The UW–Madison Art Department is a national leader in the cultivation and production of creative expression and the visual arts. Our undergraduate and graduate degree programs set the practical, critical-thinking and collaborative foundation for students to excel in any area of artistic focus: painting, printmaking, graphic design, sculpture, ceramics, metalsmithing, glass, furniture-making, papermaking, photography, digital media, video, performance and more.

For more than a century, we’ve set the standard for arts learning: we established the first glass-blowing lab in the country, our printmaking programs are consistently ranked the best in the country, and we’re home to internationally acclaimed faculty members and visiting artists. Many icons in the industry have been inspired in these very halls – from designer Iris Apfel, to glass sculptor Dale Chihuly, to performer Linda Montano.

Degree Offerings

B.S., B.F.A., M.A., & M.F.A. in Studio Art

B.S. in Art Education

Undergraduate Certificate in Art Studio or Graphic Design

Mission Statement

We see Art and Design as a vital, fundamental force capable of conveying images and ideas across time and place with the power to address all human concerns.

As artists and designers, we recognize our place in a historic continuum of learning and teaching in which students play a critical role.

Our mission is to cultivate, strengthen, and pass this power directly to the students on whom the future of Art and Design depends.

We champion diversity, discipline, rigor and innovation and above all, freedom of expression. Our accomplished and diverse faculty work across creative disciplines to help students develop the creative, critical, and technical skills needed for life-long engagement in the visual arts.

Vision Statement

The mission of the Art Department at the University of Wisconsin-Madison is to educate students in studio art and design in order to form lasting contributions to knowledge and culture. Our mission mirrors the guiding principles of the university whose outreach efforts influence lives within the classroom, the state of Wisconsin, and beyond.

Seated within the School of Education, the Art Department curriculum allows students to join their academic and studio disciplines in order to source the full potential of the University. Research offerings at the University of Wisconsin are ranked among the highest in the world including our libraries, museums, laboratories, historic collections, faculty, staff, and visiting scholars. Student learning and curriculum is also supported on campus by the Chazen Museum of Art, Tandem Press, and the Division of the Arts. Our prominent and diverse faculty work across creative disciplines to teach hands on skills, critical thinking, observation, and innovation.

Art students are presented with an interdisciplinary, professional practice, and standards for scholarship in order to develop creativity, meaning, and social engagement in the visual arts. The mission of the Art Department values the diverse contributions, background, and experiences of each student who serves as a catalyst for the extraordinary within the contemporary practice of art at University of Wisconsin-Madison and the world.

DEPARTMENT HISTORY

Opened in 1877 on the same spot where the current Science Hall now stands, the Old Science Hall included laboratories, lecture halls, department offices, and museum space. The building caught fire in 1884 and was completely gutted.

A combination of spirit and social dynamics has given the state of Wisconsin and the University their distinctive identity and character. Some of this is readily traceable to life on the frontier during the state’s formative years. Life was arduous and understandably simple. The circumstances did not encourage any immediate flowering of the visual arts. The early settlers regarded art as education—art as something to learn how to do or as a desirable enterprise for improving self-expression and evidencing qualities of gentility, especially among women. In spite of the more pragmatic concerns of frontier life, the University showed a comparatively early interest in fine art. When the Science Hall, the university’s first major building constructed since the Civil War, opened in 1877, it contained an art museum. Unfortunately, in 1884 the gallery and the collection were lost when the building caught fire and its contents were destroyed.

Early courses in Latin touched on classical art and the UW Extension offered art survey and art appreciation courses, but, as an academic discipline, art at the University of Wisconsin–Madison grew out of engineering. In 1910, the College of Letters and Science initiated a manual arts curriculum, offering industrially-oriented subjects such as mechanical drawing, woodworking, and metalcraft designed for students hoping to secure positions as directors and supervisors of manual arts and vocational work in public school systems. Additional courses embraced the more traditional freehand drawing and perspective, watercolor rendering, and pottery.

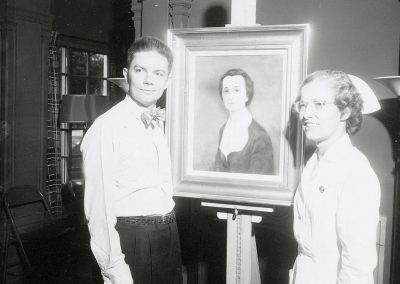

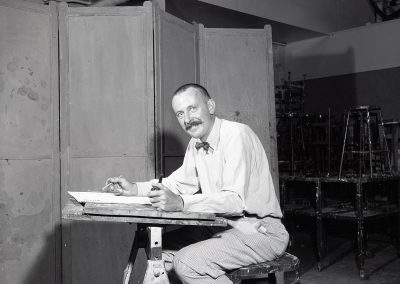

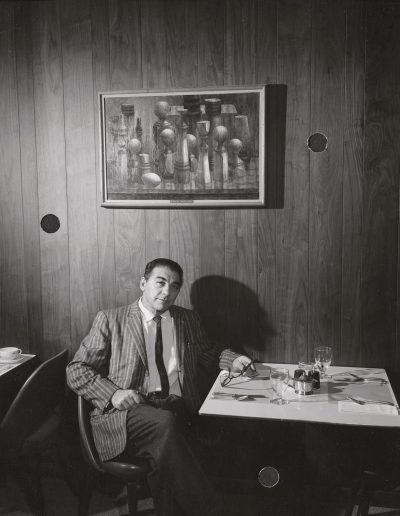

Portrait of William Varnum, Professor of Art from 1912 to 1946.

By the mid-1920s, the program had expanded into a department of industrial education and applied arts. Though the curriculum emphasized vocational training, it also offered courses in drawing, painting, design, crafts, and primary arts for teachers.

In the 1930s, the newly established School of Education began separating from its original home in the College of Letters and Science, including a department of art education, though the focus remained on the use of artistic principles in the creation of industrial materials. William Varnum, a design educator and member of the art faculty for more than twenty years, served as chair of the department.

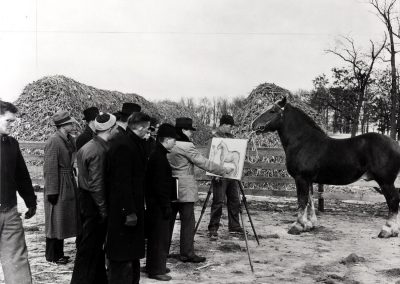

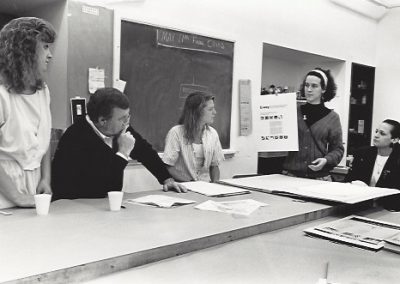

Professor James Schwalbach looks at drawings from the WHA Radio program “Let’s Draw.”

As the department continued to evolve, its vocational emphasis gave way to a program designed to familiarize the student with basic and advanced art practice, leading to the development of teachers and supervisors of art (drawing, painting, design, commercial and professional art, and the art crafts) in public and private schools, teachers’ colleges, and universities. The curriculum did include an additional accommodation for students not majoring in art education but who were interested in appreciative or professional knowledge of art theory and practice through studio participation as well.

By the end of the 1930s, the department offered a baccalaureate degree in applied art. Art education continued to be the department’s major emphasis through the 1930s and into the early 1940s, training teachers to staff high school programs around the state.

A generation of Wisconsin schoolchildren also took art lessons from the radio, specifically Professor James Schwalbach’s award-winning weekly series “Let’s Draw,” which pioneered on-air lessons at the Wisconsin School of the Air broadcast Station WHA from 1936 to 1970. Professor Schwalbach narrated the program for fifteen years under his philosophy that art should be a daily source of enjoyment for all, and not just a privilege of a talented few individuals.

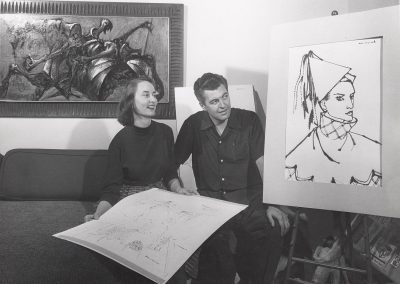

Professor Fred Logan.

Change does not usually happen rapidly in an academic setting, but for Fred Logan, a relatively new member of the art education faculty, the world turned topsy-turvy as far as education was concerned in 1946. Veterans returning from service in World War II, were eager to pursue their education through grants provided by the G.I. Bill. University enrollment swelled in all areas of the campus. The surge placed unprecedented demands on the University’s physical and human resources. Art was no exception. Those students who came to study were more mature and demanding than those of previous generations. They were in a hurry to finish their education and get on with their lives. And so, following World War II, the department balance shifted toward applied art. New faculty appointments indicated a trend, arriving with established records as artists with marginal academic credentials, which grew and eventually matured in the postwar years.

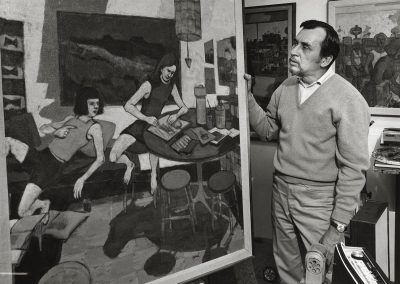

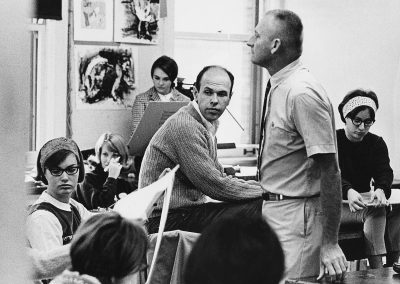

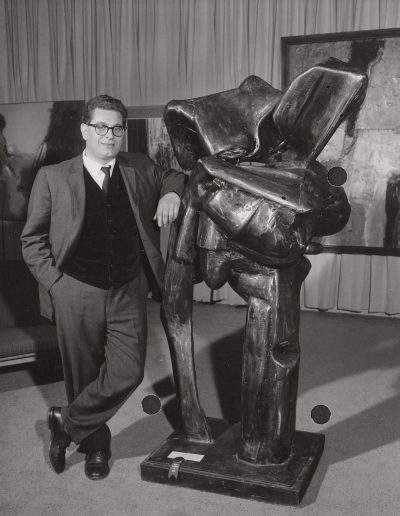

Professor Alfred Sessler (center) and Professor Robert Grilley of the Art Education Department with works for the 2nd Annual Summer Session Art Exhibition at the Memorial Union.

Alfred Sessler was a recent graduate student who had worked on federally sponsored Public Work for Arts programs during the Depression. Similarly, Arthur Vierthaler, who had considerable art metal experience but no formal training in art education, taught metal, design, and drawing, following the passing of William Varnum in the summer of 1946. Shortly thereafter, Dean Meeker, a graduate of the Art Institute of Chicago, arrived to teach courses in drawing and painting. These appointments were followed by a wave of new faces, including Santos Zingale, John Wilde, Warrington Colescott, Donald Anderson, and Gibson Byrd. The presence of women on the art education faculty, begun earlier with the appointments of Della Wilson and Helen Annen, continued with Marjorie Kreilick.

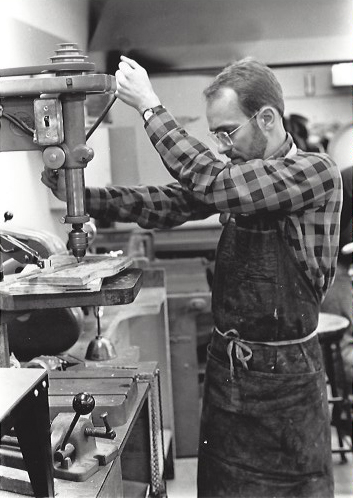

Art Professors Robert Grilley, Helen Annen, and Dean Meeker in the studio, 1952.

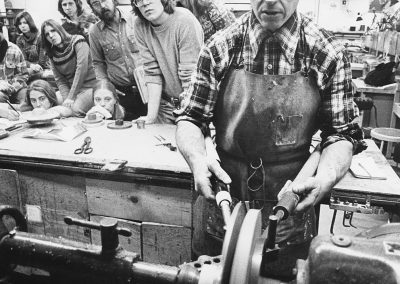

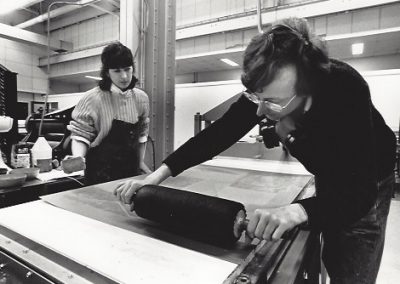

The new faculty selected to staff the postwar program were predominantly de facto artists-in-residence, bringing restless energy, creativity, and innovation. Dean Meeker, for example, offered the first college course in serigraphy. Greater demand for these studio courses meant increased enrollment and building a highly visible, quality program garnered increased prestige. During his thirty-seven years of teaching printmaking from 1949 to 1986, Warrington Colescott established a notable studio in intaglio printmaking and was one of the innovators in advancing technique and print culture at Madison.

Dean John Guy Fowlkes.

The School of Education Dean John Guy Fowlkes made sure the administrative environment was right to capitalize on the momentum. Fred Logan helped establish the basis for a relatively smooth transition of emphasis from teaching art educators to cultivating the talents of potential studio artists. Although primarily an art educator, Logan recognized that the future of art at Wisconsin—and in the profession—would be in studio programs. The 1950s brought a broad and substantial expansion of the program. At the middle of the decade, the department conducted a self-assessment showing that from 1945 to 1955, the Department more than tripled its capacity to deal with the enormously increased demands both from regular art majors and others requiring special art courses in their curriculum. During that same period the staff grew from six to eighteen, representing great diversity and breadth of experience.

Students sit on the steps of the Education building.

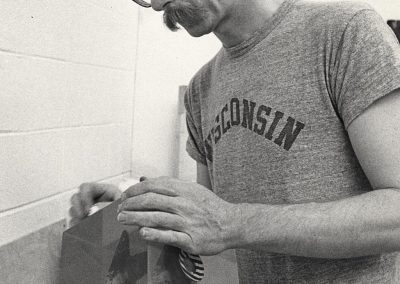

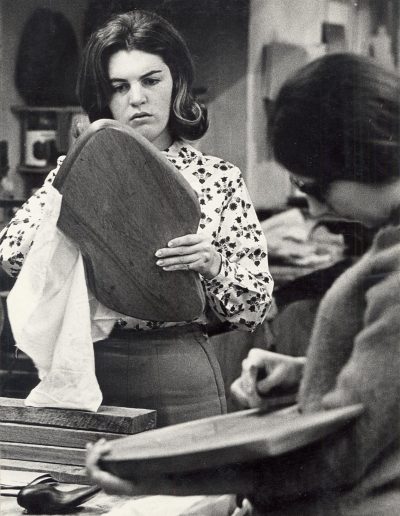

A substantial remodeling of space in the Education Building to accommodate the growing program proved to be a major boost for the department during the 1950s and the studio activities that had been previously squeezed into the Journalism Building. The remodel produced an exhibition gallery on the main floor, a new ceramics workshop, a model art classroom for teacher training, more spacious drawing and design rooms, space for sculpture activities, enlarged art metal quarters, and expanded space and equipment for photography, lithography, serigraphy, and general crafts.

In 1957, the program further honed its reputation with the approval of a Master of Fine Arts degree. Considered the terminal degree in the field, the program offered advanced training and opportunities. In 1978, a similar program, the Bachelor of Fine Arts, was introduced to provide undergraduates better professional preparation in studio areas than offered by the existing B.S. program.

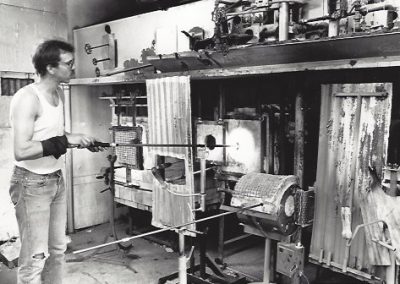

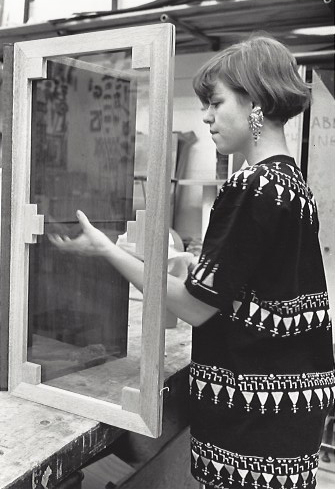

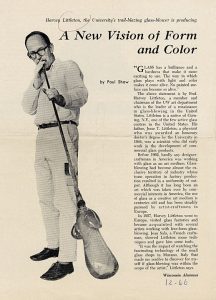

A Wisconsin Alumnus Magazine article about Harvey Littleton, a “trail-blazing glass-blower.”

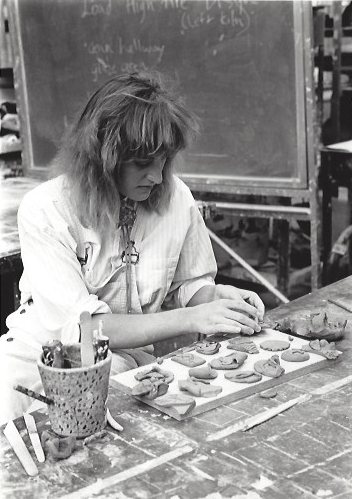

By the beginning of the 1960s, the present-day configuration of the art department program had been firmly established. The initial generation of faculty who had established the studio art program was augmented by the appointments of Raymond Gloeckler in art education and relief printing, Jack Damer in lithography, and Walter Hamady, Phil Hamilton, William Weege, and Cavalierre Ketchum in graphic arts and photography. Harvey Littleton, who served as department chair on two separate occasions in the 1960s and early 1970s, had come in 1951 to teach ceramics but soon became intrigued by what he perceived as the neglect of blown glass as an art form. Following research in Europe and a major workshop at the Toledo Museum of Art, Littleton launched the first studio hot-glass program at an American university in 1962. From Littleton’s Verona studio, the program grew to encompass names and personalities that would redefine the art glass movement worldwide. Early students included luminaries such as Fritz Dreisbach, Tom McGlauchlin, Sam Herman, Marvin Lipofsky, Christopher Ries, and Michael Taylor. The program’s best-known alumnus is arguably Dale Chihuly, whose Mendota Wall can be seen on the main level of the Kohl Center. Similarly, Don Reitz gave new impetus to the ceramics program, while Hamady stimulated developments in the book arts and papermaking.

An aerial view of the completed George L. Mosse Humanities Building in 1970.

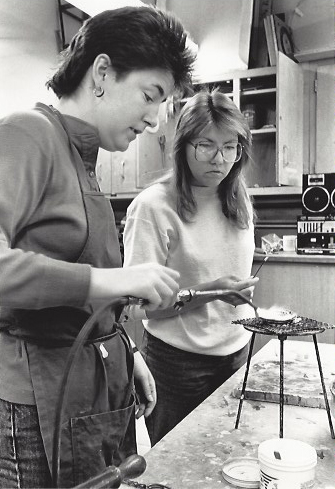

These developments were tempered by more practical concerns, however. By the end of the 1950s, the increased growth of the program was obvious, and plans were laid to seek larger quarters and better equipment. In 1962, building committees were established in the department of art and art education, the history department, and the School of Music to prepare plans for what is now the Humanities Building, that would complement an adjacent art museum housing the department of art history and the Kohler Art Library. After many budget and design delays, the new Humanities Building, designed by Chicago architect Harry Weese in the Brutalist style, finally opened in 1969. It provided the department with administrative offices, studios, classrooms, and a small gallery. For the first time, there was enough space to offer each of the major components of the program—art education, two-dimensional studio art, three-dimensional studio art, and the graphic arts—their own separate areas. New equipment made it possible to offer instruction in state-of-the-art developments in the various media.

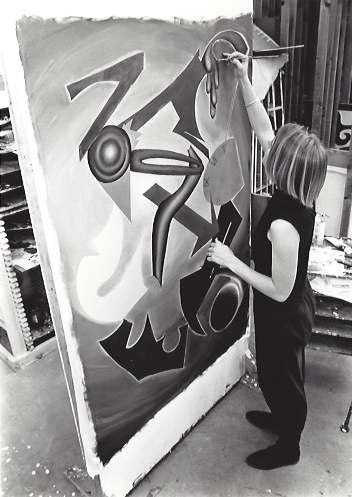

The program continued to grow, adapting to changing times. The curriculum embraced newer expansions of the concept of making art to include computer art, video, and cross-listed courses dealing with lighting, set design, and sound design as well as courses which encourage students to explore topics such as the social functions, business, and public role of art in society.

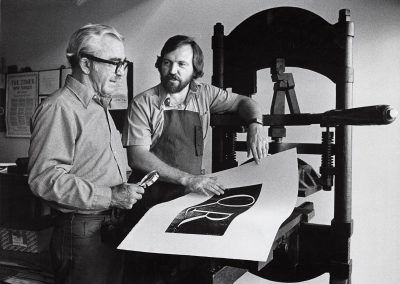

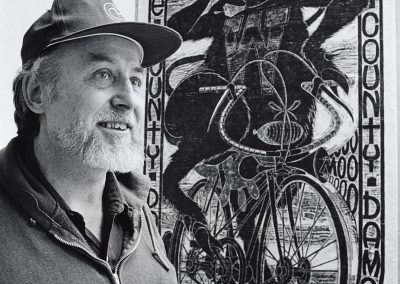

A major addition to the Art Department came in 1987 with the establishment of Tandem Press, founded by faculty member Bill Weege. Built on a long tradition of excellence in printmaking at the university, Tandem Press produces prints by nationally recognized visiting artists and offers students opportunities to learn about the artistic and economic factors that go into the operation of a major print studio.

Despite the opportunities afforded by the Humanities Building, the department found itself searching for space almost as soon as it opened. For the next four decades, nearly every dilapidated storefront along University Avenue housed a graduate studio or exhibition space, physically spreading the department across campus and the city.

A structure of red steel beams and cables form a decorative entry to the exterior of the Art Lofts building at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. The state-of-the-art facility houses teaching spaces for several fine art disciplines as well as private studio spaces for faculty and graduate students.

Relief came when the department acquired a foothold in a warehouse next to the Kohl Center with the renovation of an aged warehouse building at the far southeast edge of the campus. The $9.2 million project, completed in 2009 and dubbed the Art Lofts, united study, work, and exhibition spaces for the ceramics, glass, neon, and papermaking facilities, a bronze foundry, darkroom and digital labs, a woodshop, graduate and faculty studios, a large performance space, as well as a second gallery space.

In 2003 during Arts Night Out, visitors to the 7th Floor Gallery in the Mosse Humanities Building admire a sculpture by art graduate student Chris Walla. The untitled eight-foot tall sculpture, made of steel, wood and linoleum, was part of an exhibit of Walla’s work entitled Domestica.

From a standpoint of public perception, perhaps the most tangible testament of the department’s ongoing creative activities can be found in the multitude of weekly student exhibitions which appear in the 7th floor gallery of the Humanities Building and the Art Lofts gallery each year, and in the Art Department Quadrennial Faculty Exhibition, an event which has become a cotillion sampling recent work by current and emeritus faculty. The first comprehensive faculty exhibition was organized and presented in 1974 as joint venture of the Art Department and the Elvehjem Museum of Art (then known as the Elvehjem Art Center, now the Chazen Museum of Art) to help celebrate the university’s 125th anniversary.

In many ways, the shows represent a periodic revisiting of the frontier. It is not so much a consideration of the frontier as a landscape boundary, but more an exploration of artistic potential. That continuing exploration has become the primary mission of the Art Department.

—Adapted from Exploring Artistic Potential: An Informal History of the UW-Madison Art Department, 1999, and The Arts at Wisconsin, 2012, written by Arthur Hove, special assistant emeritus of the University of Wisconsin–Madison.