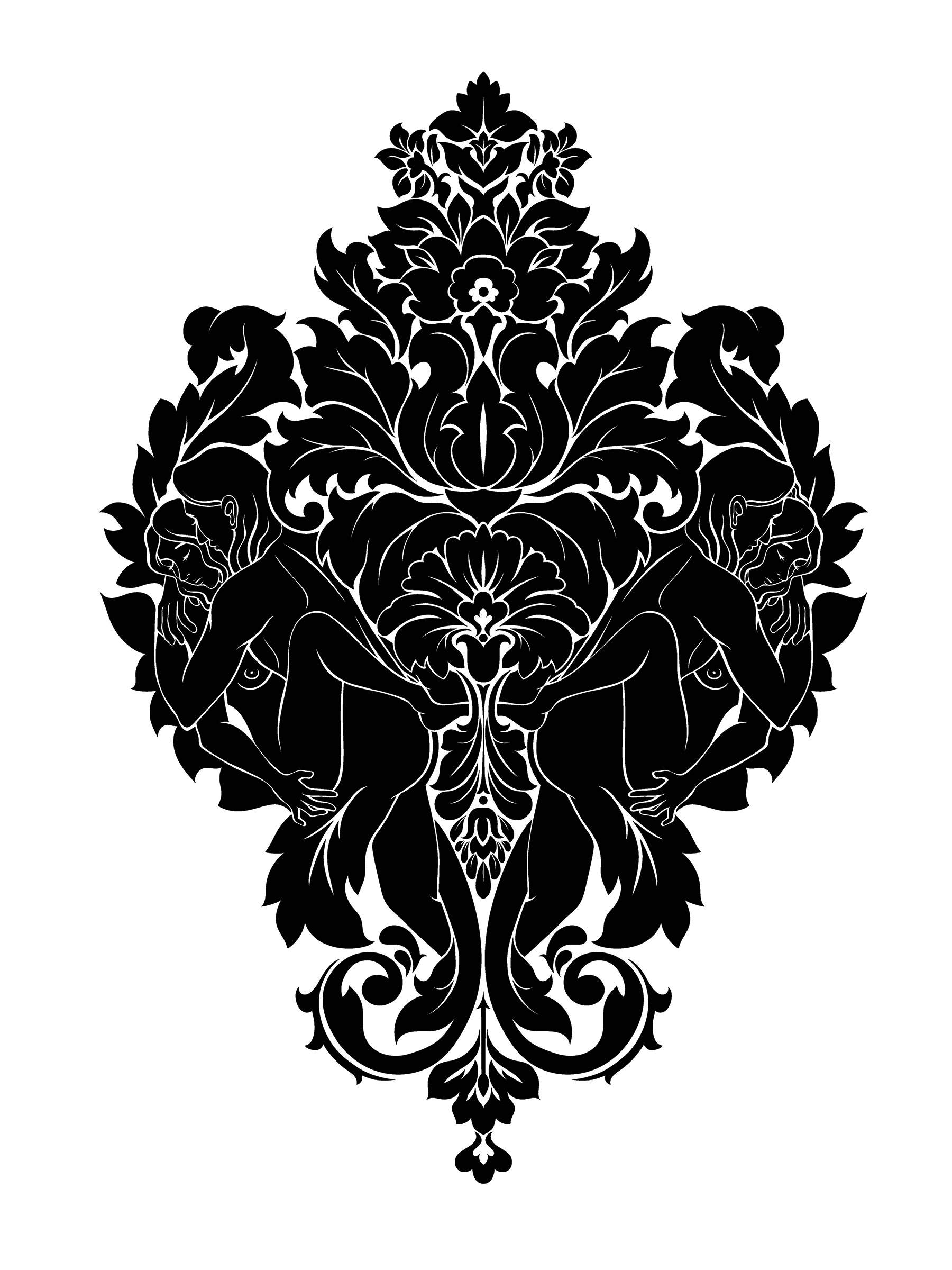

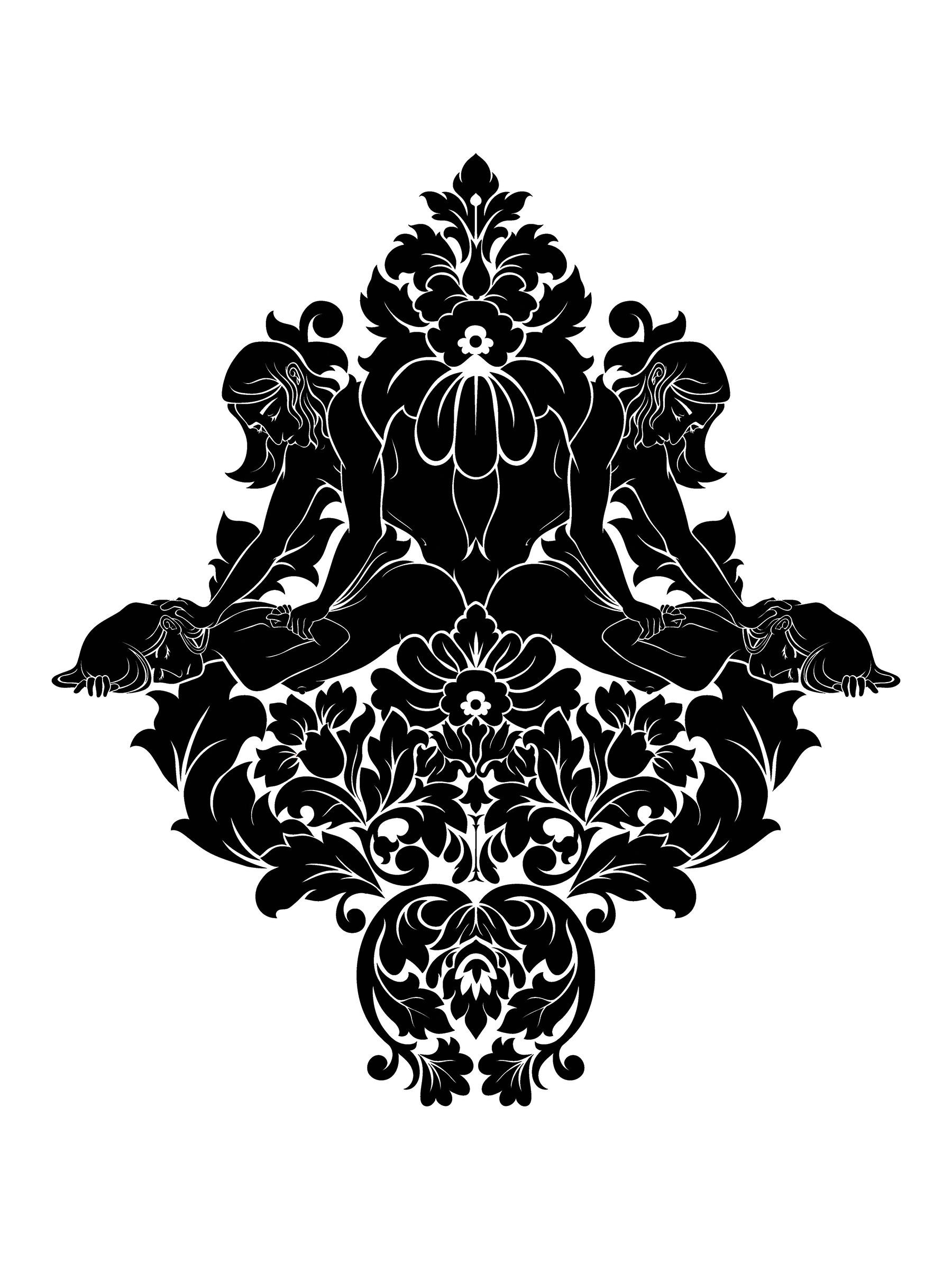

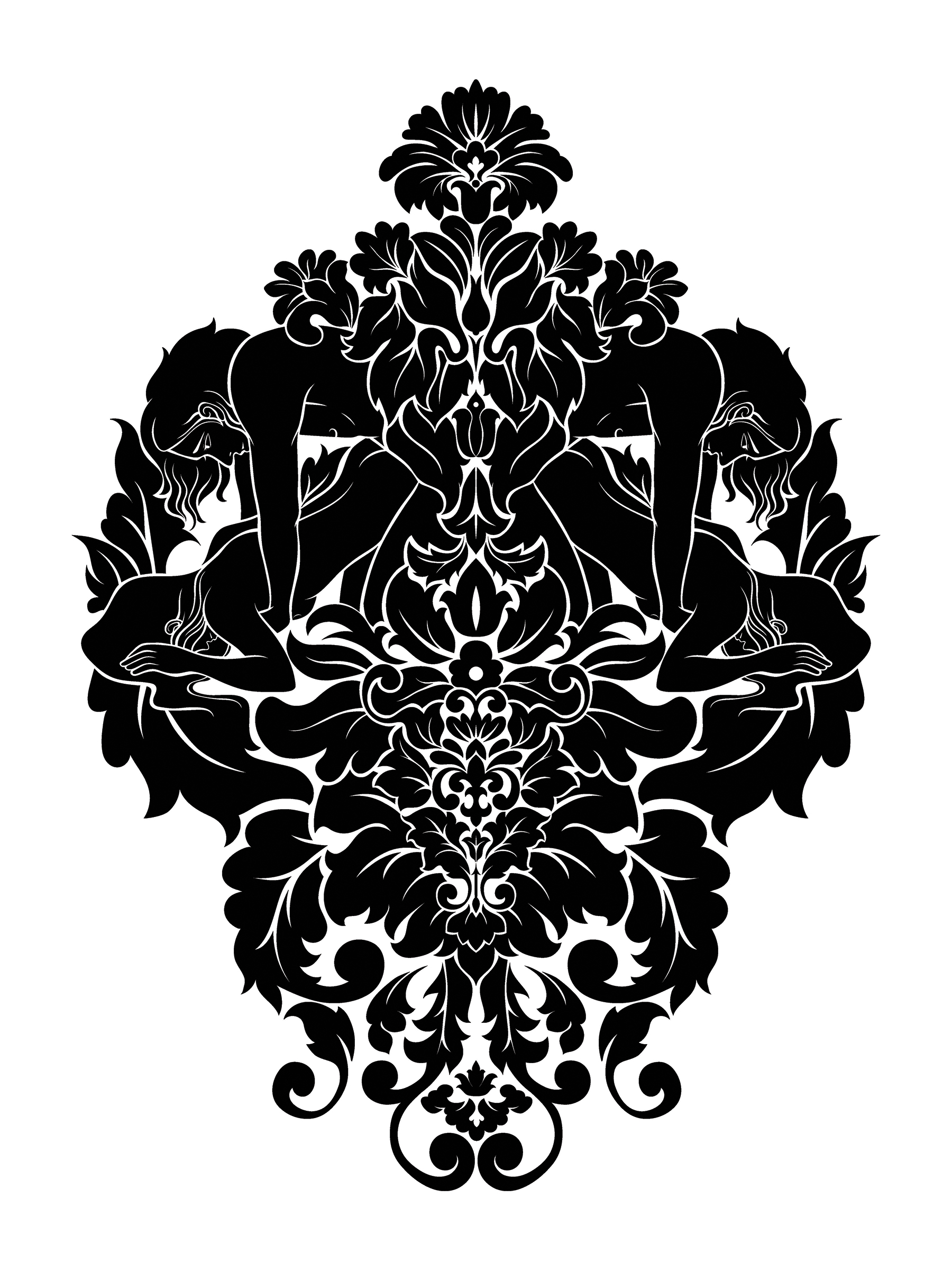

These Violent Delights

In These Violent Delights, bodies entwine with one another, and with the foliage that surrounds them. At first hidden within patterns inspired by the decadent images of baroque Italian damask silks, the figures become apparent upon closer look, revealing erotic scenes of pleasure and violence.

Though the work’s motifs may be viewed individually, its presentation as a larger pattern demands it be considered as a whole. The content of one scene bleeds into the next, creating a tapestry of interwoven intimacy and transgression, wherein the barriers between individuals’ bodies are broken apart, be it by will or by force. This is a space defined by liminality and dissonance, where brutality and vulnerability create a union which is as uncanny as it is inevitable. I cannot conceive of a sexuality without violence at its core, nor can I conceive of a loving partnership without the death of the individually-delineated self. To be with another—to love another—is to die.

By placing these images on the gallery glass, I obscure the view into the gallery space, creating a partition between what is “within” and “without.” The threshold between signifies my transformation of the space within into a place of my own design. Inside the gallery space, I perform a ritual of washing the hands of anyone who approaches me, as an act of intimacy and submission. As I kneel before my participants, the shadows of the patterns I created drape over us all, unifying the images and the ritual within.

Kyle Herrera

Photography, MFA ’20

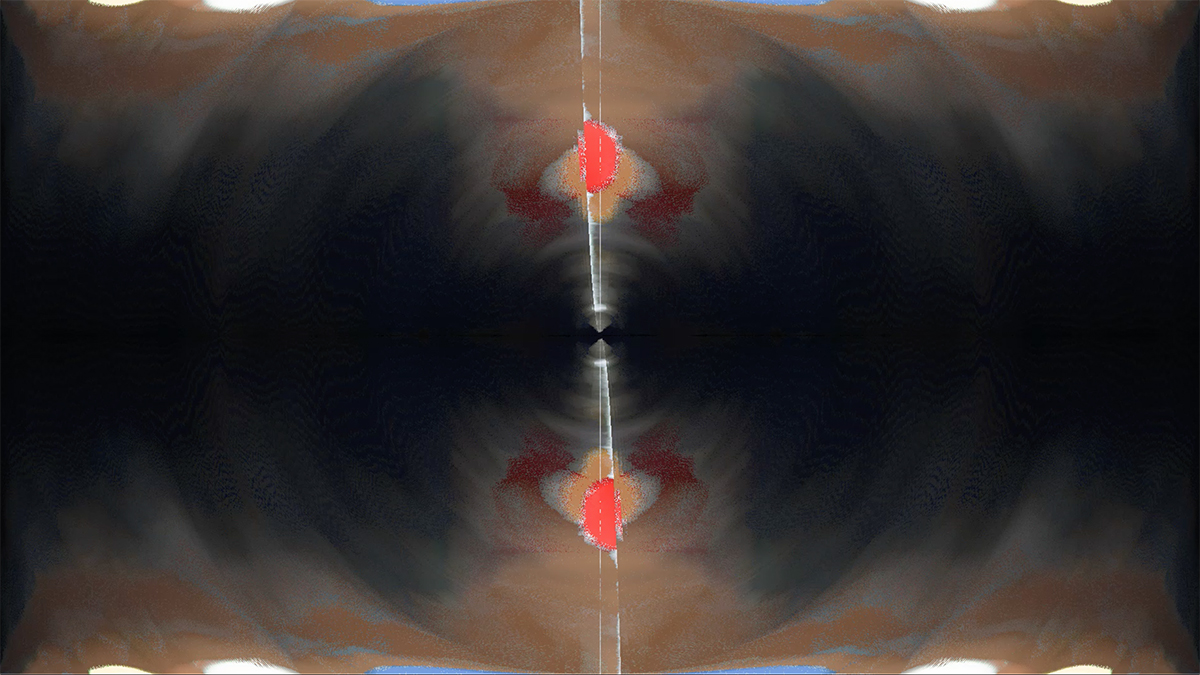

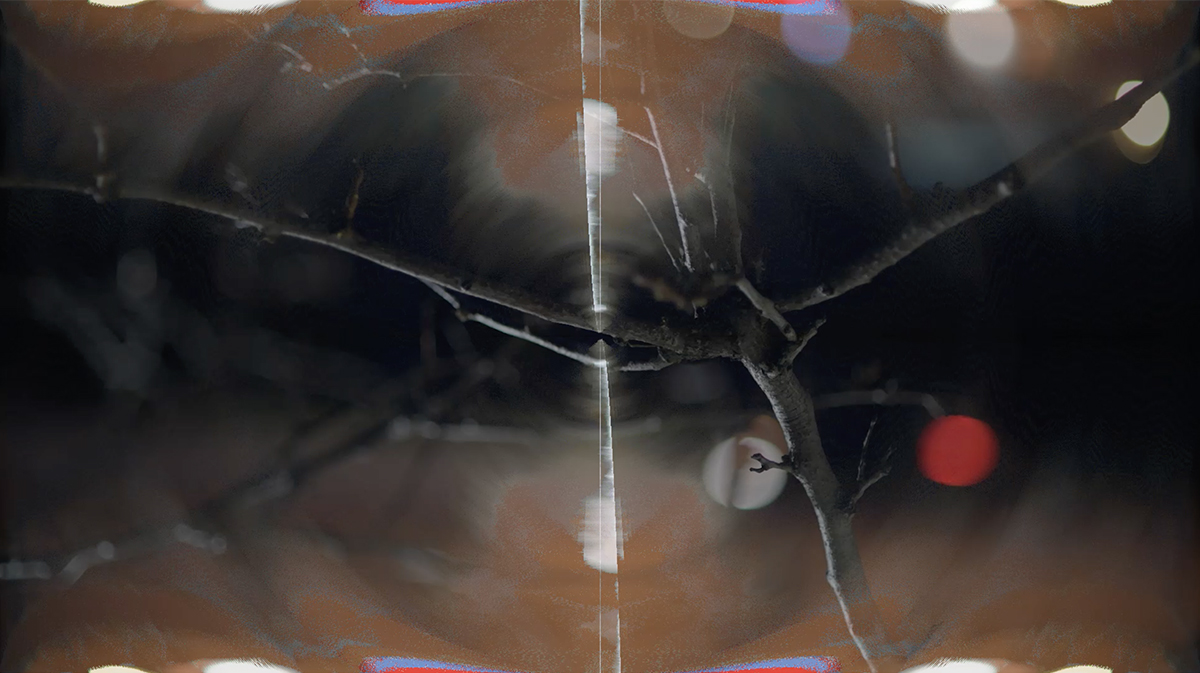

Only Days

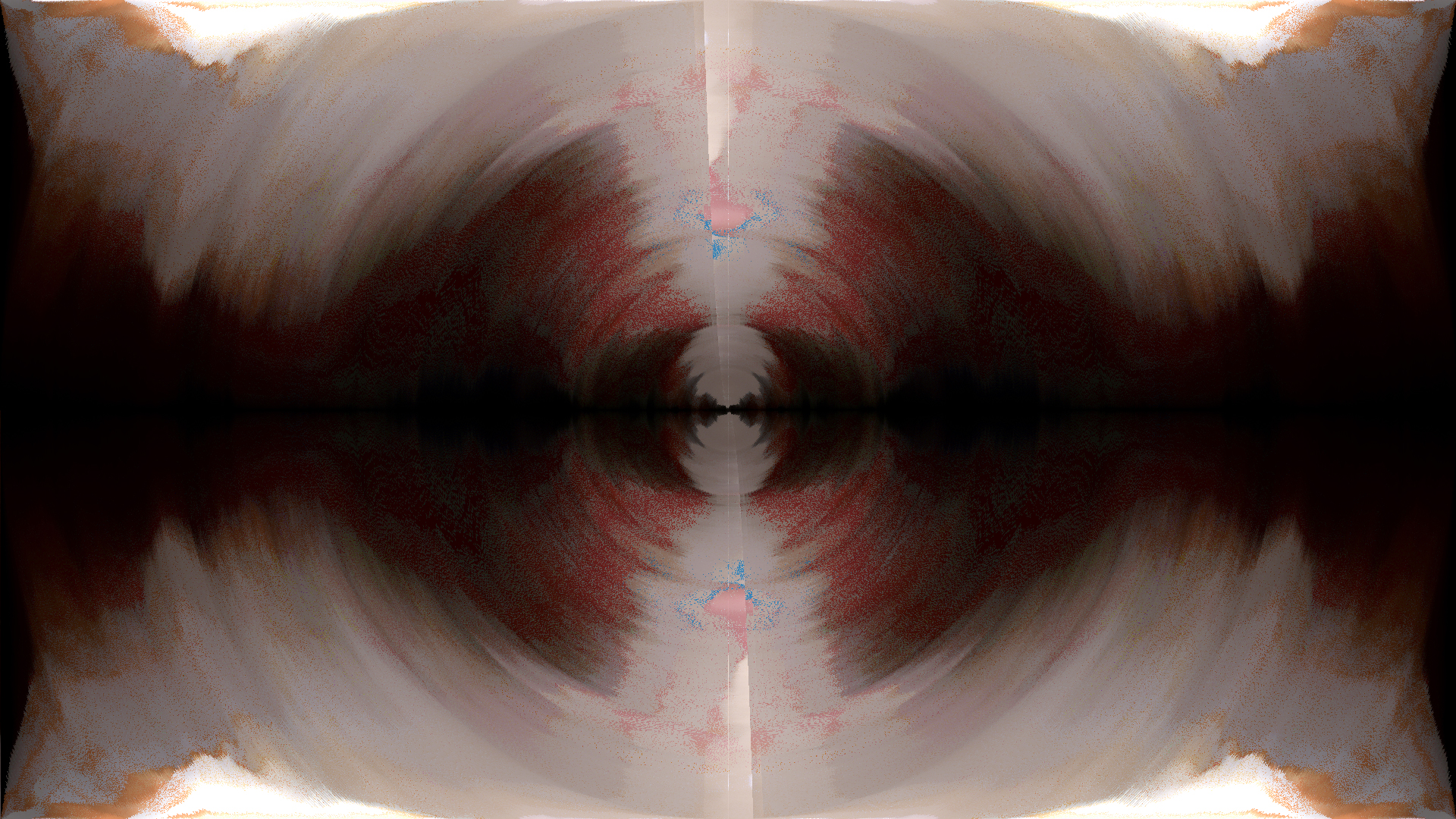

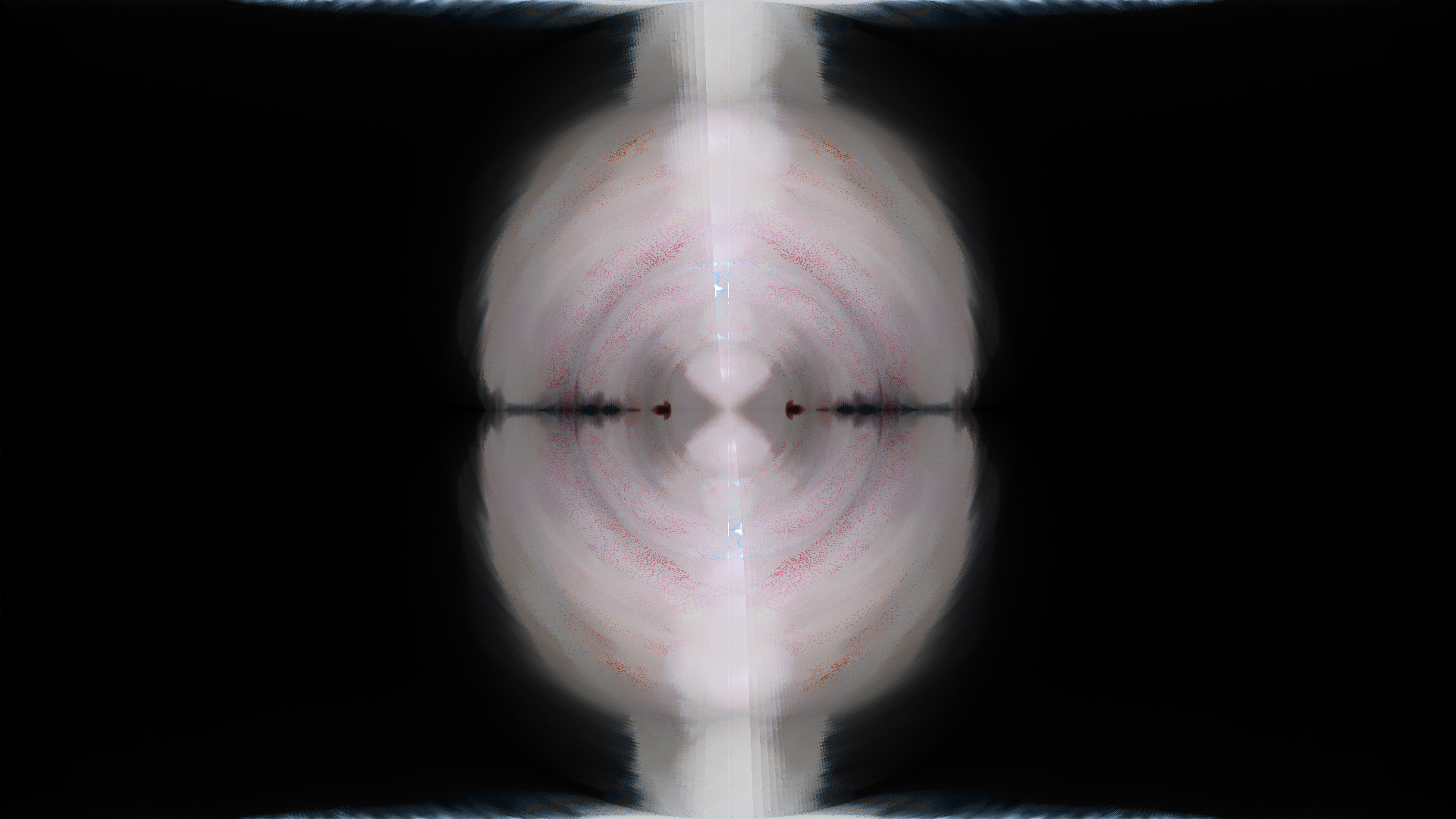

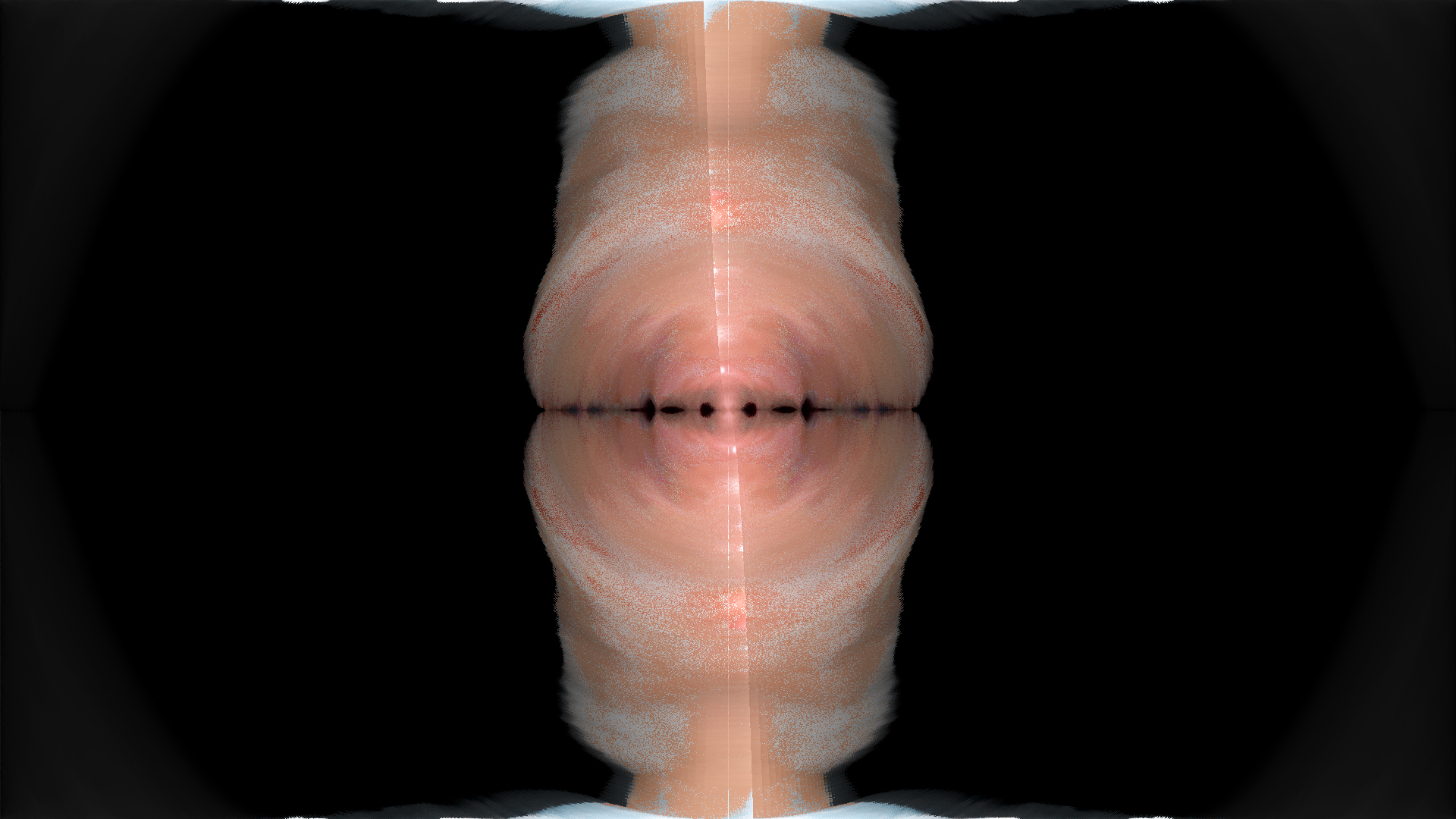

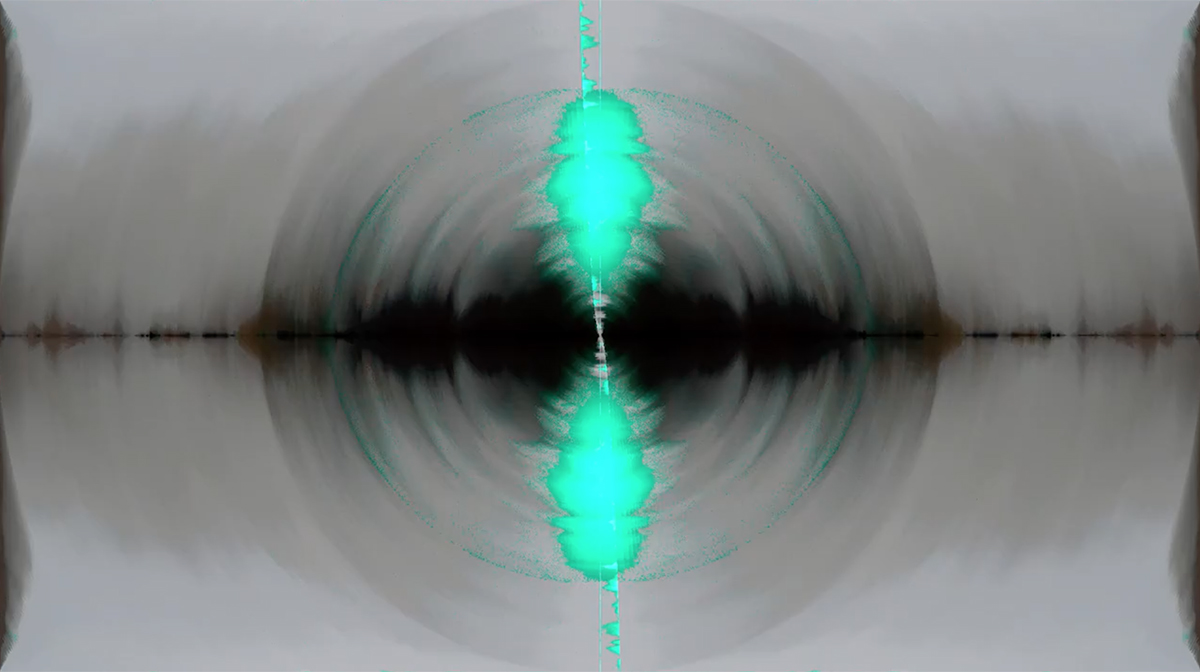

My work deals with anxiety, loss, and desire for meaning. I deploy digitally-processed imagery and sound as proxies for the mind and the body under duress, crafting narratives of survival and healing. This is a humanistic effort in which the viewer is offered validation and encouragement through a technological medium, thereby pursuing spiritual goals—transcendence, ontological comfort—while retaining a materialist conception of reality.

Only Days is a response to loss. In it actors perform a narrative which begins in comfortable naiveté, descends to existential dread, and finally arrives at peace. Their initial turn from contentment to unease is precipitated by the abstraction of their digital image, conjuring grotesque distortions of the body and appearing to mock their despair. Here the medium asserts itself as a stand-in for mortality, trapping its subjects within itself and refusing rationalization.

Relief is found in the subjects’ direct engagement with the artifice of the medium, as they trade speech and song with the work’s non-diegetic layers of sound, thereby seeing, accepting, and working within the limitations of their reality. Simultaneously they turn towards fundamental aspects of the human experience—connections with nature and time, and loving interactions with others.

Throughout this process, the same digital abstraction persists. Close inspection reveals that the abstracted image does not destroy the original, it simply rearranges its components, without any loss, into a coherent patterned whole. Each frame’s pixels are rendered as atoms reconstituting new living and non-living material alike. Rather than negate the experiences of its subjects, the reality of this reconfiguration serves to complement and enhance them. Likewise one’s awareness of the facts of mortality—existing only temporarily within a finite space, beholden to an incomplete understanding of the self and the world—need not diminish the value of our shared presence.

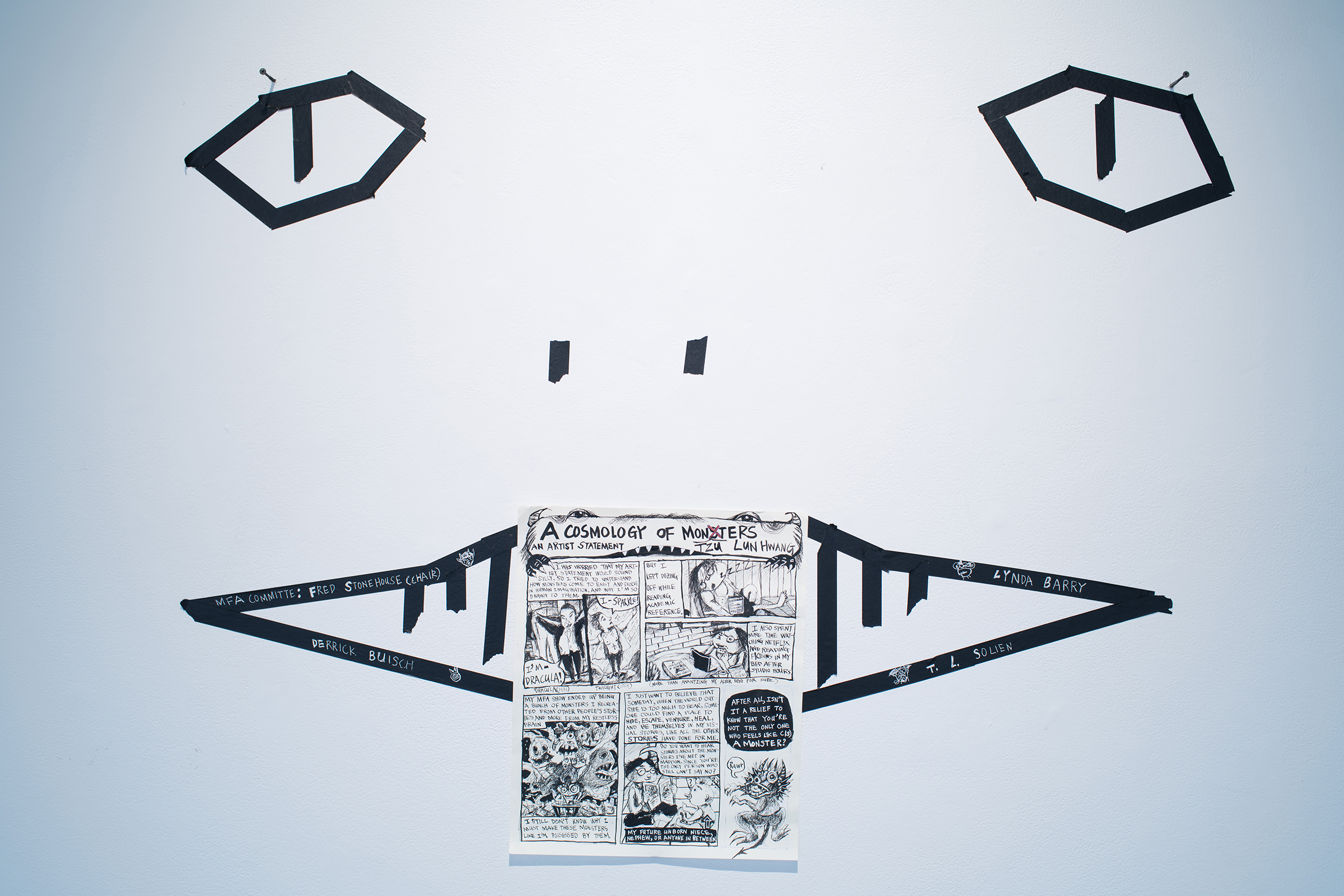

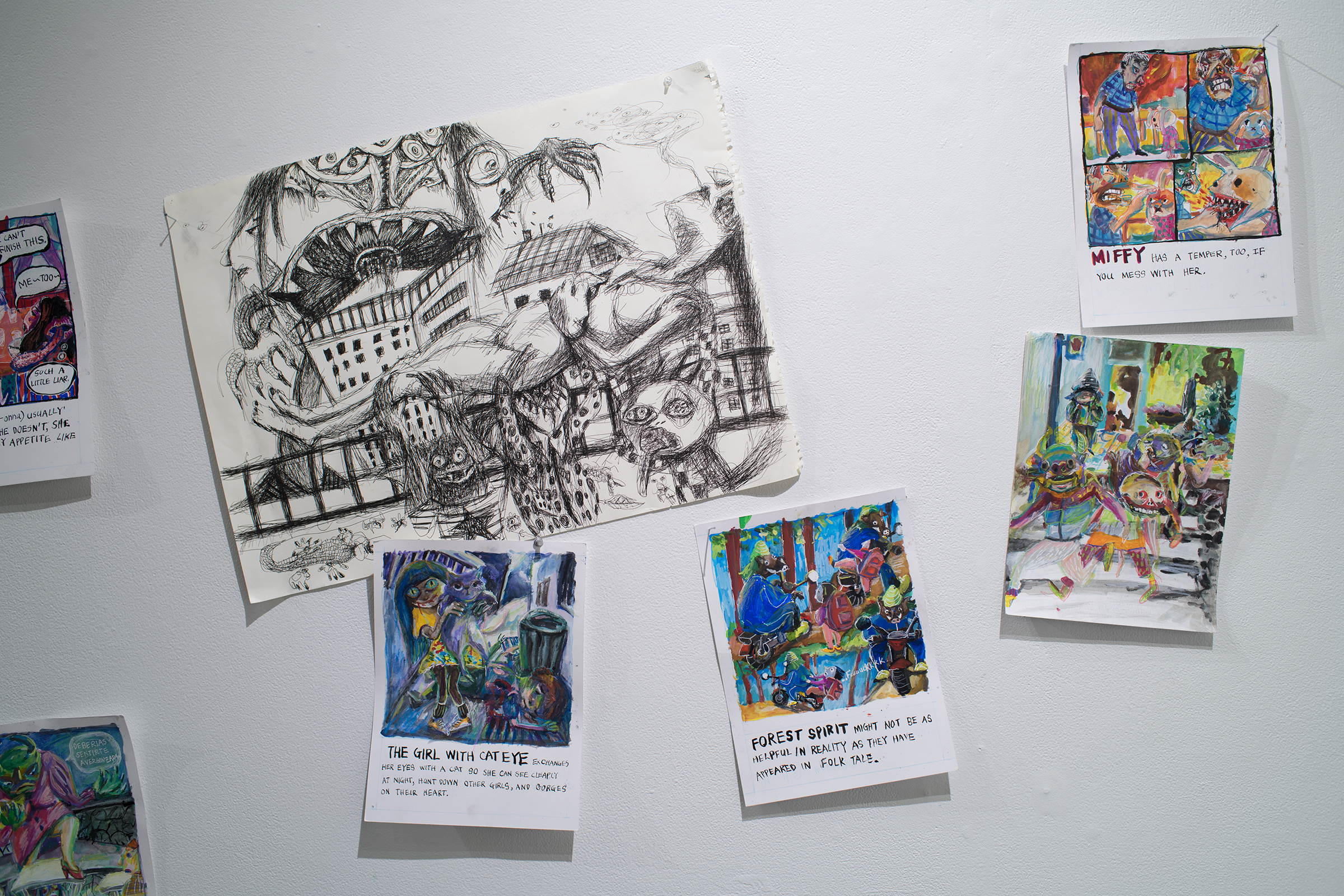

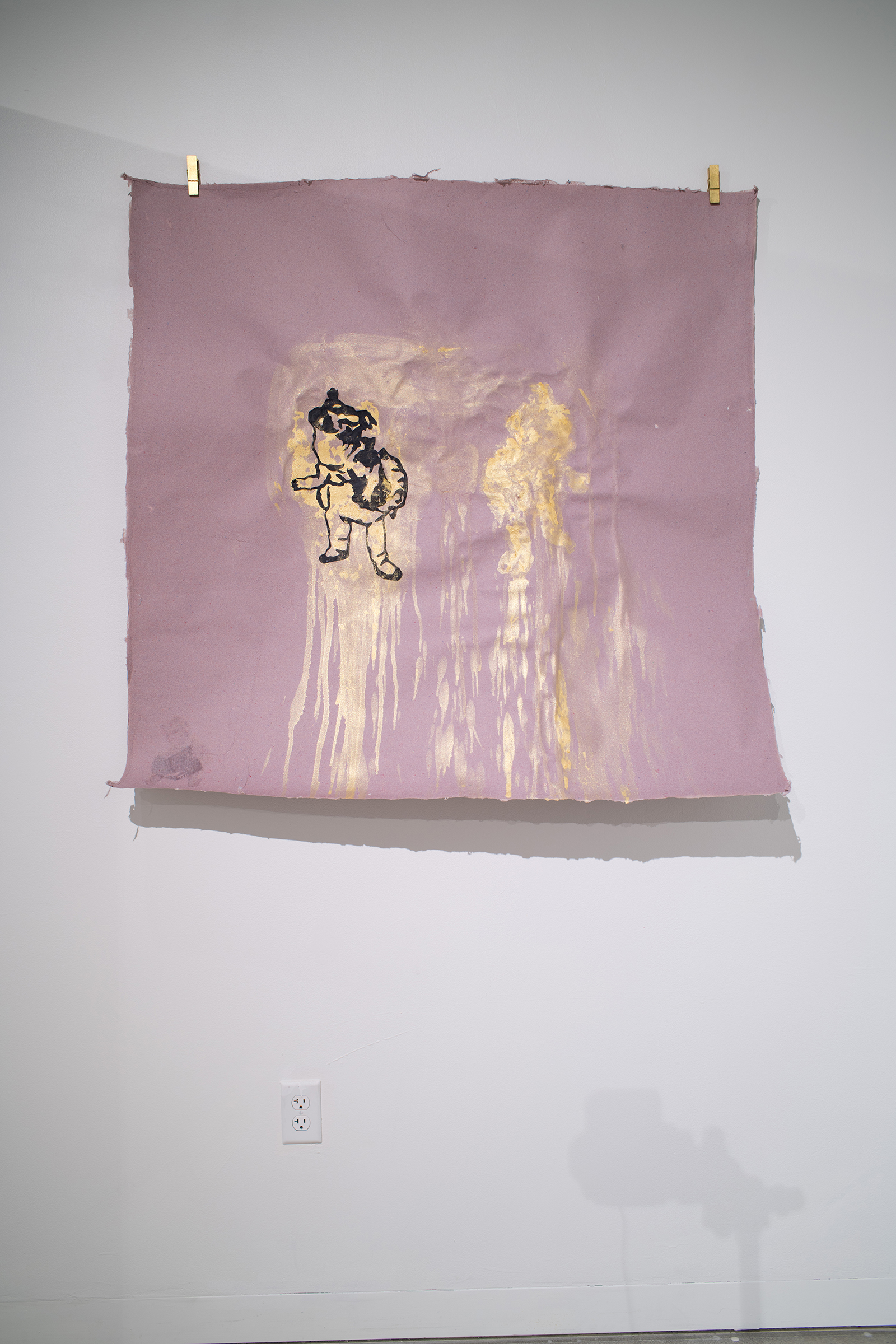

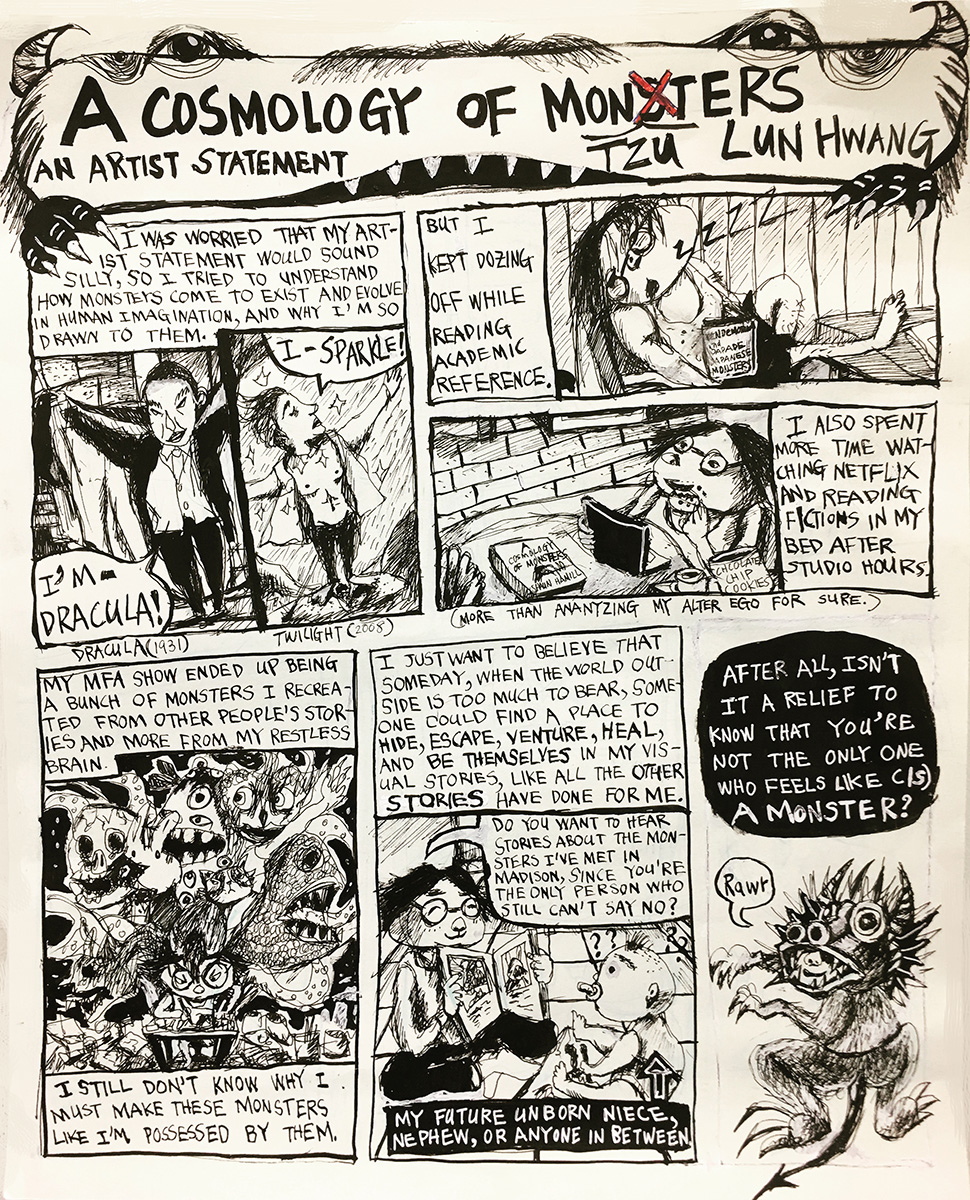

Tzu Lun Hwang

Painting & Drawing, MFA ’20

A Cosmology of Monsters

I was worried that my artist statement would sound silly, so I tried to understand how monsters come to exist and evolve in human imagination, and why I’m so drawn to them. [Two comic panels of Dracula 1931 panel of a figure in a suit and cape with arms and cape raised, saying, “I’m Dracula!” Followed by Twilight 2008 comic panel of a figure standing outside in the sun with shirt unbuttoned and open, surrounded by sparkles saying, “I sparkle!”]

But I kept dozing off while reading academic reference. [Next panel of the artist reclining with a book in hand, asleep.]

I also spent more time watching Netflix and reading fictions in my bed after studio hours. (More than analyzing my alter ego for sure.) [Comic panel of the artist in bed, snacking on chocolate chip cookies, with an open laptop and a closed book on their lap.]

My MFA show ended up being a bunch of monsters I recreated from other people’s stories and more from my restless brain. [Comic panel of the artist drawing, surrounded by art supplies to either side, and a cloud of monsters emerging from their head.] I still don’t know why I must make these monsters like I’m possessed by them.

I just want to believe that someday, when the world outside is too much to bear, someone could find a place to hide, escape, venture, heal, and be themselves in my visual stories, like all the other stories have done for me. [Comic panel of the artist showing their comic zine A Cosmology of Monsters to a baby with question marks hovering over their head, labeled “My future unborn niece, nephew, or anyone in between.” The artist is saying, “Do you want to hear stories about the monsters I’ve met in Madison, since you’re the only person who can’t say no?”]

After all, isn’t it a relief to know that you’re not the only one who feels like (is) a monster? [Final comic panel of the artist wearing a monster costume, saying, “Rawr.”]

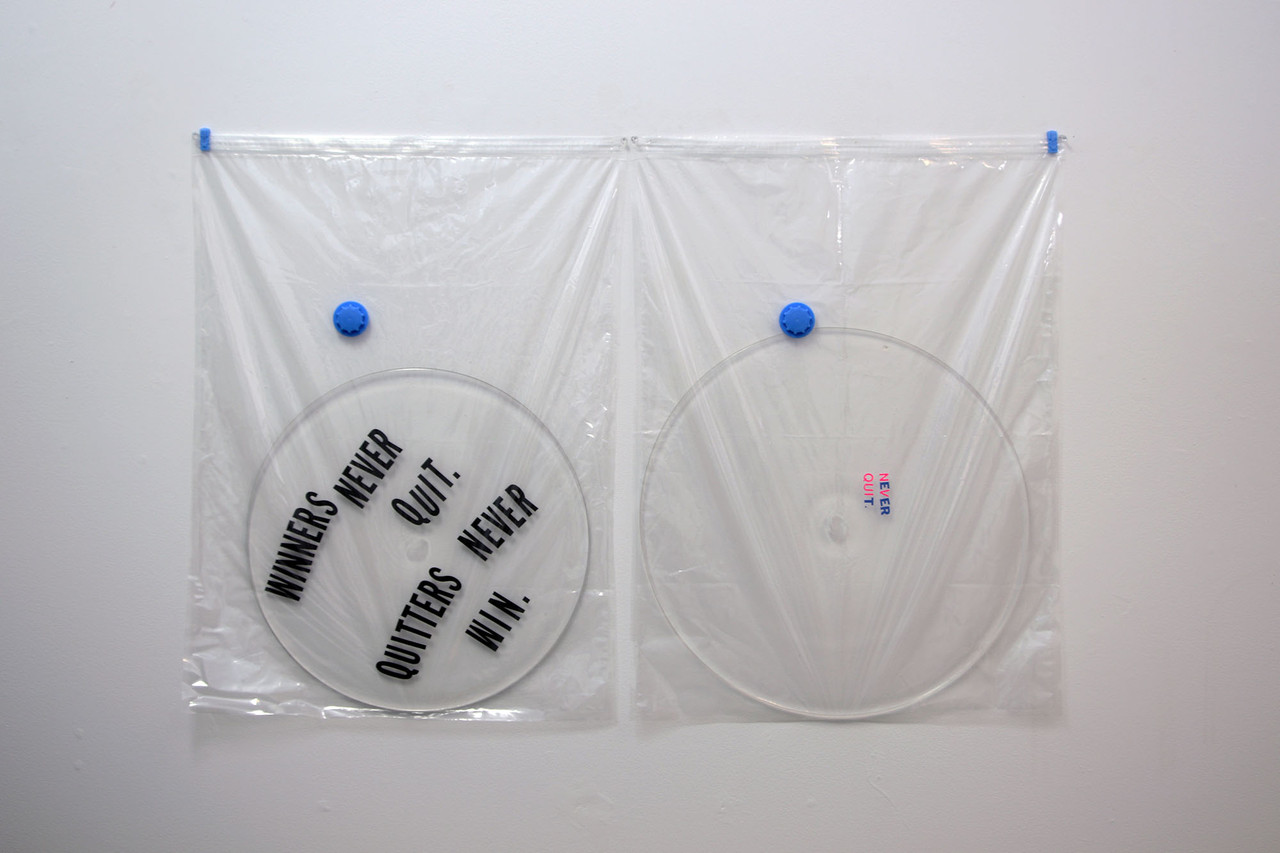

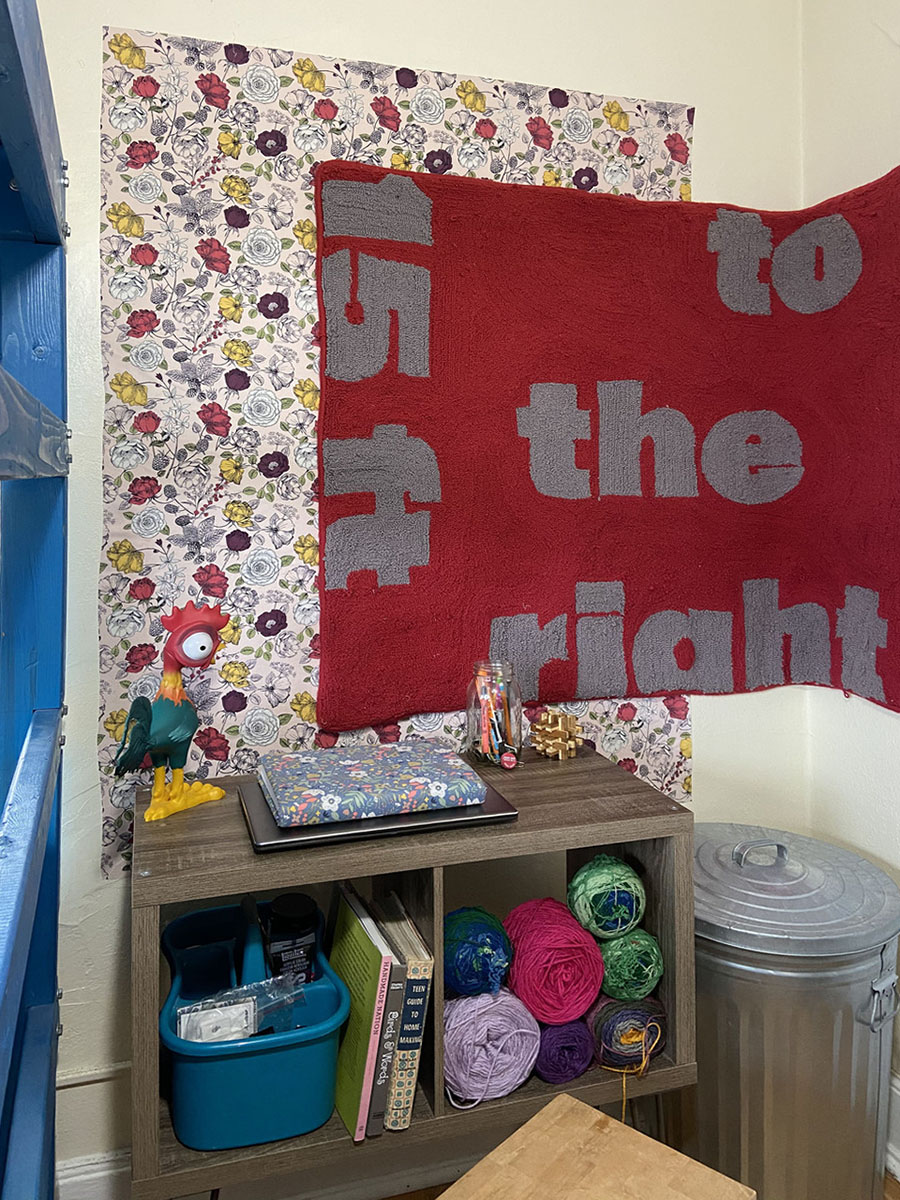

Jodi Robertson

Sculpture, MFA ’20

Come on in

My grandpa Jack would sit at his kitchen table every morning and drink his cups of coffee. He was known for this simple act. When friends and family drove by, they knew there was always a cup of coffee and conversation waiting if they so choose. As an adult I realize the example he had set for the conversation were always in response to the person and the information that sat before him. It was through him that I learned the value of kindness and the space it can help to create, that allows for open exchange of ideas and opinions.

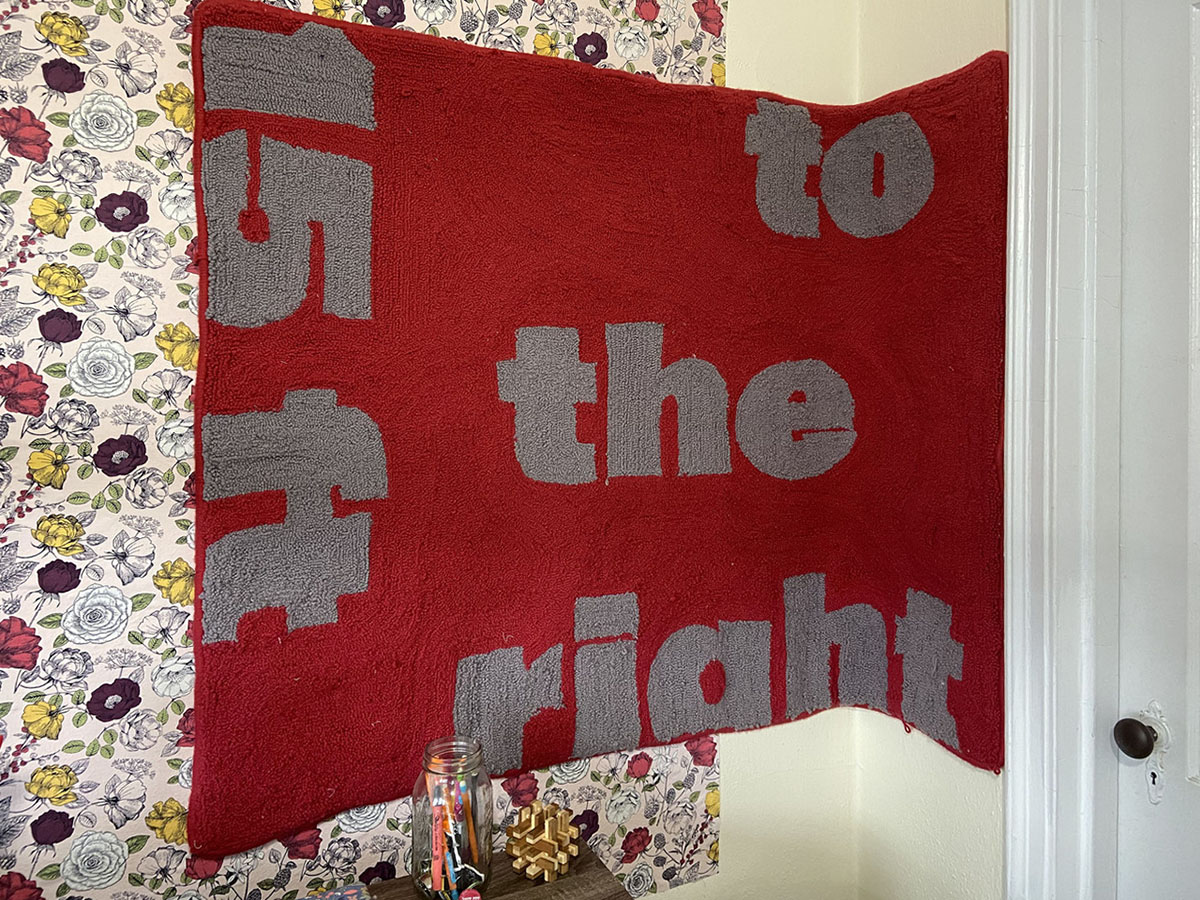

This show is intended to represent the idea and value of good conversation. I have created spaces with the intent to be welcoming and inviting. The example of the table stands as a metaphor to the conversation I witness as a child, yet sits empty to represent the polarizing culture we are living in. This culture has created an environment that feeds off aggressive and defense behavior making it more of a struggle to have an open exchange of differing views. The assertive phrases that line the walls are there as a reminder to value a willingness to hear the others’ views, and the importance to be respectful during an exchange, striving to follow the example my grandfather set.

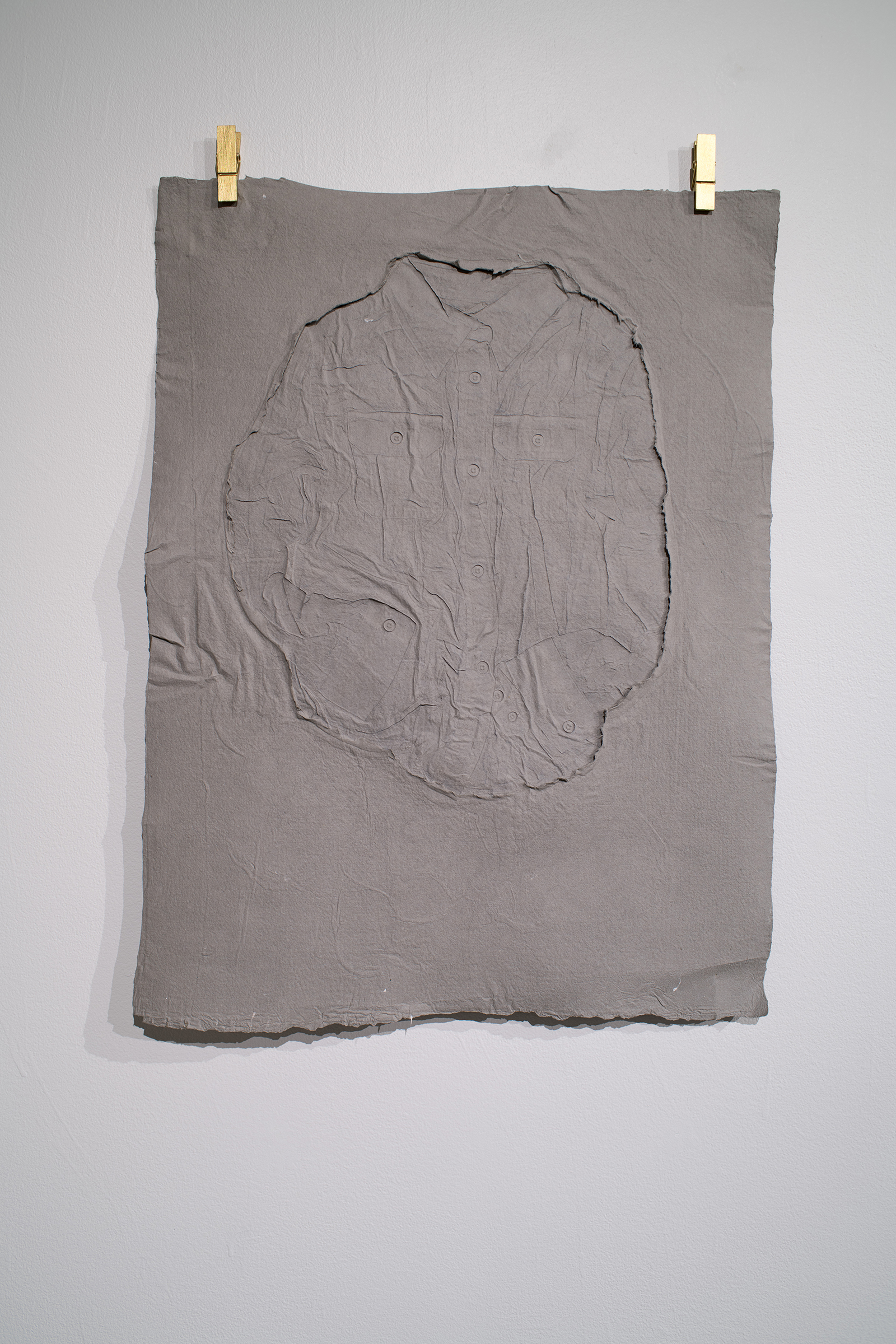

Tim Jorgensen

Sculpture, MFA ’20

My Father’s Son

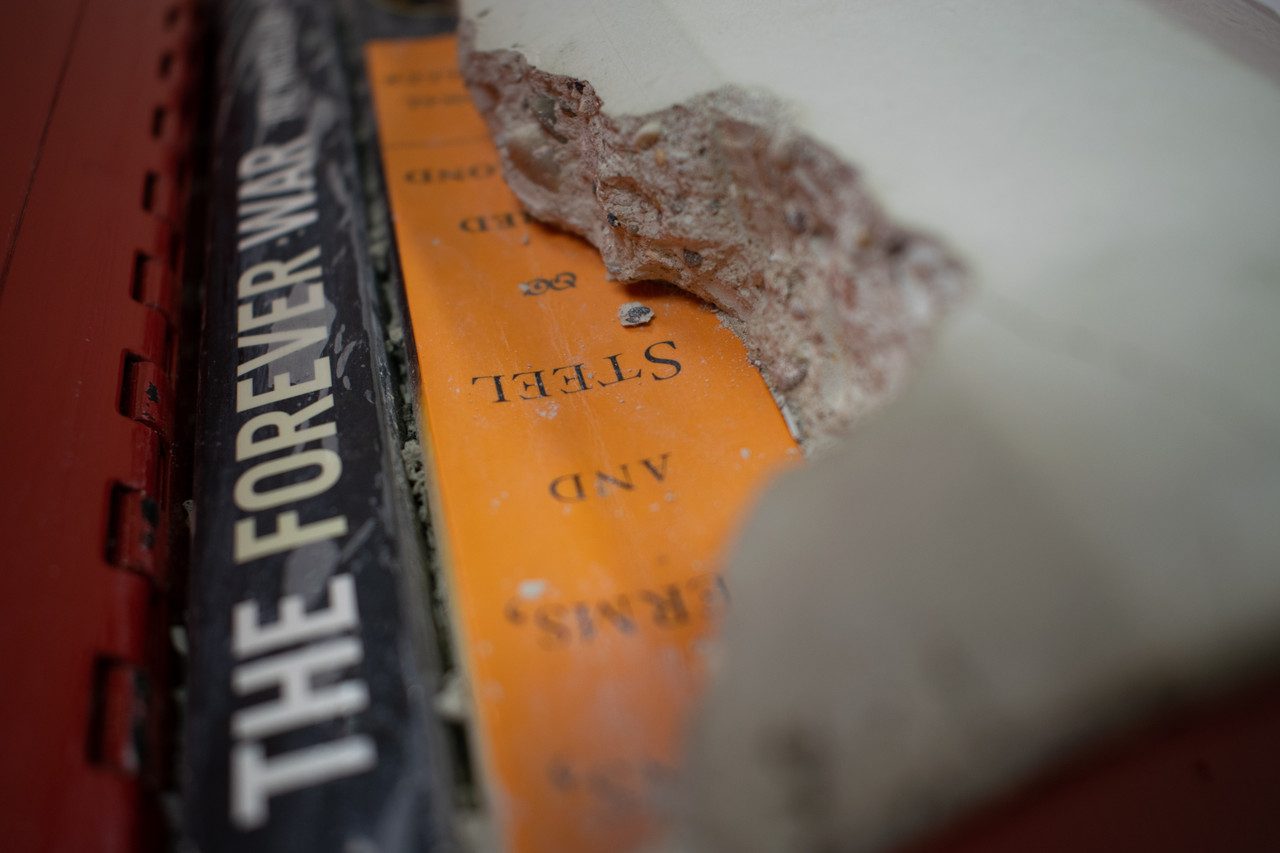

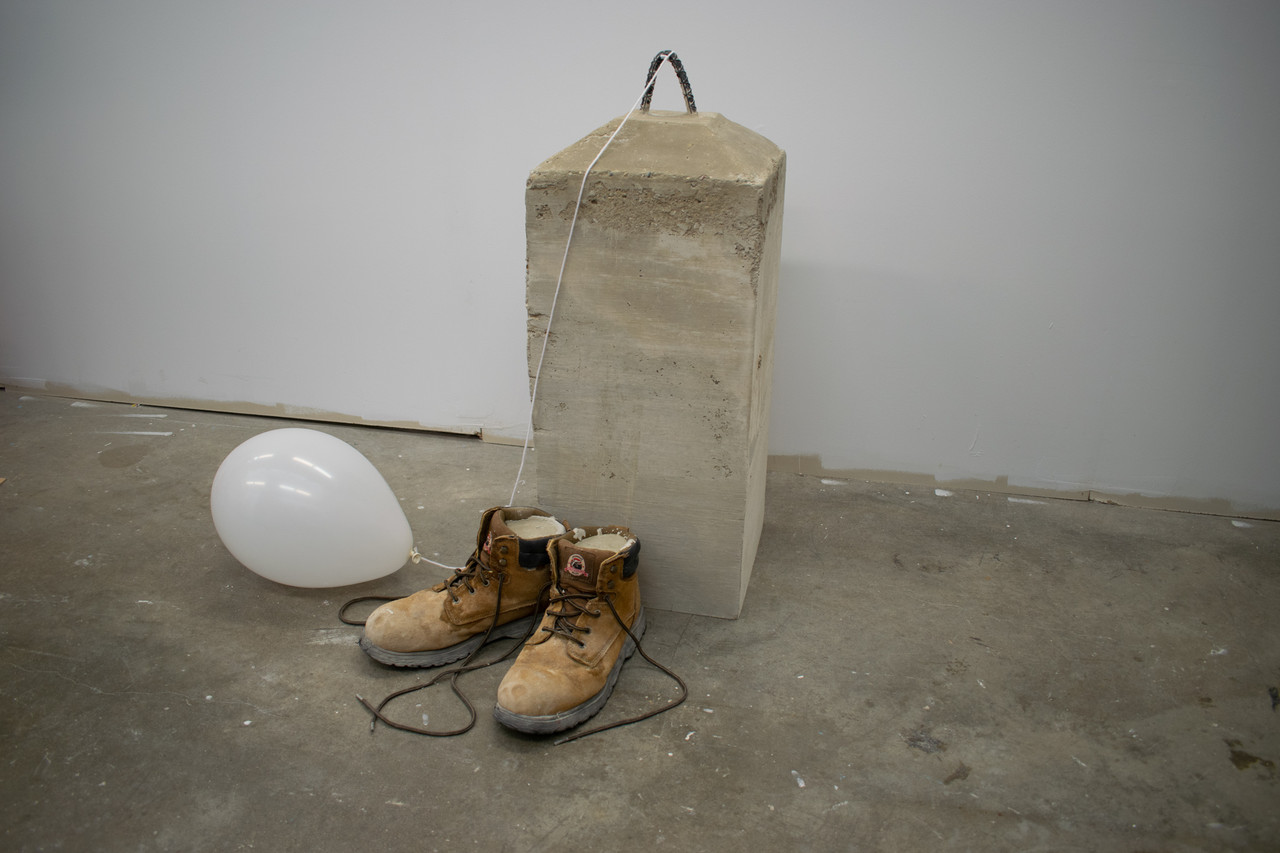

How do we evaluate the weight of expectation? As a child, I felt influenced to adopt favorable traits from my parents and mentors. Rationalizing my behavior through other’s reactions in order to gain an understanding of what it means to fulfill my role, in turn shaping my personal identity through these exchanges. The defining characteristics that play into whether I contribute to society or become self-centered. How I act and deal with loss. How I treat others. The accumulation forms constraints around my personality, becoming the weight and pressure of expectation, hindering my own personal development.

The embedded objects in my new work signify notions of masculinity and establish meaning through their associations with my own childhood, with my own coming of age. These are objects that remind me of feelings and influences throughout my life. These objects inform the foundation and framework of what constitutes my personal ideas of manhood. For better or worse, these are the parts I’m made of. Reconciling these embedded archetypes with a desire to forge my own particular path to who I am today, my father’s son.

Stacy Lynne Motte

Woodworking, MFA ’20

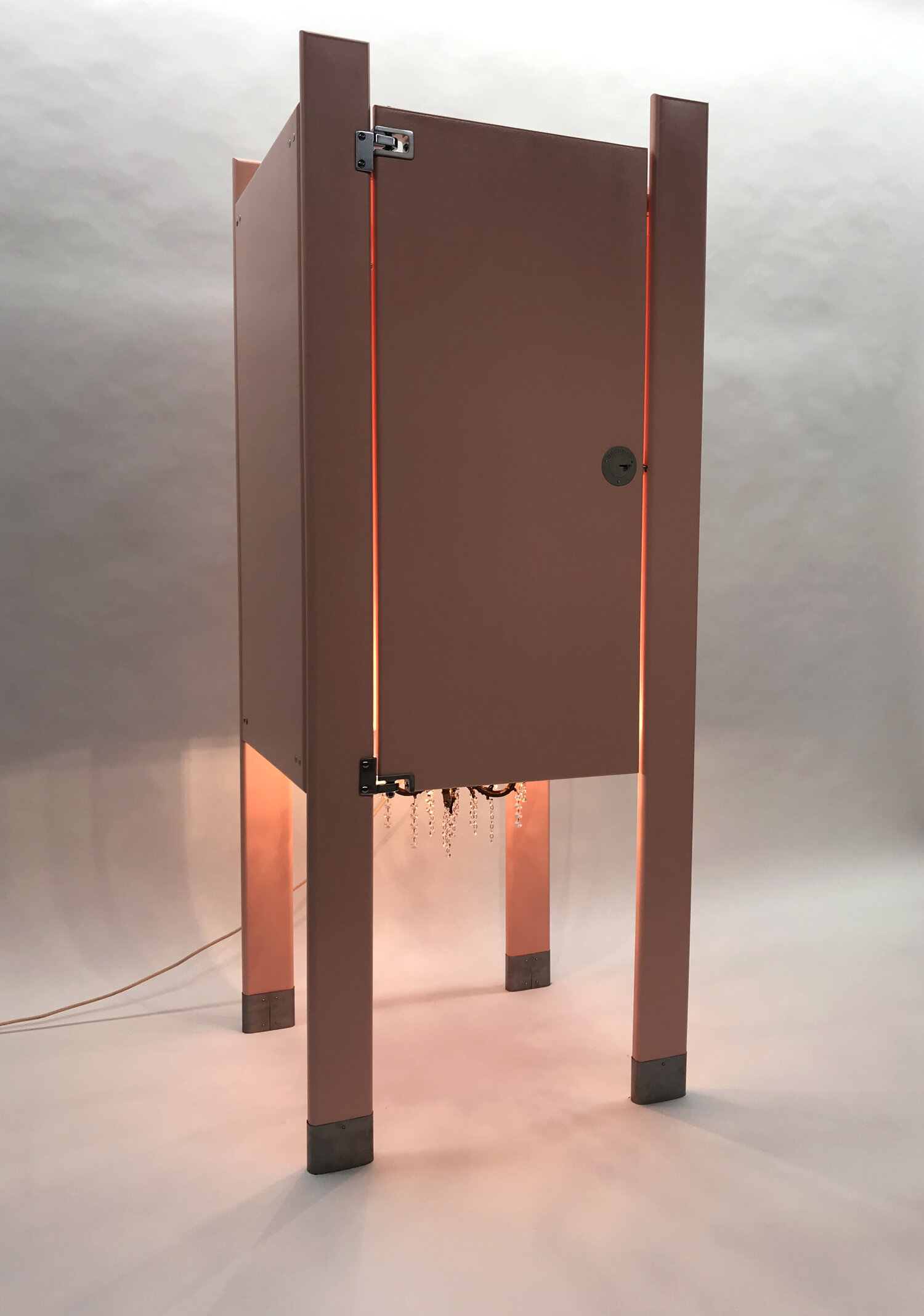

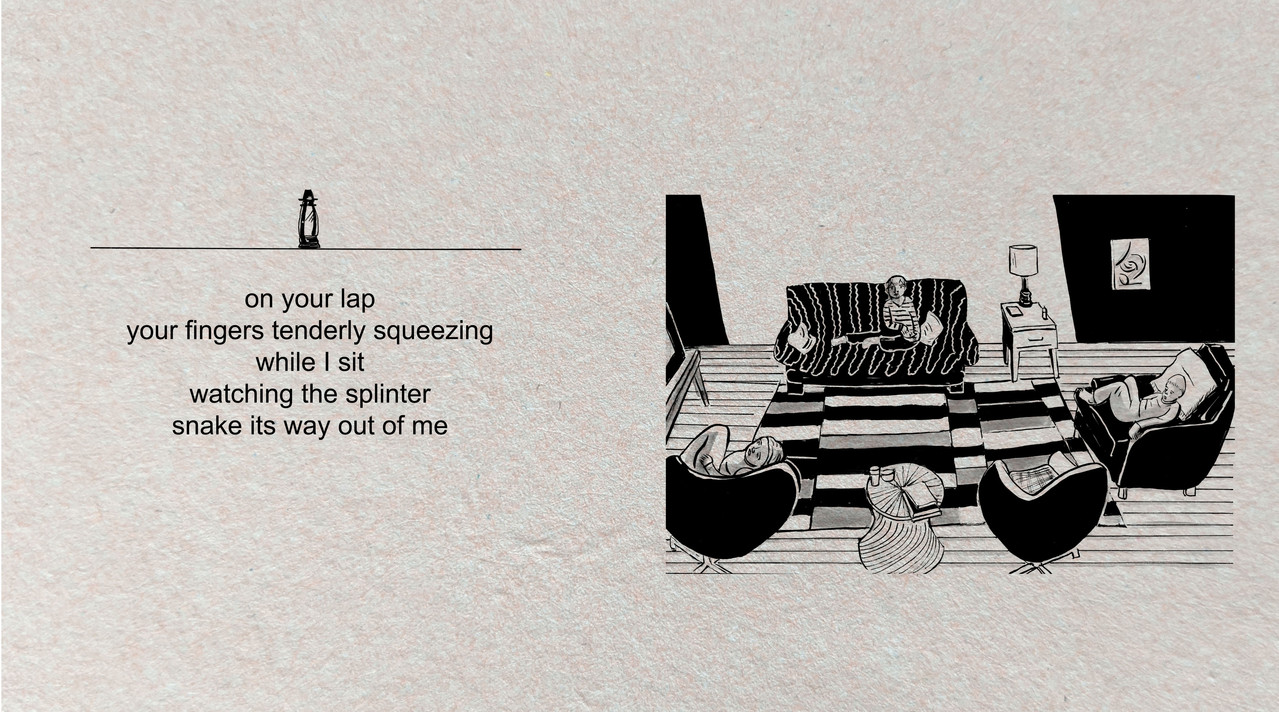

The Dangly Bits and other Vulnerable Encounters

My work explores femininity as a socially and culturally constructed concept with constraints on behavior that are alternately suffocating and comforting. By building a domestic space and filling it with delicate, quaint, and seemingly innocuous objects that misbehave, objects that are simultaneously luxurious and vile, I hope to challenge and complicate our associations with femininity. For me, The Dangly Bits and Other Vulnerable Encounters refers to that moment when you’ve laughed too loud, said something too provocative, sweated too much, or behaved in any other decidedly unfeminine fashion and immediately been made to regret it.

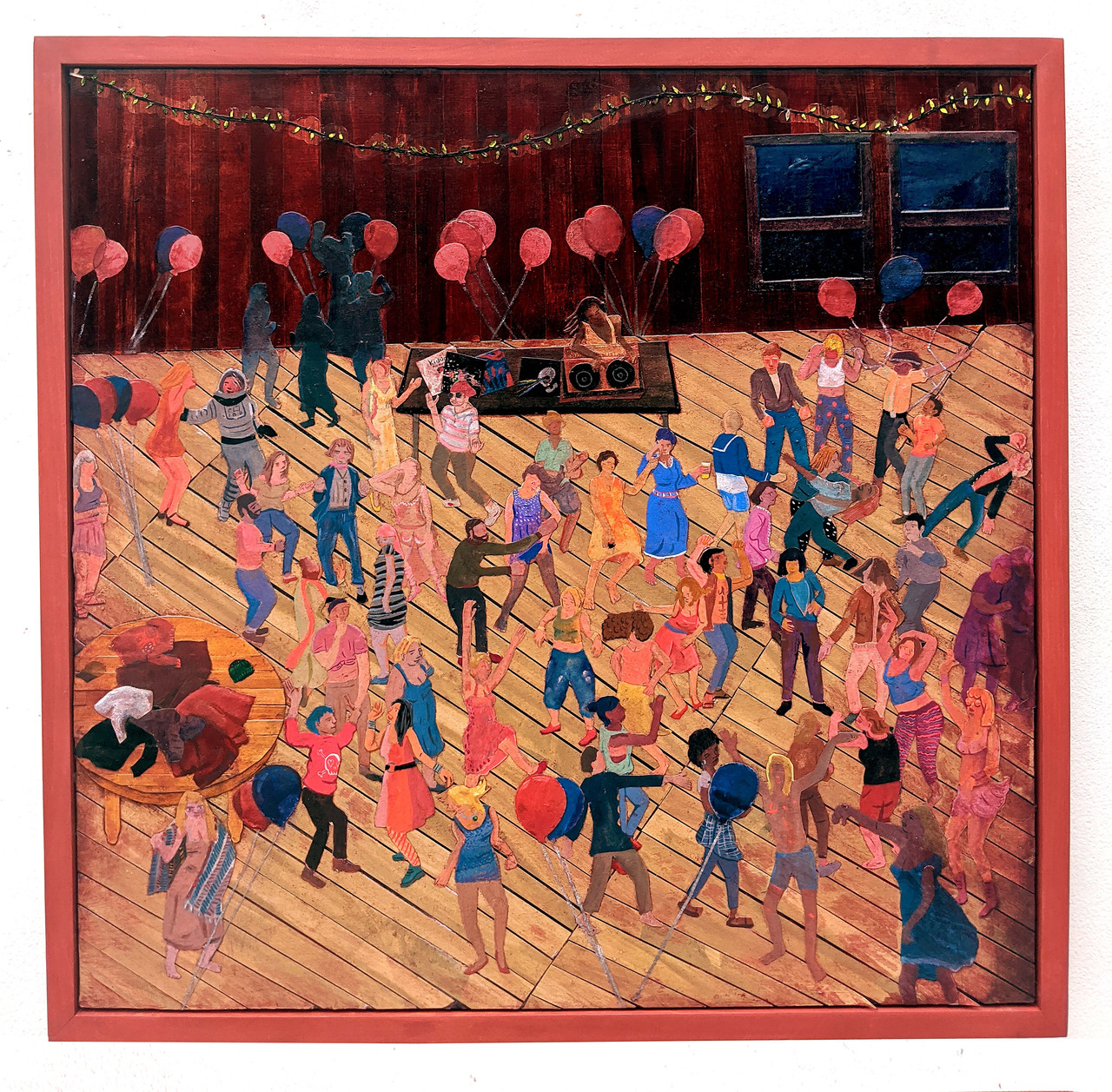

Solarpunk Surf Club

4D, MFA ’20

Græn R∞m

Græn R∞m is a public living room for utopian (re)creation. Guests are invited to read, rest, play, and socialize in a cozy, communal environment. The project takes its name from three different concepts of ‘the green room.’ In theater, music, and entertainment: a space to relax and socialize backstage; a room for artists and guests to prepare before, and retire after, a performance. In the White House: an artfully decorated state parlor used for intimate receptions and tea ceremonies. In surfing parlance: the sublime yet precarious space inside the barrel of a breaking wave.

Solarpunk Surf Club is an arts collective who create and curate egalitarian platforms for surfing the waves of still-possible worlds.

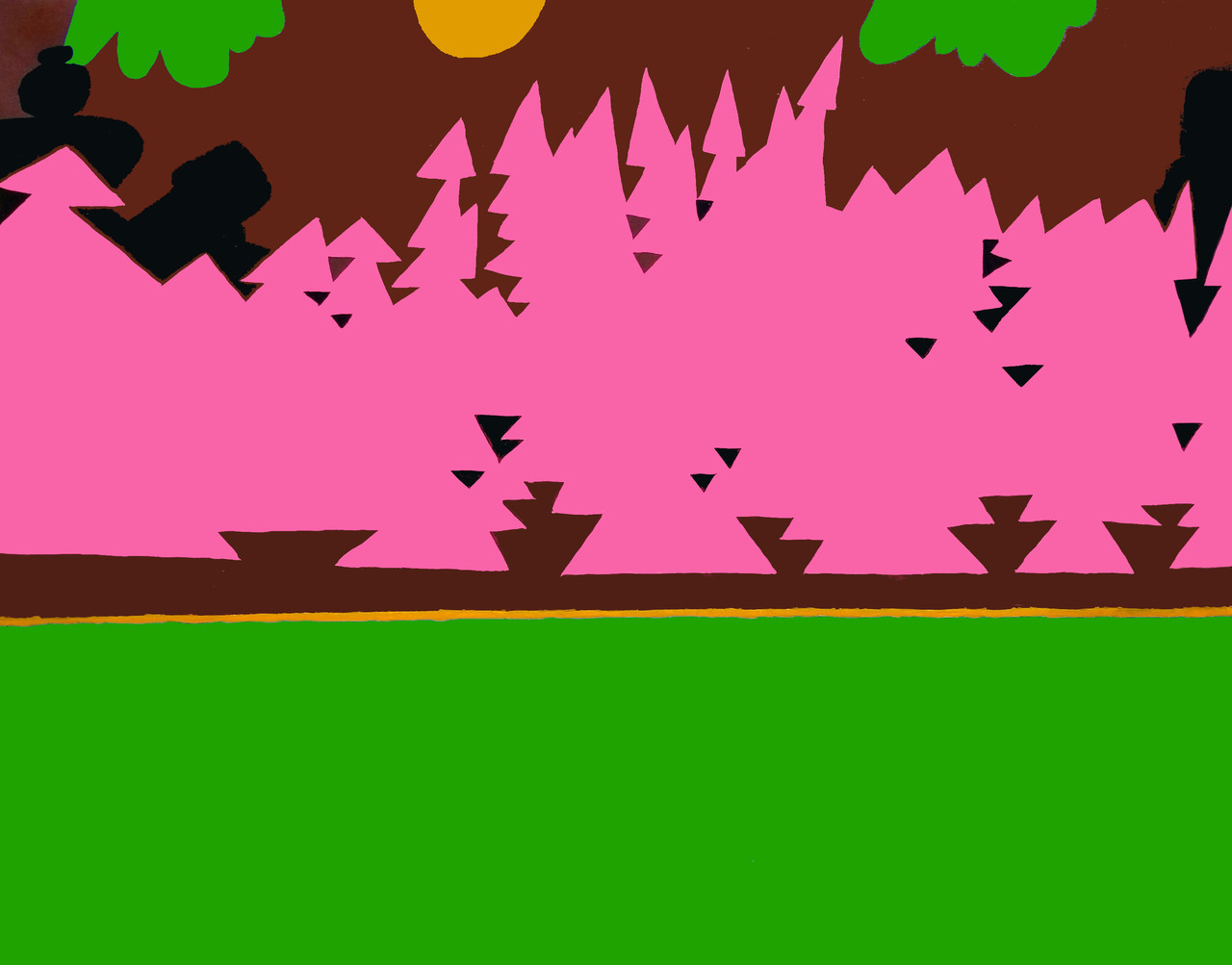

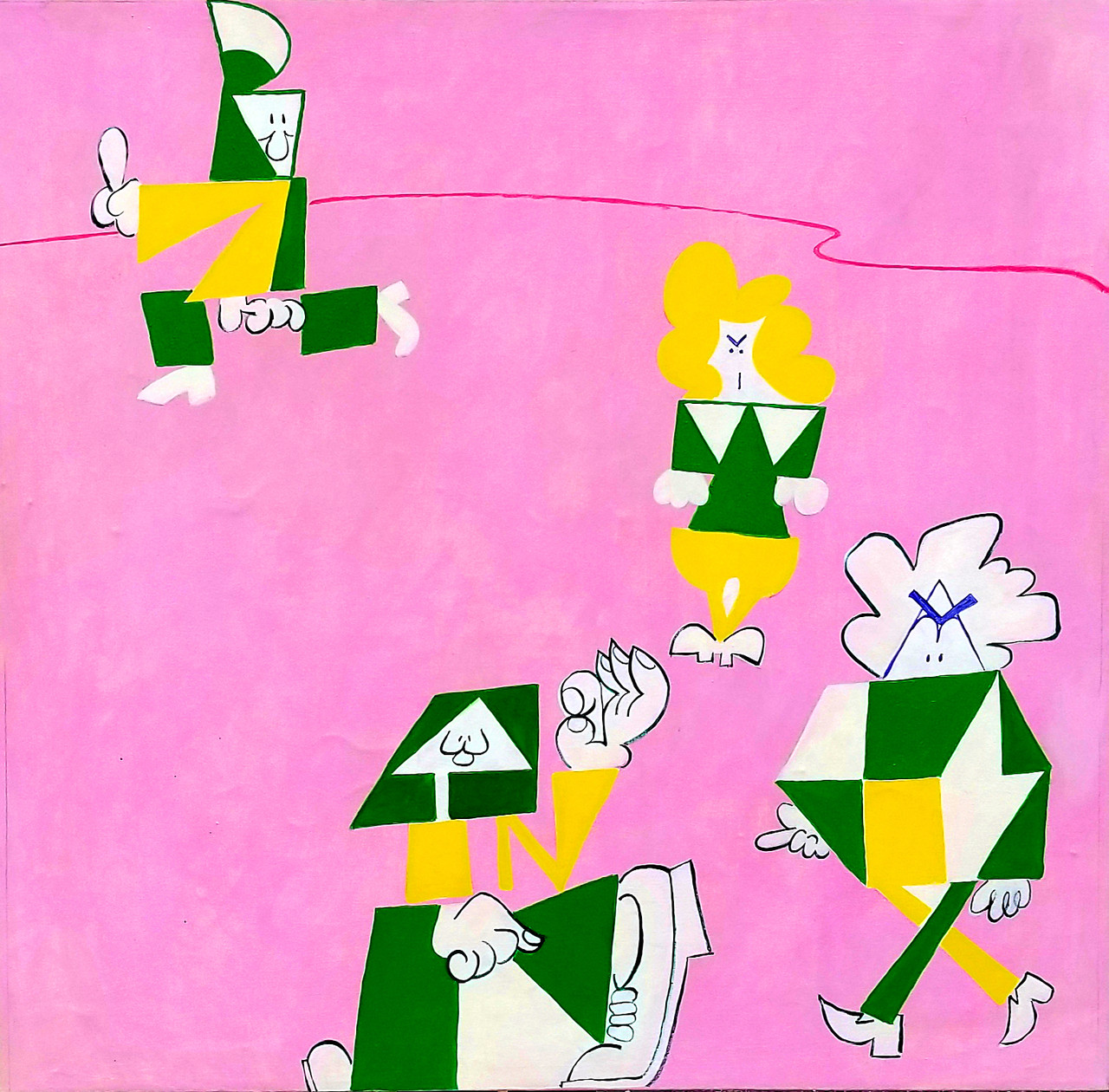

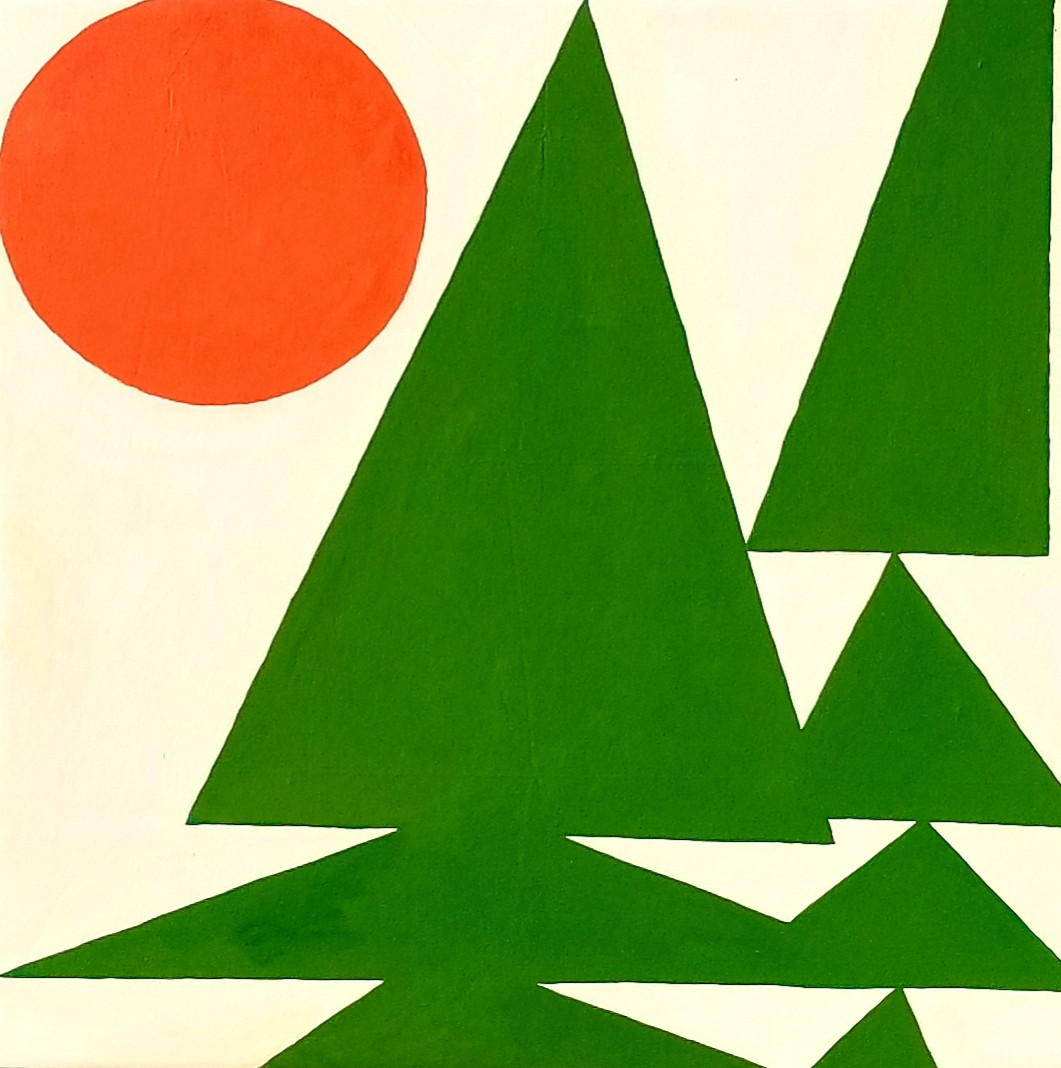

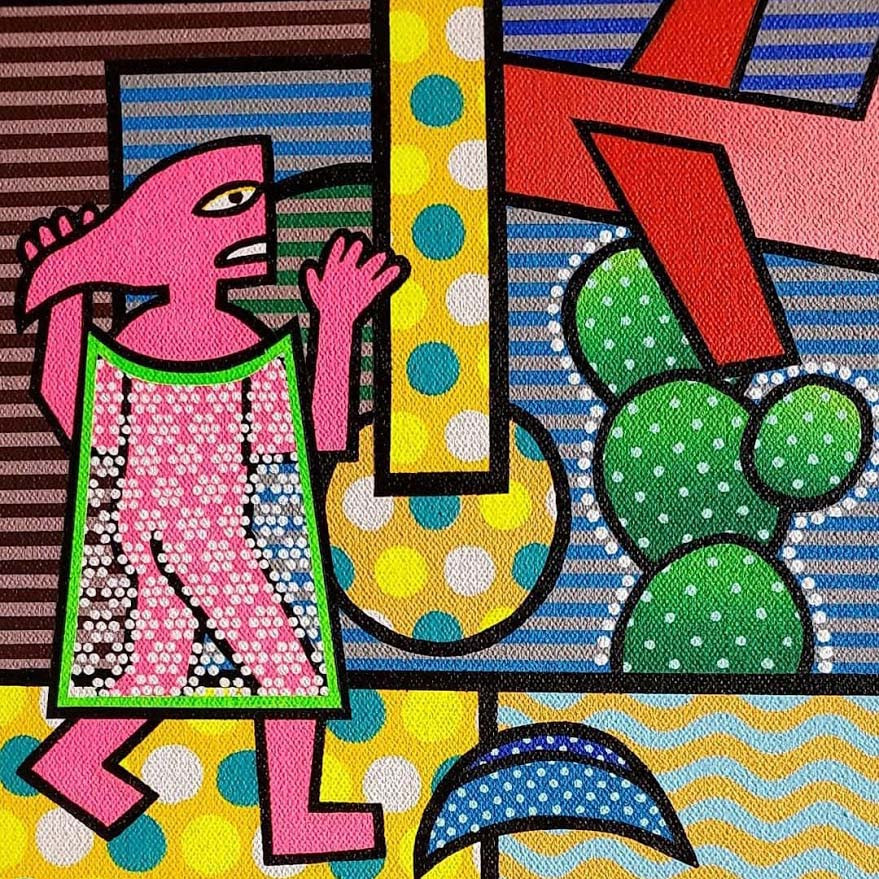

Guzzo Pinc

Painting & Drawing, MFA ’20

EGGS

Churches would be a lot more fun if priests dressed up like clowns. “Brother and Sisters, a much loved member of our congregation passed away in his sleep last Wednesday… Larry was a good father to his three children… but if you knew what that son of a bitch told me in confession there’s no way he’s going to heaven har-har-har… !” Every church sermon should be about half standup comedy.

Speaking of comedy—as I write this statement a pandemic virus is sweeping across the lands. Also, I took a food studies class and our teacher said that the international food system is definitely going to collapse… soon. Plus, this country, The United States of America, has been overthrown by a hateful band of militant pro-wrestlers. Those sad facts are just the tip of the iceberg, unfortunately. There seems to be a strong negative feeling in the air—literally and figuratively.

So why even make paintings at all? Just because things aren’t going exactly as planned—that doesn’t mean we should stop doing the things that make life worth living. Getting together with friends. Having a good time. Sharing what we love. That’s what I see this art show as… it’s a condensed version of what I love and all the good things I’ve discovered over the past few years—shared with friends and filled with about half standup comedy.

The main theme that concerns me is Time. How things change and one thing becomes another. The cycles of life and death, the seasons, day becoming night and night becoming day. This all sounds very pretentious, I know, but I think we all wonder about Time. It surrounds us like an ocean. We live in it, become what we are in it… pass away into it.

When I paint, I just paint. I am not investigating anything per se. I am not sure why I like to paint so much. Probably because I like to create. My paintings are in constant flux. The style I work in is change itself. My paintings become. When we create things we affirm our place in time. When we transform our materials and shape them with our loves and dreams we bring forth into the world something new. That is a miracle. It is the stuff religions are made of. It is true divinity. Science is the study of how materials and forces transform within Time. It is a reverence for what is. Art is an assertion and re-affirmation that we are. That we exist and are a part of time.

Everybody creates. Accountants are just more subtle than artists who have to spell it all out. Artists make creation explicit—like priests reminding us to be grateful for what we have. It is quite amazing that we even can be grateful, that we are even alive! We could just as easily have never lived at all…

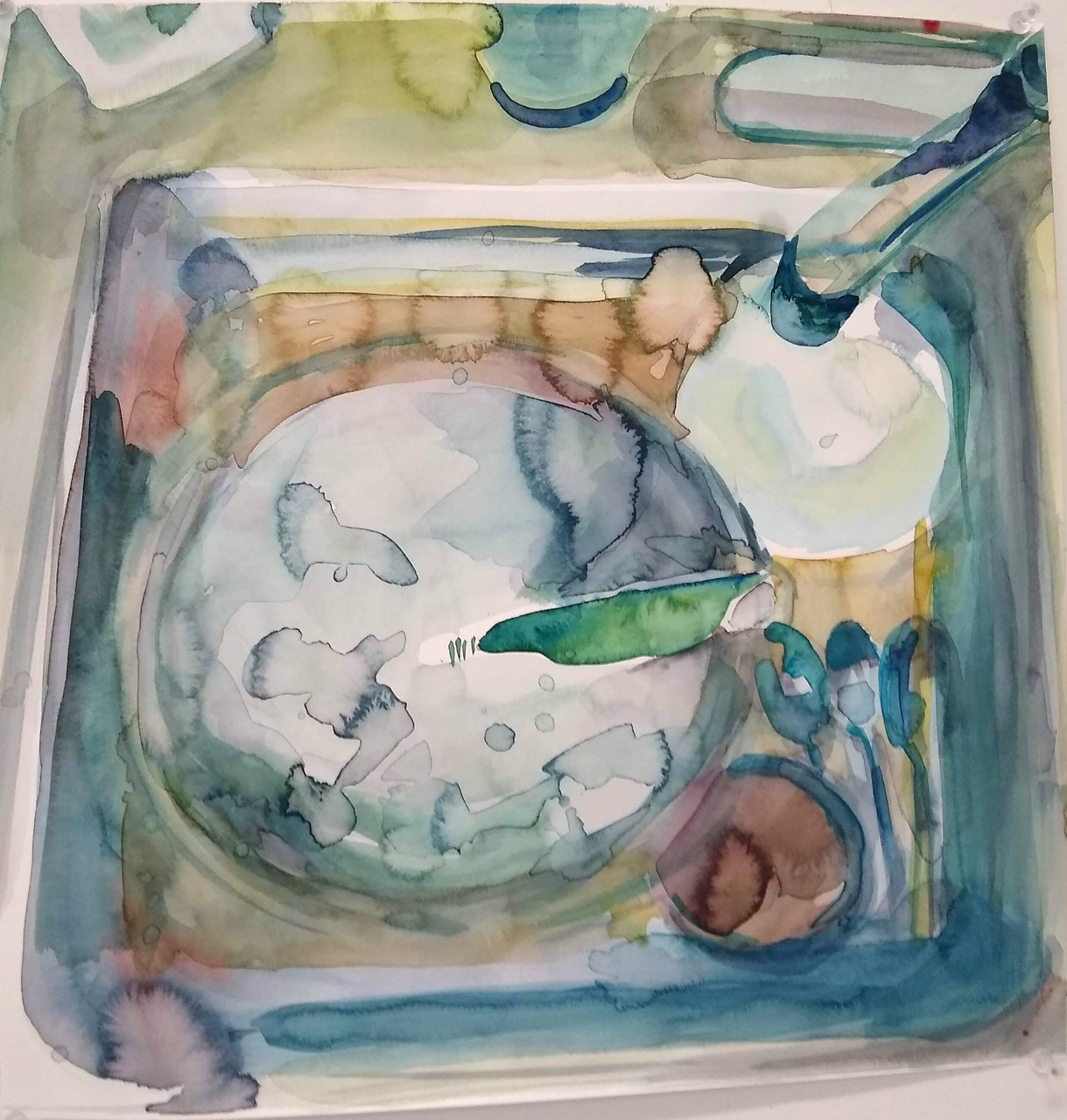

Pranav Sood

Painting & Drawing, MFA ’20

Life Is About Love & Love Is Complicated

In continuation of yet another sumptuous optical expression, the artist’s unconscious psychosocial experience is depicted here in themes of his expanded development of empathy, emotional turmoil and turbulence and new challenges faced within the expansive dimensions of maintaining a durable international love relationship. This series was the product of his unconscious exploration necessary in forming a deeper commitment to another, his practice of understanding his emerging emotions and clearing them together in the formation of a deeper, stronger love.

Works are exemplative of his emotional processing in relationship within the societal context of secretive public engagement and the silent suspicion felt, the emotional intelligence developed in a deeper understanding of his love’s challenge in contending with profound distance, and how fear can be an invitation for our courage to move us into a deeper maturation of love. Sood’s three works, “I Know What She Wants, I Want You Back Soon, and ‘The Day Without You” is the depiction of his process of evolution of both mind and heart.

Using a horizontal presentation on canvas with a more subtle vertical depiction of forms, allows his experiential depictions to be divided into chapters with auxiliary stories to enhance and more accurately depict the complexity of a single experience. This new sense of multiplicity creates individual paintings within a painting; compartmentalized in a cubist way that tells a fuller story within a deeper theme by creating various windows into the spaces of the emotional experience.

Unavoidable is the presence and scale of his tryptic, ‘The Day Without You’, completed in an impressive 5 feet by 12 feet. The starting point for this work was his complete trust of his unconscious to present and develop both line and story and moving through a progression of newly developed production efficiencies and completed with a newly achieved pace. It is here that we find the maturation of the artist in his capacity to let go and trust and to simply allow. This brought new energy, ease, and enjoyment into the production of his two smaller works having worked through the turmoil and intensity of this year’s masterpiece.

Staying true to past use of playful color and imagery, this series is a wider exploration of these principles. Tucked within these stories are visual depictions of cultural idioms, sexuality, metaphors, and Animalia. In commitment to expanded possibilities of color and its optical potentials, the use of muted hues was utilized as a means of enhancing and electrifying the vivid and bright; opening new understandings into expanded intentional use of color. Additionally, new applications of gradation were explored; both direct and indirect, as a means of defining space and optical perceptions. All this with the conscious intention of creating paintings with lasting potential for the viewer to luxuriate in the progression of new discoveries for years to come.

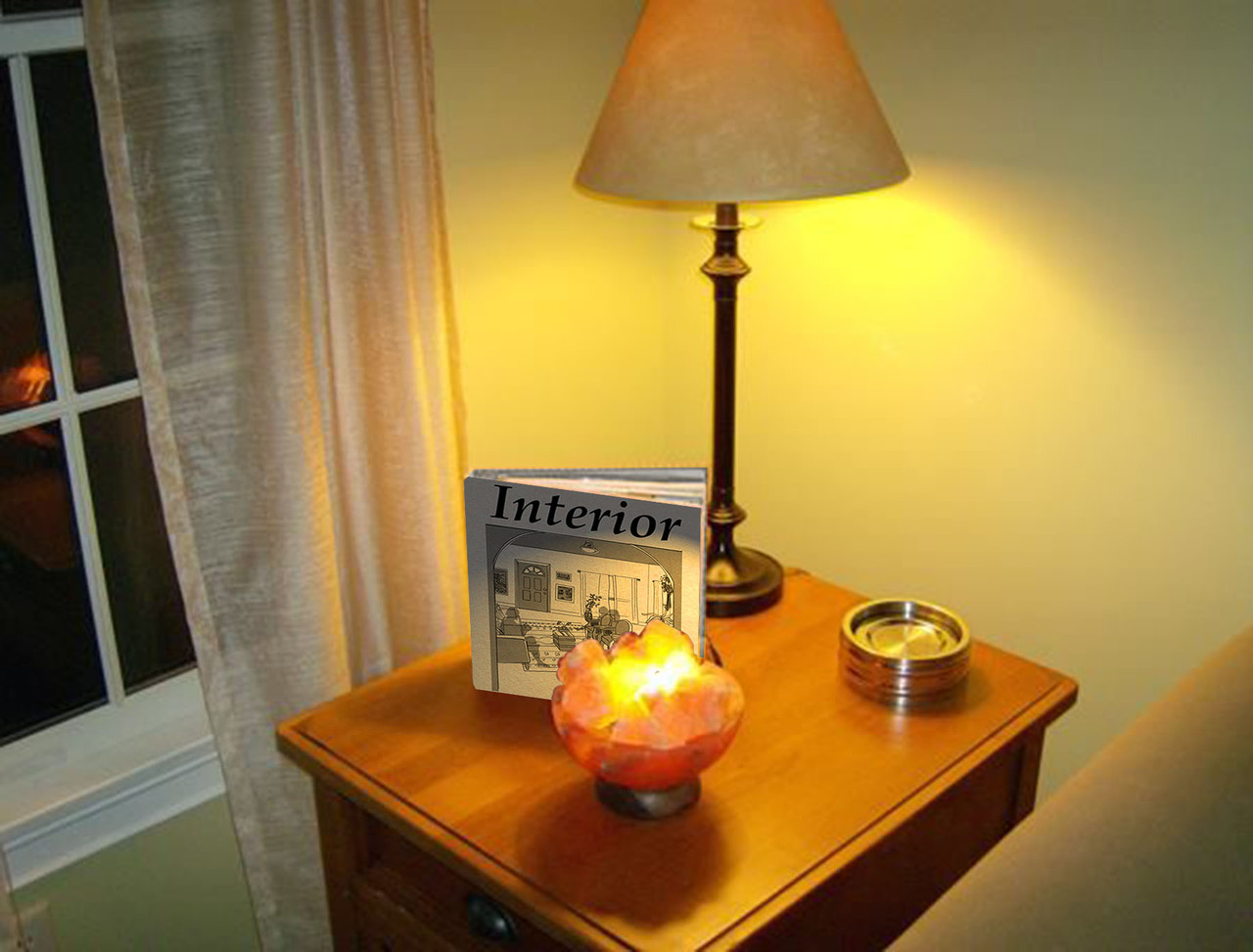

Abrahm Guthrie

Painting & Drawing, MFA ’20

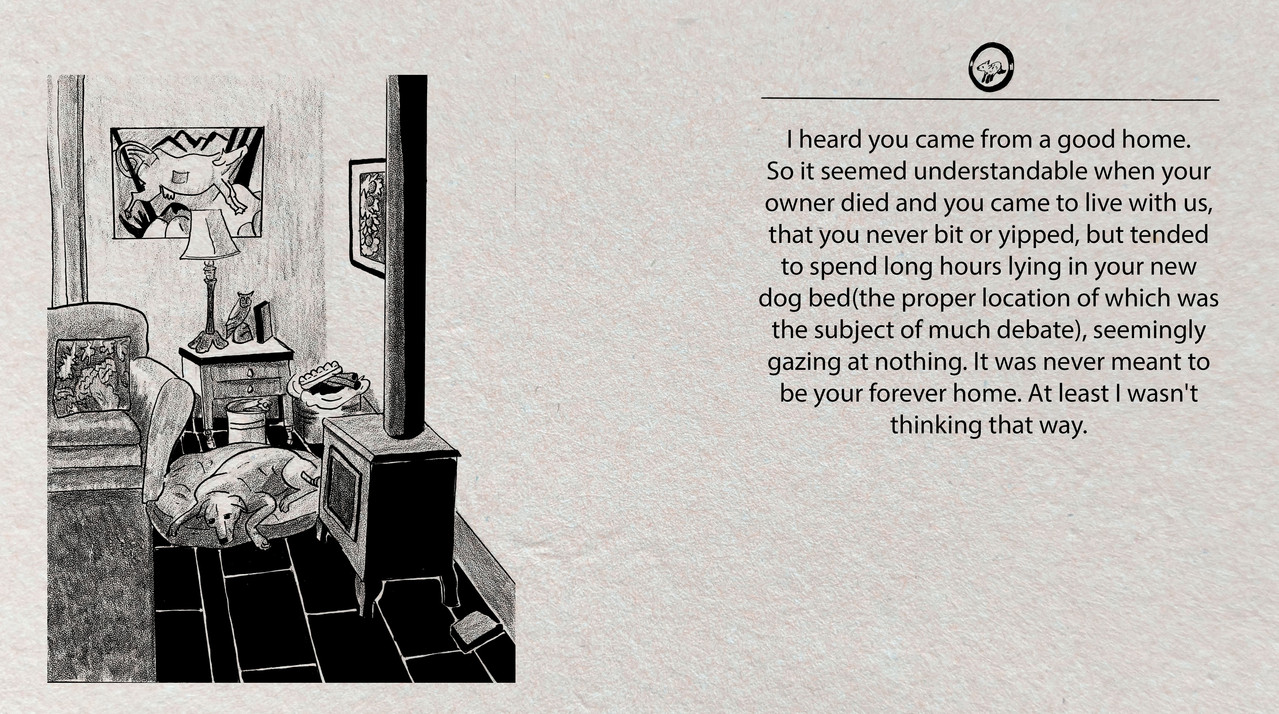

Interior

I wonder, is there a house you really feel at home in? I have never felt truly at home in any house. Just as I have never felt truly at home in my body. Homes are built and torn down and rebuilt. My home bows and creaks with the wind, my home claims memories, my home claims dreams.

Ten years ago I read Carl Jung’s book Man and his symbols, in his book he describes a dream he had about a house. In the dream his house became both home, a manifestation of his psyche and a key to deeper levels of understanding his ancestral psychology. He wrote ”The ground floor stood for the first level of the unconscious. The deeper I went, the more alien and the darker the scene came. In the cave, I discovered remains of a primitive culture, that is, the world of the primitive man within myself–a world which can scarcely be reached or illuminated by consciousness. The primitive psyche of man borders on the life of the animal soul, just as the caves of prehistoric times were usually inhabited by animals before men laid claim to them.” In Jungian Psychology the house is a symbol of the structure of the psyche or psychology, and amongst the most primal of our collective symbols. This work is a retelling of interior spaces as they are remembered and re-lived. Each painting is doggedly collaged together using memory, photo reference, and considerable fabrication. These works are glimpses of a time or points of time coming together, they are new narrative creations about the people, stories and objects in my life. They are a way to simultaneously reimagine the past and ponder the future.

Before I was born my grandparents bought eighteen acres of farmland in rural Oregon. When my father returned home from the Coast Guard my grandfather hired him to tear down the farmhouse with the expectations of a new home. My father renovated the nut dryer to have a place to live while tearing down the old place. The new house was never built, but my father continued to live on the farm in the nut dryer. He was living there when he met my mother, who soon moved in with her two children from previous relationships. If the house wasn’t cramped enough at that point, they had two more kids, my sister and I. The house was too small for six of us, so one day my mother took a sledgehammer to the upstairs. The house was in a constant state of destruction and rehabilitation. The state of the house became a manifestation of my family, barely held together by love and my mother’s hand knit sweaters. And then it broke.

My memories from that time are not only of a family falling apart. They are largely made up of the house itself: the way the stairs creek, the sound of the old chimney bulging with heat, the light trickling in from dusty windows, absorbed into the dull, splintered, wood floor. These memories are joyous, a celebration of the bodily world, brimming with activity.

After my mother left, my father spent twenty years of his life restoring old and broken homes for the elderly, disabled and low income people. They were mostly mobile homes, all descending rapidly into the earth. His inability to keep his home from falling apart left him in disrepair. I wonder if all his later actions were to repair that rift. Was there something deep in his bones that drove him to pick up his tools every day? In the same way that my father picked up his tools every day and set to work, I cultivate and rebuild with the tools at my disposal: handmade paper, scissors, paint. Though I have never truly felt at home, I feel a deep affinity for each home I’ve inhabited. I imagine every one could be found in my psyche. I try to portray them, to tell their stories, in a way that feels like exorcising the ghosts of haunted houses.

Lucas Pointon

Metals, MFA ’20

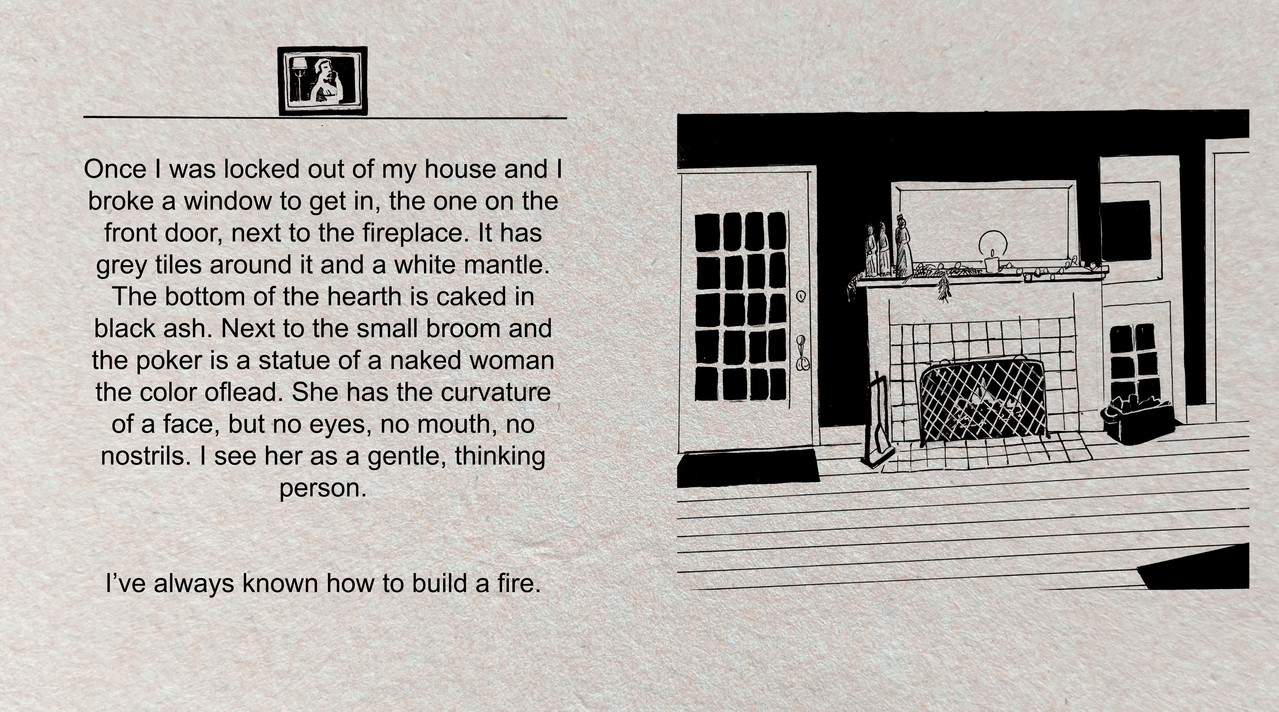

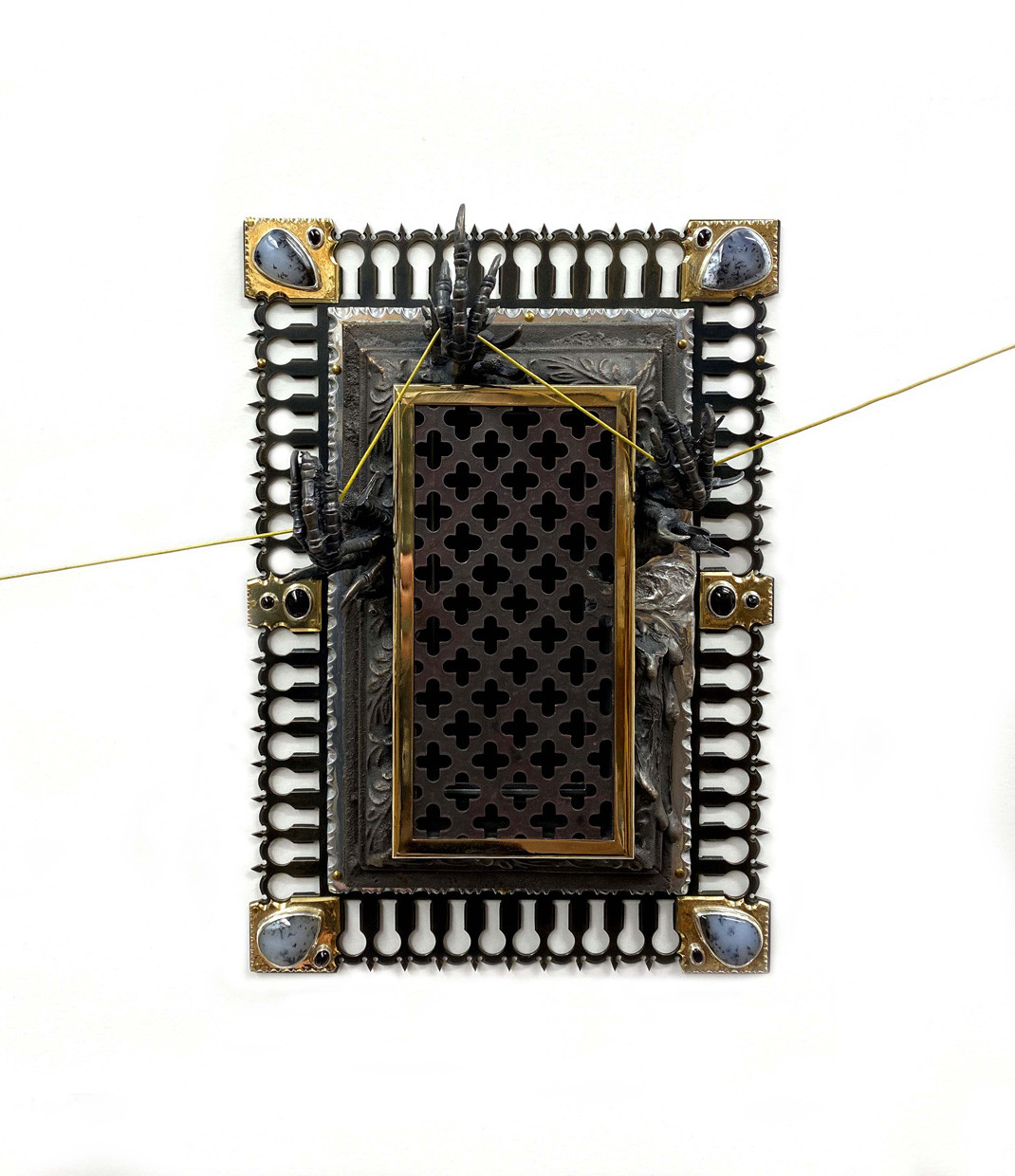

de natura rerum – (or) on the nature of things

My work explores issues of life and death, and issues related to my deep personal engagement with the natural world, including landscape and wildlife. Many of my pieces formally reference medieval reliquaries, which are elaborate and precious metal containers that hold the relic of a saint, such as a bone fragment. Reliquaries provide a visceral religious experience, melding life and death into one mysterious indivisible whole. Reliquaries represent an attitude towards death that is interesting to me, and a belief in the cycles of life and death as part of the process of renewal and veneration. I have utilized this format as a way to explore the spiritual connection I feel towards the outdoors and my participation within it. The act of making a reliquary, with the precise and time-consuming processes of the metalsmith, allows me to honor and elevate my practices of hunting and fishing, and to serve as a reminder of the moral compass that informs these activities.

I am both an artist and an avid outdoorsman and my artworks memorialize my appreciation for those outdoor activities. I hunt with a bow that I have made. Above the handle on the bow there lies a painted banner inscribed with the phrase “such as we are you shall be”–a medieval statement that refers to the inevitability of death, both for the hunted and the hunter. The phrase faces me as I hold the bow, aiming, and reminds me to focus on the responsibility of taking a life. This transcendental exchange is important to me, and has served as an ethical marker that informs other areas of my life. I become part of the greater cycles of life and death, and I understand my role within the natural world.

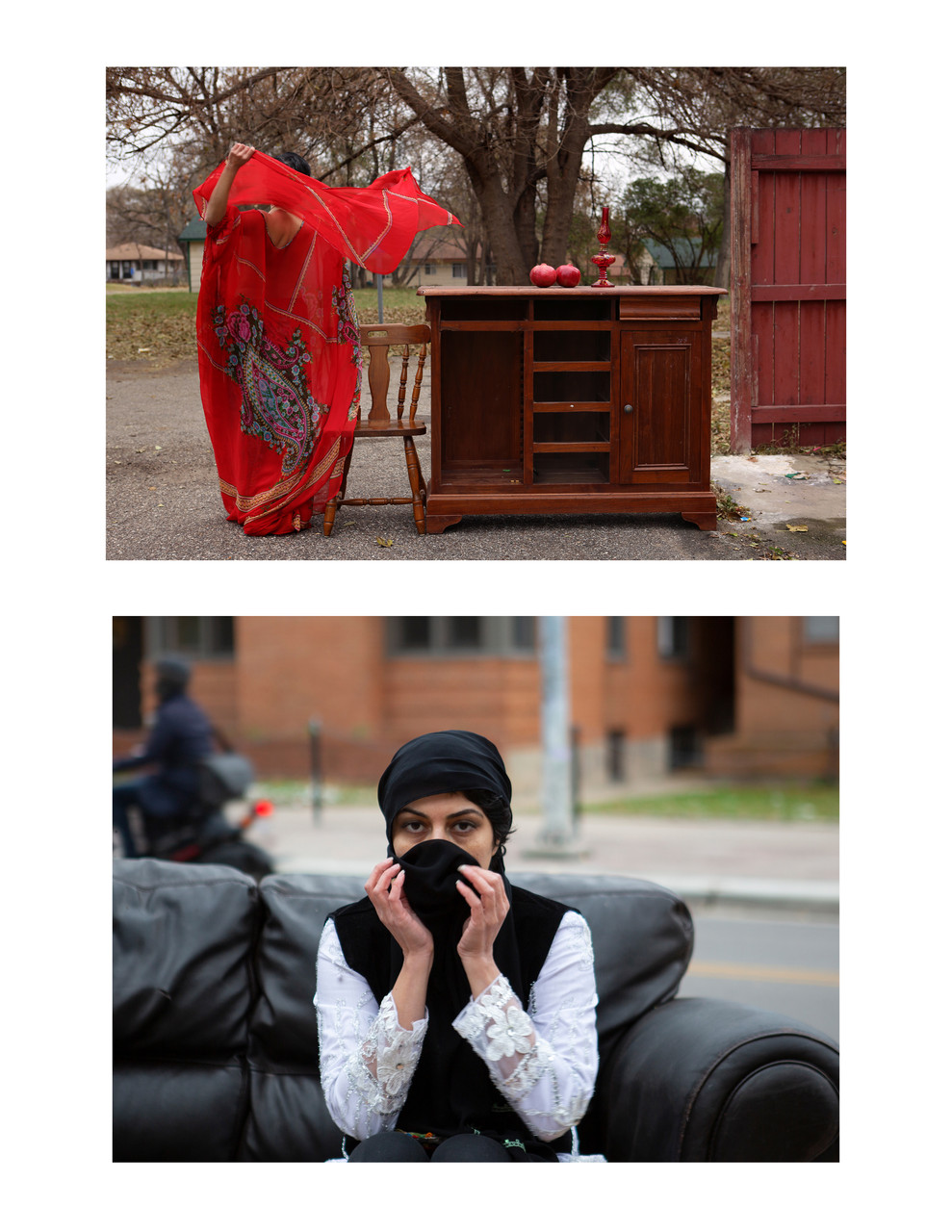

Maryam Ladoni

Photography, MFA ’20

Cheltikeh

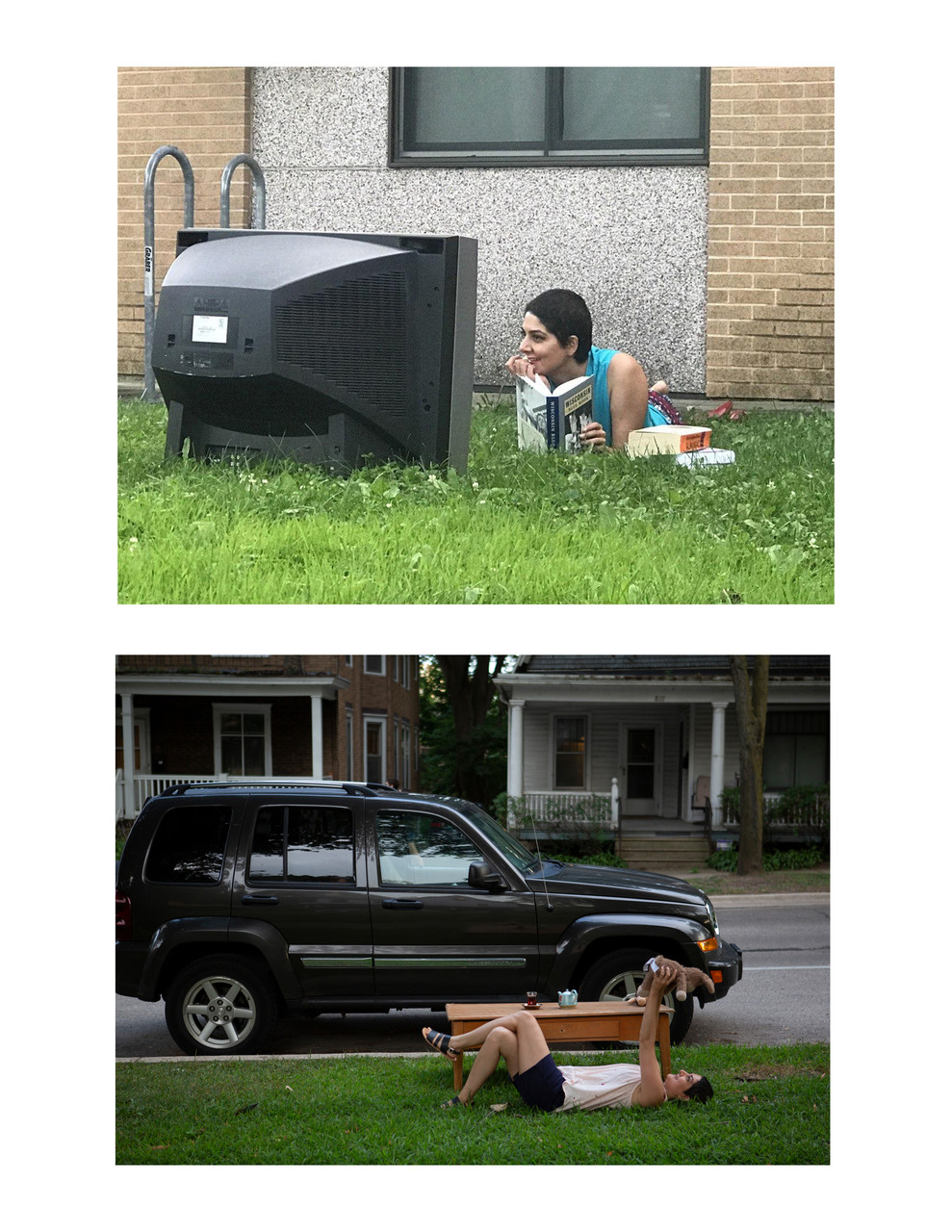

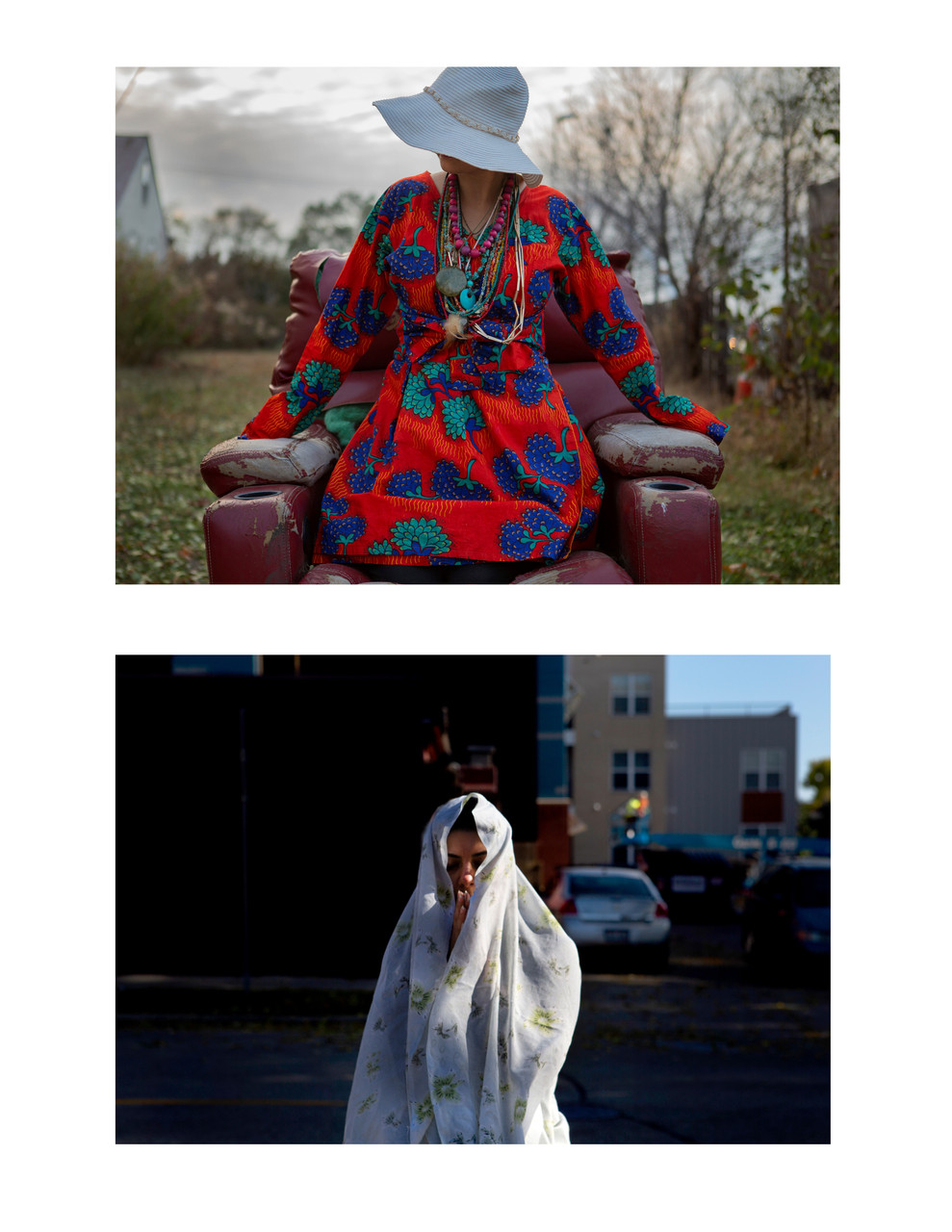

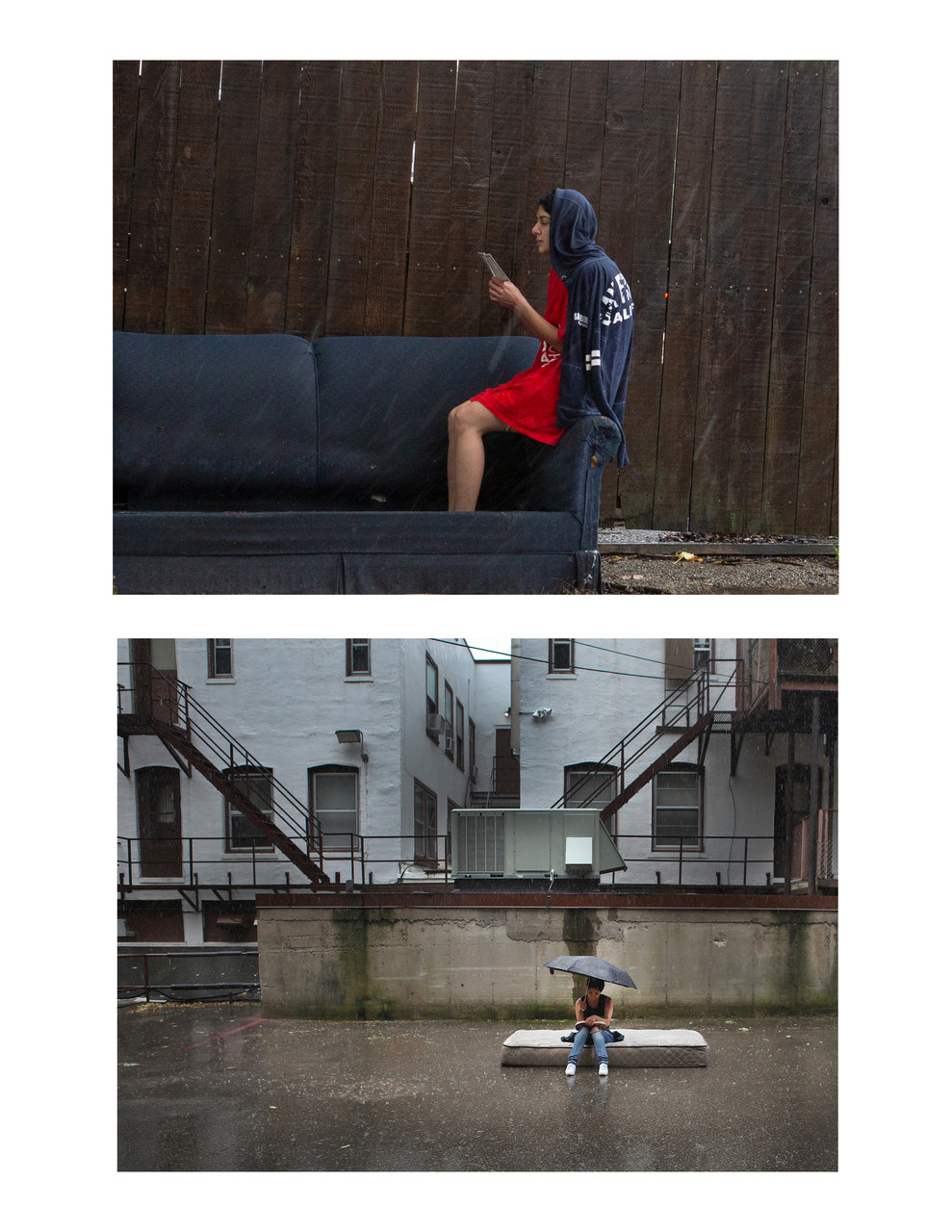

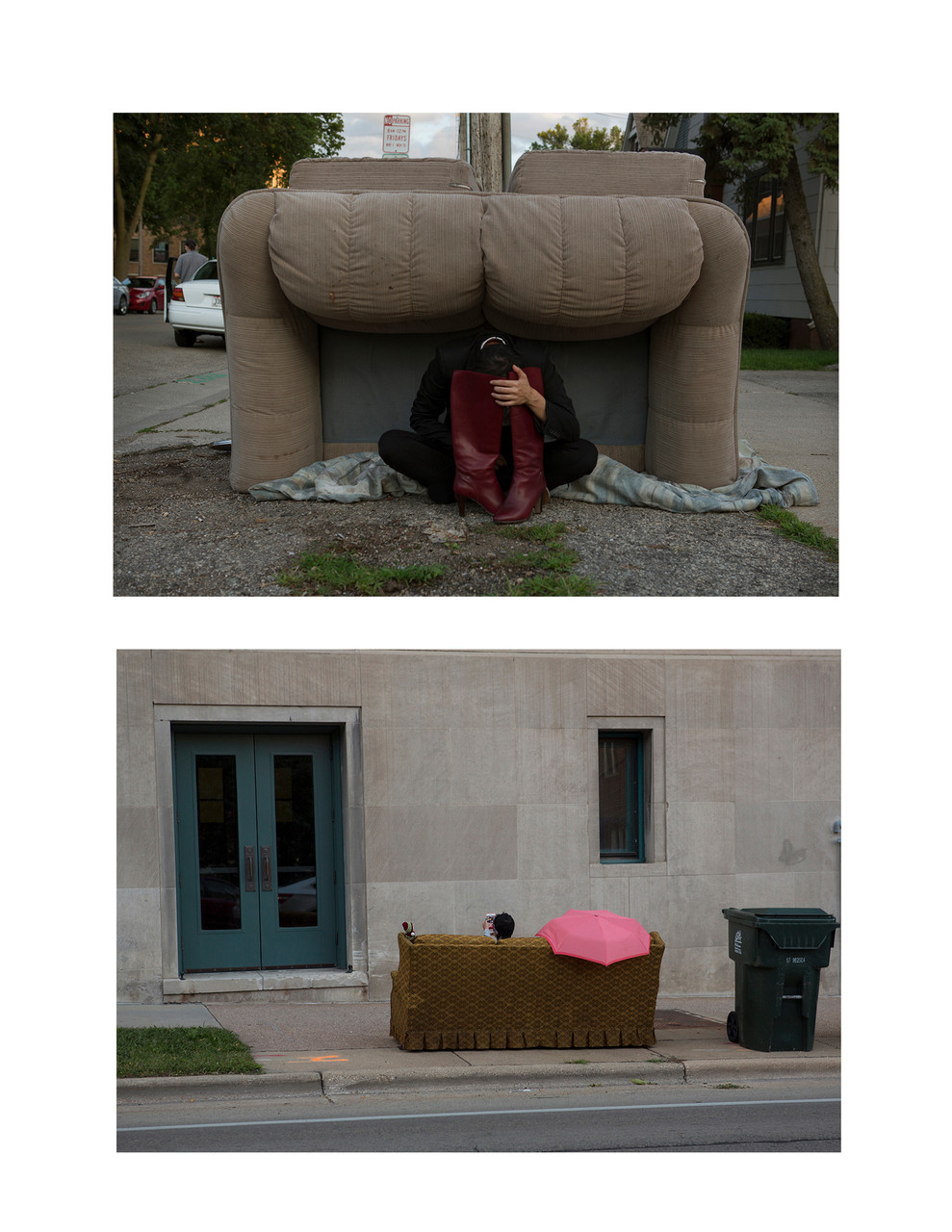

My camera, which ironically this time is not in my hands, explores a multitude of answers in “Cheltikeh.” The word means 40 pieces in Persian. It conceptually means infinity and the word for quilt as I see my life as a quilt of experiences.

My marriage ended in the winter of 2016, and immediately after I moved to the United States to pursue my art. As a result of these significant changes, I walked in the streets alone and deepened my understanding of my identity, my culture, and all of my past relationships. I analyzed my experience living in the US and the new layer it has added to my life. As an Iranian far from home, I experienced the emotional effects of time difference, physical distance and political conflicts. Sometimes, I shared my feelings with friends and heard their experience as well. Then I borrowed their cloths or what meant to them as home or identity.

Besides, while walking in the streets I found much abandoned furniture on sidewalks and roads. They did not belong to the streets and had a temporary and unbalanced presence which resembled a similarity to my place in the world. Using the elements/fabrics, I acted as if I was in my home and asked my friends to photograph me with those abandoned objects. Not all of them were photographers or artists but sharing my stories helped them to understand the performance.

I do not know where my home is, and no physical wall or boundary can define my sense of home. Most times rather than being responsive I am questioning what has made me or is important for me. My goal for Cheltikeh is to represent all of this complexity through collaboration with a diverse group of friends who have the same experience of living far from home and watch the layers of my identity unfurl through their perspective.

Kayla Story

Photography, MFA ’20

Familiar Words Between Good and Bad

Only one photograph exists of my father and I, him 26 and grinning, me a few months into this world, dressed in pink and balanced on his knee. He left without a trace shortly after, not even bothering to pay child support until I was almost 13. This photograph has some how stayed with me for decades, at once an object tangible and present in my life but in the same breath embodying what was entirely absent. It wasn’t until I was 30 that I looked him up with the intent of potentially reaching out, and the decision to address the part of me that was this father shaped impression. However, I was confronted with images of a happy family that had no knowledge of my existence, or of his role as my absent father, and my feelings about his unwillingness to see me as a human, took on a new more complicated state of being.

Familiar Words Between Good and Bad is a collection of works looking into the void of fatherlessness and searching for the subtle realities of what is left behind, examining presence as it crosses paths with absence. There is a pervasive narrative surrounding a perfect family life, one that is deeply intrenched in cultural conventions. A singular idea of a successful life is weighted against crippling apprehension of failure, and a public varnish is put up to obscure the view of private difficulties. It is no wonder then that being open about realities found within families can often feel like an unthinkable breach.

Some works are deeply personal and some draw directly from conversations with 32 adults who experienced, and have had to come to terms with having, an absent father as I did. One connection for every year I have spent without a father. In many ways the work aims to push at the barriers of talking about grief, loss, legacy, and complicated love. Opening up a conversation about the indelible feelings surrounding the people who raise us, or who choose not to. Extending a conversation about family beyond the binary of having something being automatically good and not having as simply bad; Fatherlessness is never simple.